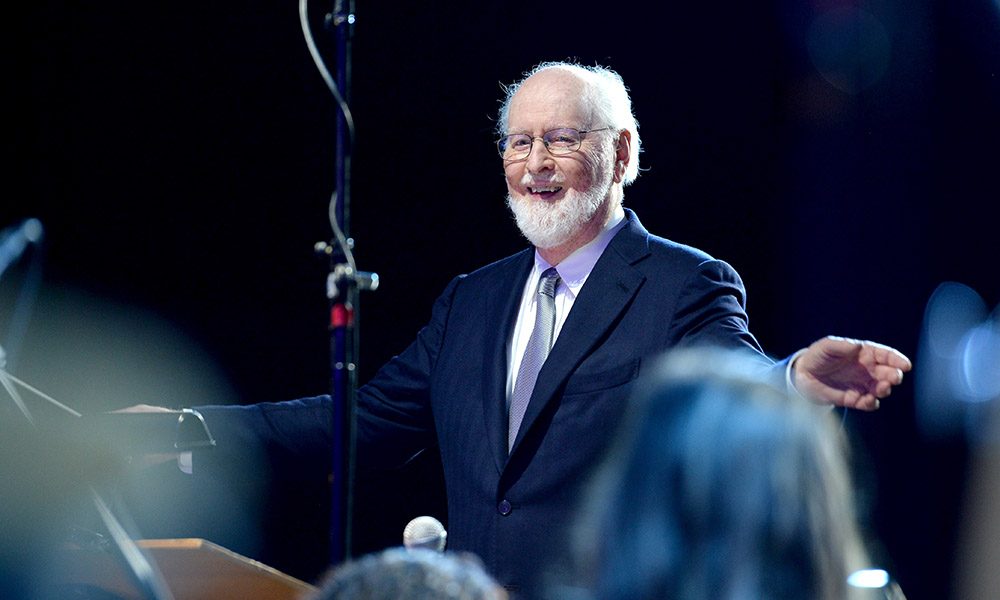

John Williams: The Force Is With Him

Multi award-winning film composer John Williams has created a stunning legacy that has changed the way soundtracks are thought of. We trace his genius.

The term “genius” is far too often, bandied about – alongside its catchall companion, “icon.” But in the case of John Williams both words apply, while barely doing justice to the magnitude of his talent.

John Williams isn’t just a soundtrack composer, he is the undisputed master of the film score. He is also a creator of contemporary classical music with a post-romantic style, and a grand conductor, pianist, and jazz buff who used to play piano for Mahalia Jackson. He remains an extraordinary force of nature in his field: his long-standing relationship with Stephen Spielberg is a given, ditto his work for George Lucas and, more recently, the ever-so-slightly popular Harry Potter movies. Williams has won multiple Academy Awards, Golden Globes, British Academy of Film and Television Awards, and Grammys. In a specialist field, his albums have sold in the multi-millions.

His recording career goes back to the 50s and encompasses concertos, orchestral and chamber works, and gospel music. To pick at random – and his discography is truly vast – his tribute to Leonard Bernstein, “For New York,” which aired in 1988, saw him conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra. American Journey (1999) is another triumph, commissioned by then-President Bill Clinton for the United States’ official millennium celebrations.

The soundtrack world is packed with great composers and memorable themes: the aforementioned Bernstein (West Side Story), Bernard Herrmann (Citizen Kane, North By Northwest, Psycho), Maurice Jarre (Doctor Zhivago), Ennio Morricone (The Dollars Trilogy, Once Upon A Time In The West, Once Upon A Time In America), and Vangelis (Blade Runner, Chariots of Fire). The list is vast, but John Williams occupies the peak with those legends.

Born in Floral Park, New York, he moved to Los Angeles in 1948, then back to NYC to study at the prestigious Juilliard School, where he majored in classical piano and composition. Subsequently returning west, he struck up a relationship with Henry Mancini, from whom he learned much about the wit, brevity, and subtlety needed to score movies. Often described as a modern neo-romantic with a flair for leitmotif à la Tchaikovsky and Richard Wagner, our hero was in the right place at the right time – though despite his successes as a musician working for Elmer Bernstein, Jerry Goldsmith, and Mancini, he could hardly have expected to compose eight of the Top 20’s most lucrative film scores of all time.

Williams’ learning curve was swift, from Valley of the Dolls to the Robert Altman thriller Images. Knowledge of these, along with Williams’ first collaboration with Steven Spielberg, on Sugarland Express (Spielberg’s directorial feature debut, following the earlier Duel, which was made for TV), is paramount to tracing the development of Williams’ genius.

In 1975, he cemented his friendship with Spielberg on Jaws, which many consider to contain the most recognizable theme tune of all. A clever reinterpretation of the staccato music that accompanies the shower scene in Psycho, it remains the ultimate in classic suspense and, on release, had audiences transfixed – or, in many cases, hiding behind their cinema seats. In terms of official recognition, however, Williams’ original motion picture soundtrack to Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) has been even more feted, with the American Film Institute citing its stirring score as the most memorable of any US film.

You don’t need to be a musicologist to understand why his scores resonate. Williams’ themes are not just an accompaniment to the action – they often are the action, preceding the main event and taking the listener into unknown worlds – underwater or deep space – while raising the neck-hairs. Shortly after Star Wars, he continued at an incredible pace – amazingly, that same year, Williams composed, conducted, and produced the music to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which contained yet another iconic pop culture reference point with the “five-tone” motif whose arrival, during the key moment of contact with the alien life force, still brings a tear to the eye.

Universally lauded by the end of the decade, the very sight of Williams’ name on a film poster guaranteed that a world of wonder lay in wait. Jaws 2 and Superman kept him on a roll that’s unlikely to be equaled (the former is, in parts, even more terrifying than the original movie). And yet the brilliance kept coming with mind-boggling regularity: 1941, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark are key indicators of a composer who knows how to push the right buttons in themes full of exploratory promise, patriotism, derring-do and a sheer musicality that has movie-goers humming Williams’ earworms all the way home.

Fiddler on the Roof, Jaws, and Star Wars deservedly scooped Academy Awards while also forcing Williams’ peers to up their game. But while many composers would rest on their laurels, Williams motored on, thrilling new generations of movie-goers with scores for Return of the Jedi and the Indiana Jones films, all ensuring that he would make as indelible a mark on the 80s as he had on the 70s.

Movie fans are lucky to have lived through a period when Spielberg and Williams are in tandem. Schindler’s List (1993), possibly the director’s most personal and affecting movie, once again brought the classical genius out of Williams. His pieces, many played by the great violinist Itzhak Perlman, nailed his ability to explore multiple atmospheres – it’s the sort of versatility that drew Spielberg to him in the first place. “John is much more of a chameleon as a composer,” the director has noted. “He reinvents himself with every picture.” In reply, Williams acknowledges, “My relationship with Steven is the result of a lot of very compatible dissimilarities.”

A profile in the Los Angeles Times, published in 2012, gives further insight into his modus operandi: “The quietest room in Hollywood may be the office where John Williams composes,” the paper observed. “In a bungalow on the Universal Studios lot, steps from the production company of his most frequent collaborator, director Steven Spielberg, Williams works alone at a 90-year-old Steinway grand piano, with fistfuls of pencils and stacks of composition paper nearby, and worn books of poetry by Robert Frost and William Wordsworth piled on the coffee table.” Refusing to fall back on synthesizers or computers, Williams scores the old-fashioned way; he doesn’t let machines dictate his search for melody.

The end results – the most recognizable themes in modern movie history – are reinforced by the fact that the pair have worked closely together on 25 of 26 feature films directed by Spielberg. And there are no signs of him slowing, either. Yet another generation thrilled to his intelligent scores for the classic neo-noir sci-fi cult classics Minority Report and War of the Worlds, the Harry Potter films, and War Horse, along with lauded returns to the classic franchises via Indiana Jones And The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

In his other life, away from the blockbuster, Williams is just as revered for his classical and standard interpretations, his nods to George Gershwin, the delight he took in working with opera singer Jessye Norman, Chinese-American cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and violinist Gil Shaham. He proudly holds the position of Laureate Conductor for the celebrated Boston Pop Orchestra, adding to his “genius” epithet the words “polymath” and “Renaissance man.”

After six decades of creating music that defines the films they appear in, John Williams remains a shy and private man, blessed with great fame, yet untouched by it. On June 9, 2016, Spielberg was on hand to present Williams with the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award: the first such honor given to a composer in the 44-year history of the award. AFI president and CEO Bob Gazalle summed it up perfectly when he said, “This man’s gifts echo, quite literally, through all of us, around the world and across generations. There’s not one person who hasn’t heard this man’s work, who hasn’t felt alive because of it. That’s the ultimate impact of an artist.”

May the force long remain with this singular genius…

Walt Disney Records has released remastered editions of the original motion picture soundtracks for the first six Star Wars films: A New Hope (1977), The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Return of the Jedi (1983), The Phantom Menace (1999), Attack of the Clones (2002) and 2005’s Revenge of the Sith are available now.