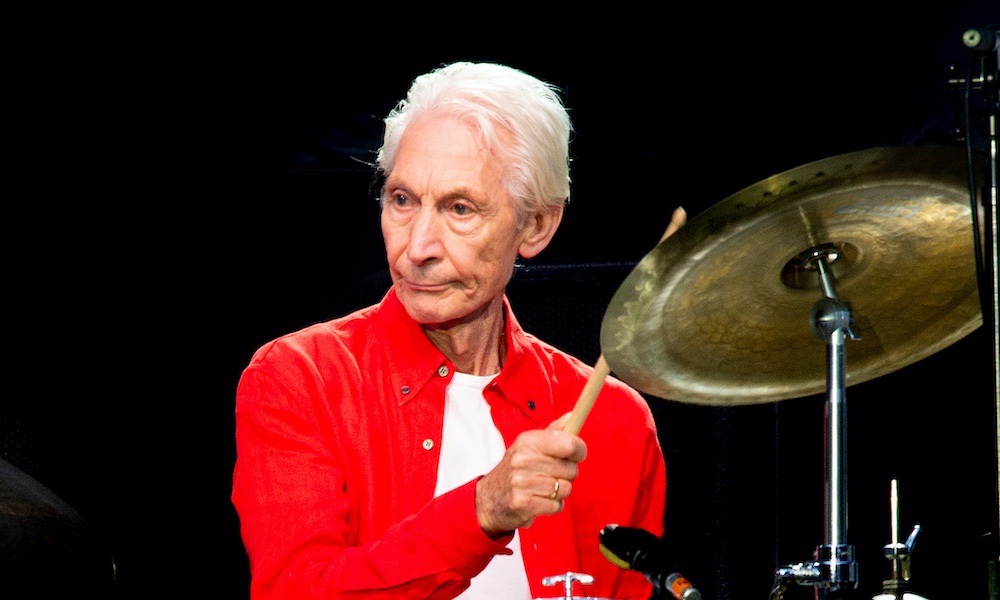

Charlie Watts, Beloved Rolling Stones Drummer Of Nearly 60 Years, Dies Aged 80

Watts joined the Stones in January 1963 and was a constant presence in the group from that day forth.

Charlie Watts, beloved drummer with the Rolling Stones and one of the most admired musicians of the rock era, has died at the age of 80. The news was confirmed by Watts’ publicist.

“It is with immense sadness that we announce the death of our beloved Charlie Watts,” a statement said. “He passed away peacefully in a London hospital earlier today surrounded by his family. Charlie was a cherished husband, father, and grandfather and one of the greatest drummers of his generation. We kindly request that the privacy of his family, band members, and close friends is respected at this difficult time.”

Watts played his first gig with the Stones in January 1963, some seven months after their live debut, and after being energetically sought-after by his future bandmates. From that day forward, he was a constant on the drum stool for the better part of 60 years, until he was forced to miss the resumption of the band’s No Filter tour in the US in September 2021 while recuperating from a medical procedure.

Charlie’s preeminence as a drummer was beyond dispute, and frequently eulogized by his fellow Stones, particularly Keith Richards, who took time in countless interviews to say how lucky he was to play with Watts behind him, and how he could not imagine the Stones without him.

“Charlie’s always there, but he doesn’t want to let everybody know,” he said in 1979. “There’s very few drummers like that. Everybody thinks Mick and Keith are the Rolling Stones. If Charlie wasn’t doing what he’s doing on drums, that wouldn’t be true at all. You’d find out that Charlie Watts is the Stones.”

But the other ingredient that made him so warmly loved by friends and strangers alike was his extraordinary humility. He truly hated to be in the spotlight, and was famously reluctant to take a bow, or to speak, when introduced on the band’s stadium and arena shows – which only made the applause from scores of thousands of fans even louder. All of this with what was widely held to be the smallest drum kit in all of rock’n’roll, totaling perhaps seven items. On their second live album Get Your Ya- Ya’s Out!, Mick Jagger says: “Charlie’s good tonight, isn’t he?”

He was far more comfortable in the world of his first love, jazz, happily fronting his own groups and playing in others, on stage in small clubs and often on record, in a variety of line-ups from big bands to quintets and quartets. But even here, Watts made every effort to deflect the limelight in favor of his fellow musicians. His private life, too, was as un-rock’n’roll as could be: away from touring, he moved to a horse stud farm in rural Devon, stabling Arabian horses with his wife Shirley, to whom he was married in 1964.

Charles Robert Watts was born in Wembley, north London, on June 2, 1941 (Mick Jagger would sometimes refer to him in his stage introduction as “the Wembley whammer”). Like Brian Jones and Bill Wyman, he was named after his father who, after being demobbed from World War II, worked as a driver with British Railways. His mother Lillian was a homemaker, and Charlie and younger sister Lydia (born in 1944) grew up in no great comfort, in a “prefab” house, as constructed in the hundreds of thousands in Britain after the widespread bomb damage from the war.

Watts would later say that the record that made him decide he wanted to be a drummer was the 1952 disc “Walking Shoes,” by West Coast saxophonist Gerry Mulligan with Chico Hamilton on drums. Charlie received a drumkit from his parents when he was 14 and was playing around town by 16.

In 1961, as a largely unknown 20-year-old, Watts demonstrated his passion for jazz by writing the cartoon-filled tribute book to Charlie Parker, Ode To A High Flying Bird, published after the Stones became famous. He would often cite the importance of British musician Alexis Korner, who in many ways represented the meeting point between the burgeoning jazz and rhythm and blues scenes in London.

At Korner’s invitation, Watts joined his band Blues Incorporated, but only after a work stint in Denmark, following which he played briefly with future comic and film star Dudley Moore’s jazz trio. In Korner’s group, he met a young singer then known as Mike Jagger, who was singing on the scene in between studies at the London School of Economics.

But, for all the admiring comments and his pursuit by the fledgling Stones, Charlie stayed put in his job as a graphic designer in an advertising agency. Even after his first gigs with the Stones, he didn’t turn fully professional until June 1963, after the band had signed to Decca and released their first single, on which he played, a version of Chuck Berry’s “Come On.”

By 1964, the Stones’ upward trajectory was irreversible, but for all their new-found fame and financial prosperity, their drummer showed no appetite for its temptations. At the first opportunity, he moved out of the shabby flat that band members shared in Edith Grove, Chelsea, to buy his own large property in Sussex.

For decades to come, as controversies, deaths, drug busts, and personnel changes swirled around the Stones, Watts was their percussive and emotional rock. Ironically, his most wayward indulgencies with drink and drugs came in the 1980s, when most of his bandmates were beginning to live more soberly. On disc and on stage, whatever mood was required, he met it and enhanced it, from frenetic hits like “19th Nervous Breakdown” to rock staples like “Honky Tonk Women” and “Start Me Up,” via the brooding menace of “Gimme Shelter” and on to the subtleties of “Waiting On A Friend.”

He never chose to listen back to the band’s recordings for his own interest, but would say that he could appreciate them if they happened to come on at a party. Watts affected diffidence about his membership of the “greatest rock’n’roll band in the world,” but also carried great pride with him about their collective achievements. In 2010, he said: “I kept trying to explain to a guy interviewing me that being in the Rolling Stones is one thing, but looking at it from the outside…I’ve never done it, never had the interest or inclination. But being in it is wonderful.”

He was openly unenthusiastic about the demands of worldwide travel, albeit in great comfort, for the band’s increasingly epic tours, and similarly critical as their set lists spiraled towards two and a half hours of stagetime. To contain his boredom, he made a sketch of every bed he slept in during a tour, a habit that he compared to keeping a diary.

The rest of his spare time on tour was spent either watching other visiting musicians at jazz clubs, or shopping for suits and shoes, another passion. “I have a very traditional mode of dress,” he told GQ. “Old English. I go to all the shops, wherever I am, but nothing fits me because I’m too small.”

When it came to jazz, he would enthuse all day, remembering early records in his collection by Parker and Jelly Roll Morton, which he played with childhood friend and later collaborator Dave Green. He greatly admired such drummers as Elvin Jones, Art Blakey, Phil Seamen, Roy Haynes, Tony Williams, and so many more, and deflected all comparisons with their brilliance.

In 2001, Watts took his turn as the “castaway” on the long-running BBC radio series Desert Island Discs, selecting Parker’s “Out of Nowhere,” Frank Sinatra’s “Night and Day,” and “Jack the Bear” by Duke Ellington & his Orchestra among others. His love of cricket was reflected in the choice of a recording of a commentary from a 1956 Test Match; his book choice was Collected Poems 1934-52 by Dylan Thomas. His favorite among his selections would have surprised many, Igor Stravinsky’s Dance of the Coachmen and Grooms, from Petrushka. His luxury item, drumsticks, less so.

But when the Stones’ schedule allowed, he worked extensively in jazz line-ups, with the Charlie Watts Orchestra in the mid-1980s and a Quintet through the 1990s, including on two albums of Great American Songbook interpretations, Warm and Tender (1993) and Long Ago and Far Away (1996).

With great friend Jim Keltner, he released the instrumental Charlie Watts-Jim Keltner Project in 2000, and performed and recorded with the ABC&D of Boogie-Woogie, featuring pianists Axel Zwingenberger and Ben Waters with Dave Green on bass, leading to the album The Magic of Boogie Woogie in 2010. “This band is the nearest thing to a 1939 night at [New York club] Café Society, for me,’ he said. “That’s my ideal of what it should be like.

Keltner told Drum! magazine of his friend’s style: “He can’t explain it and I don’t necessarily like going into too much detail with him about it. I just marvel at it.” Watts, speaking in 2008, summarized his approach thus: “I was brought up on the theory that the drummer is an accompanist. I don’t like drum solos. I admire some people that do them, but generally I prefer drummers playing with the band. The challenge with rock and roll is the regularity of it. My thing is to make it a dance sound; it should swing and bounce.”