Riot Girls: The Female Musicians Who Changed The World

It wasn’t easy for musicians to be openly feminist – or, indeed, to be openly women. But right from the start, they’ve been there…

Ah, “just another blog about women in rock,” to paraphrase former Bikini Kill frontwoman Kathleen Hanna. But while surely we’re happily approaching the days where we don’t have to say “all-female band” instead of just, y’know, band, it’s still good to pay our respects to those female musicians who cleared, with sweat and struggle, the paths that we now walk.

But it wasn’t always so easy for musicians to be openly feminist – or, indeed, to be openly women. But right from the start, they’ve been there, eking out space, changing the game, one step at a time. And though there isn’t space to thank them all, let’s make a start…

As noted in rock academic Lucy O’Brien’s essential book She Bop, among the very first performers to popularize blues and make a success of selling records were women. The first of the “race records” – tracks aimed at an untapped market of black Americans – released by Okeh Records in 1920 was sung by a woman: Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues.”

The first big success and big personality was Ma Rainey, The Mother Of The Blues, who championed a direct, down-to-earth style, despite making an early stab for rock glamour and excess by wearing a chain of $20 gold pieces and advising her listeners to “Trust No Man.” She began touring as a double-act with her husband, but went on to make over 100 solo recordings, invested the money she made in two theatres, and got to retire comfortably. She also discovered Bessie Smith, who brought blues further into the mainstream during the 20s, a decade when female performers were more successful than men.

Smith could earn up to $200 per side on her recordings, a phenomenal amount when a typical successful male artist might earn around $15. The title of her first recording set the defiant tone: “T’Ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do.” She was known for the way she’d competitively “carve” other artists’ songs, releasing her own, superior version, shortly after theirs, and she dressed with front to match, in glitzy gowns and ostrich plumes. “Smith had several husbands, but they could never control her or her bisexual affairs,” reveals O’Brien in She Bop, which conjures a world of early independent woman, where track titles such as “Ain’t Much Good In The Best of Men Nowaday” or “One Hour Mama” abounded, despite the stereotypical image of the mournful blueswomen devastated by lost love. Women weren’t limited to singing, either: Memphis Minnie’s guitar style adapted from the classic to the electric blues era, and, in 1933, she once beat Big Bill Broonzy in a guitar contest, to the delight of the watching crowd.

As blues mutated into jazz, it was a woman who became its most original, and most lauded voice: Billie Holiday. Though Lady Day suffered greatly at the hands of men – she was raped at the age of 10, and working as a prostitute at the age of 13, having started her working life cleaning in a brothel, where she listened obsessively to their Bessie Smith 78s – she turned her anger and pain into some of the most arresting songs in the popular music canon. “Strange Fruit” was the first time a female singer had been so politically outspoken, so angry, so open about the racism that had blighted her life.

Ella Fitzgerald also broke boundaries, dominating bebop with her versatile voice, which she used like a virtuoso instrument. She was the first black artist to headline The Copacabana, and kept pushing forward in her later years, performing on Quincy Jones’ 1989 album, Back On The Block. Another groundbreaking female artist, Björk, was a fan from her childhood. “Here singing was an influence on me, but not in a direct sense,” she told Q magazine in 1994. “More in the sense that you shouldn’t take melodies too literally… the point is more the mood, and the emotions, and it doesn’t matter if you forget the lyrics. You can still sing the song. You can do whatever you want to.”

Taking that last sentiment to heart, the first woman to have a No.1 record in the US was Connie Francis, an Italian-American New Jersey girl born Concetta Franconero. Having had flop single after flop single, Francis’ contract was almost expired, and she was considering a career in medicine instead. At her final session in 1957, she recorded a cover of a 1923 song called “Who’s Sorry Now?.” It reached No.1 on the UK chart (which US singer and actor Jo Stafford had already topped in 1952 with “You Belong To Me”) and No.4 in the US. In 1960, her track “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” became the first song recorded by a solo female to top the US chart.

Though it took a decorous lady like Connie to crack into hearts and charts, as pop and rock started to diversify into different genres, other women were pushing at the boundaries of what was sonically and visually acceptable. Wanda Jackson, The Queen Of Rockabilly, was no mere accessory to King Elvis, fronting her own radio show from the age of 11, and later touring with her own band. She brought, she said, a glitzy glamour into country with her stage outfits, sewn by her mother, and struck fear into the hearts of no-good cheaters on the likes of 1969’s “My Big Iron Skillet”: “There’s gonna be some changes made when you get in tonight ’Cause I’m gonna teach you wrong from right.”

Bringing blues back into the era of 60s rock, meanwhile, Janis Joplin pushed even harder at the definition of what a female performer could do. Inspired by the likes of Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, she began singing folk and blues at school, where she was bullied not just because of her weight and her acne scars, but also for her love of black music. Joplin was among the first rock frontwomen to take the freedom that the 60s promised – with all its good and bad ramifications – and try to live as free as a man could. Breaking through with Big Brother & The Holding Company at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, her star soon outshone the rest of her group, and she took control in the studio before going solo, providing inspiration to a generation of free female spirits. “After they see me,” she said, “when their mothers are feeding them all that cashmere sweater and girdle, maybe they’ll have a second thought – that they can be themselves and win.”

Also pushing rock boundaries was Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick, who left both her first band and her husband behind to become one of the hippie era’s great frontwomen. With her unusually deep voice, Slick aimed to emulate that most traditionally male of rock instruments, the electric guitar, and she wrote one of acid rock’s defining statements in 1967’s “White Rabbit.”

Over on the pop side of things, Carole King was one of the 60s’ defining musical figures. Born with perfect pitch, she started learning the piano at four. With her songwriting partner and husband Gerry Goffin, she wrote some of the biggest pop and girl-group hits of the era – the likes of “The Loco-Motion,” “It Might As Well Rain Until September” and “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” – becoming the most successful female songwriter of the late 20th Century. Between 1955 and 1999, King wrote or co-wrote 118 Billboard hits, and 61 UK chart hits.

Her hits for others, from “Up On the Roof” for The Drifters, to the peerless “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” for Aretha Franklin, were not the end of the story. In the 70s, King’s own performing career took off, and her classic album Tapestry holds the record for the most consecutive weeks spent at US No.1, at 15 weeks. The album included the barnstorming “(You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman,” which King and Goffin had written for Aretha Franklin, the singer to end them all. Franklin took the gospel power of her church upbringing – Mahalia Jackson was a family friend – to the world of pop, commanding R-E-S-P-E-C-T with a voice of refined power. When Carole King was honored by the Kennedy Center in 2015, Franklin’s performance of “Natural Woman” – complete with fur-coat drop – stole the show.

Making a very different journey through bubblegum pop to solo success was Cher, who, after singing backing vocals on Phil Spector hits such as “Be My Baby” and “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’”, hit the heights with husband Sonny Bono and their dewy-eyed flower-child love anthem “I Got You Babe.” Hippie pop’s power couple were not all they appeared, however, and for years the controlling Bono held Cher’s career back. Her first solo US No.1, 1971’s “Gypsys, Tramps And Thieves,” was, tellingly, produced without his input.

In 1974, Bono filed for a separation on grounds of “irreconcilable differences.” Cher countered with a divorce suit on grounds of “involuntary servitude,” claiming that Bono had withheld from her the money she’d earned. Cher went on to range widely through rock, pop, disco and dance, with highlights including the cannon-straddling video for 1989 power ballad “If I Could Turn Back Time” (banned by MTV, and other channels, thanks to Cher’s outré get-up), and the 1998 vocoder-trance hit “Believe,” which became the biggest-selling hit by a female artist in the UK. In more recent years, she also became an unexpected success on social media, hilariously baiting the Donald Trumps of this world in capital letters.

Talking of leather-clad rock chicks, we should play homage to an original, Suzi Quatro, who challenged gender boundaries by becoming the first famous female rock bassist. Determinedly presenting herself as one of the (tom)boys, Quatro subtly drew attention to double standards. Irked by US record companies trying to make her into the next Janis, she moved to the UK in 1971 to find success on the suggestion of producer Mickie Most, who “offered to take me to England and make me the first Suzi Quatro.” Quatro was no mere puppet, though, and the ferocious way that she laid claim to headbangingly “male” glam and hard rock sounds of the era, as heard in her hits “Can The Can,” “48 Crash” and “Devil Gate Drive,” all million-sellers – marked her out as a true original. Later she’d come to wider recognition in her home country as the rocker Leather Tuscadero on the sitcom Happy Days.

Quatro, alongside her fellow leather enthusiast and Runaways guitarist Joan Jett and beatnik-inspired proto-punk poetess Patti Smith, cleared the way for the women of punk rock such as Akron, Ohio’s Chrissie Hynde, who also moved to the UK to make it, the peerless Poly Styrene and bands such as the Slits and the Raincoats, who seized on punk’s DIY promise to carve their own space. Outlasting the scene’s brief energy flash, and many of the its male figureheads, was Siouxsie Sioux, first ringleader of Sex Pistols’ fan crew the Bromley Contingent, then becoming her own icon at head of The Banshees, whose dark glamour lit new paths through post-punk and goth.

But rough and tough wasn’t the only way to go in the 70s; there was also the path of the diva. Though Diana Ross’ success with The Supremes isn’t usually held up as a paragon of sisterly solidarity, her huge star power as a black woman bestriding Motown, pop and disco was undeniably a breakthrough and an inspiration to many subsequent women: with 70 hit singles and 18 No.1s, she remains the only artist to have reached the top as a solo artist, a duet partner, as part of a trio, and in an ensemble; Billboard magazine named her the “female entertainer of the century” in 1976.

Barbra Streisand also sets a high bar: originally planning a career as an actor, she thought she’d try singing as an added bonus. After she took part in a talent contest at a local gay nightclub, the club’s owners were so astounded that they booked her to sing there for several weeks, and her performing career began. Early on, she began mixing songs with comedy and theatricality in her shows. Distinguished theatre critic Leonard Harris was impressed, writing, “She’s 20; by the time she’s 30 she will have rewritten the record books.” He wasn’t wrong: Streisand has sold millions of records and raked in millions more at the box office, and she’s the only artist to have No.1 albums in six decades.

The first UK No.1 album by a female artist, meanwhile, was Kate Bush’s Never For Ever. A landmark in more than one way, it was released at a juncture in Bush’s career where she seized control, setting up her own publishing and management company, and taking more and more control over the production of her records. From her next album, The Dreaming, onwards, Bush was in full control, pushing pop to its most experimental edges, and pioneering the use of electronic instrumentation, such as the Fairlight sampler.

Bush opened paths for women in alternative music, but we should honor, too, those who broadened out the mainstream, such as Madonna, the mother of record-breaking. Moving from Michigan to New York with only $35 and a blond ambition that overcame her fear – “it was the first time I’d ever taken a plane, the first time I’d ever gotten a taxi cab” – she is, still, the bestselling female recording artist of all time, and frequently held up as one of the most influential. Her frankness and in-your-face sexuality, and her wild, unashamed success, inspired generations of women. From her lace-and-“BOY TOY” T-shirt days to the graphic provocations of her Sex book, Ciccone loved to challenge, and to nip at the heels of the Catholic religion in which she was raised: the first and best of pop’s good-girls-gone-bad.

Blazing her own trail from ingenue to goddess at around the same time was Whitney Houston, a singer seemingly born to greatness: Dionne Warwick was her cousin, Darlene Love her godmother, and Aretha Franklin her honorary aunt. Houston’s eponymous first album was the best-selling debut by a woman in history, and she is the only artist ever to have seven consecutive Billboard No.1 singles. Despite the troubles of her later life, she was an inspiration not just in the field of music, but in film, with 1995’s Waiting To Exhale in particular still held up as a watershed of mainstream representation of black women in cinema.

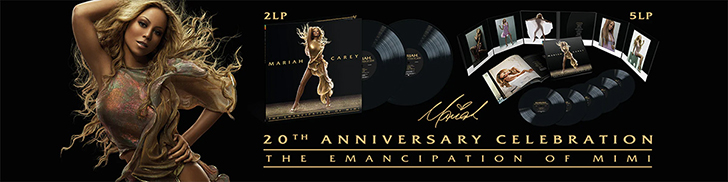

Mariah Carey, too, started out as a good girl, in a classic protégé mould: discovered and shepherded by manager-husband Tommy Mottola, her rafter-shaking power ballads sold phenomenal amounts. But Mariah wanted more. She divorced Mottola and seized control with 1995’s Daydream album, adopting a more contemporary R&B sound, enlisting guest rappers such as Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Jay Z, and sampling Tom Tom Club. “Everybody was like, ‘What, are you crazy?’” she said at the time. “They’re nervous about breaking the formula. It works to have me sing a ballad on stage in a long dress with my hair up.” The result, though, was higher sales than ever; her peerless single “Fantasy” saw her become the first female artist to debut a single at No.1 on the Billboard Top 100. And in shifting her squeaky-clean balladeer image to a more playful divadom, Carey became one of our most beloved pop stars, and proved that she knew best.

Janet Jackson, too, started out in the shadow of men – not just her hugely famous brothers, but her domineering father – appearing in family productions from the age of seven. Her artistic and commercial breakthrough, Control (1986), saw her moving away from her father’s influence towards creating, with producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, a tough, smart persona. Enduring classic “Nasty” was inspired by men who catcalled her in the street on the way to the studio. “I’ve got a name, and if you don’t know it, don’t shout to me in the street,” she said. “‘Control’ meant not only taking care of myself, but living in a much less protected world. And doing that meant growing a tough skin.” By the release of her next album, Rhythm Nation 1814, she’d sacked her father as manager.

Moving into the 90s, one ingénue who was certainly paying attention to the bath of her forebears was Madonna’s future kiss-partner Britney Spears, who broke through in the video for her platinum single “… Baby One More Time,” playing the tongue-in-cheek part of a Catholic schoolgirl with unclean thoughts. Spears’ struggle to gain control over her adult image became a template to follow or react against for female pop stars making the transition from child star to adult artist, from Miley Cyrus to Selena Gomez. In 2008, Britney became the first female artist to have all her first five albums debut at No.1 in the US, and the youngest female artist to have five No.1 albums.

Alt.rock’s commercial breakthrough in the 90s was spearheaded by women from Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon to Liz Phair (who once described Madonna as the speedboat who pulled other female musicians behind her on jet skis). Courtney Love was grunge’s supremely self-aware Janis, her raw-rage voice and fearless frankness inspiring a generation, while Bikini Kill, Babes In Toyland, Sleater-Kinney and the riot grrrls brought feminist politics into music more explicitly and unapologetically than ever before, and the likes of Tori Amos and Alanis Morrissette brought some of that anger and energy into the mainstream. . (Tori remains committed to exorcising her rage on record. Her latest album, Native Invader, pulls no punches in criticising the Trump administration.)

In the proud and open feminism of today’s pop megastars, we can see the legacy of those 90s women all around us, but it might be some time before we can truly measure the influence of Beyoncé. Like many on this list, her story is one of increasing control. Her early success with Destiny’s Child, with game-changing, smart, sharp, R&B-pop hits including “Jumpin’, Jumpin’,” “Bills, Bill, Bills,” “Survivor” and “Independent Women (Part 1),” came under the aegis of her father-manager Matthew Knowles, with Beyoncé suffering depression after he sacked band members and she copped the public blame. Matthew continued as her manager through her solo success from “Dangerously In Love” (recorded with future husband Jay Z) onwards. In 2010, Beyoncé took a career break on her mother’s advice, and, in 2011, parted ways with her father as manager.

From then on, things got seriously interesting: her album 4 was heralded by the tough, baile-funk influenced “Run The World (Girls),” a motto Beyoncé lived by more and more closely. The surprise release of her self-titled album and accompanying film in 2013 marked a step-change in her output, with frank and graphic lyrics, and darker, stranger production, opening up more of her thoughts than ever before. The all-conquering Lemonade sealed the deal, taking on not just unfaithful husbands, but, in the infectious “Formation,” systemic racism. Her proud support of feminism and the Black Lives Matter movement, along with her fellow megastar, and darker, stranger production, has changed the game. Rihanna, who took part alongside Beyoncé and many others in powerful Black Lives Matter video, has also pushed the boundaries of what mainstream stars are supposed to talk about with songs such as “American Oxygen” and her dark, frank Anti album – a long way from the sweet-smiled Barbadian 17-year-old who released Music Of The Sun in 2005.

And in a more crass measure of female power, Beyoncé and Rihanna are also consistently among the top musical earners over the past few years. So too is Katy Perry, who, like Carole King, is a songwriter who found her own success, and whose candy-pop image sends up a princessy, bubblegum idea of femininity as she fires out empowerment anthem after empowerment anthem.

Perry’s fellow lover of pop grotesque, Lady Gaga, meanwhile, is the ultimate self-created icon, springing fully formed from her own weird brain. From the start, she presented herself as a ready-made star: a breakthrough single called “Paparazzi,” and an album called The Fame. And writing her own legend worked – she’s now one of the highest-selling artists ever, with an estimated 114 million album sales, and the proud owner of six Grammys and three Brit Awards. She’s used that success to stand up for others, sharing her own story of being raped at the age of 19, and performing her song on the subject, “Til It Happens To You,” surrounded by sexual assault survivors at the Oscars.

It used to be the case that there was only room for one woman at the top table, but, hearteningly, female solidarity has become an increasingly important story in pop. Taylor Swift, who writes some of the most irresistible pop songs in the game, and breaks records every time she breathes, underwent an enthusiastic public conversion to feminism, championing her friends in a way that counteracted the media’s tendency to set female stars against each other.

One of those friends, Lorde, was hailed by David Bowie himself as the future of music. When she parted ways with her manager Scott MacLachlan before the release of her second album, Melodrama, there were online mutterings to the effect that it might not be the wisest of ideas. “Hey men,” she tweeted in response, “do me and yourselves a favor and don’t underestimate my skill.” That future seems to be in safe hands.