‘Pinkerton’: Rivers Cuomo Embraced His Dark Side And Made Weezer’s Masterpiece

With ‘Pinkerton,’ a disillusioned Rivers Cuomo steered Weezer to its most essential album, but the band would never be the same afterwards.

When Weezer released their debut album in 1994, just one month after Kurt Cobain’s suicide, it’s safe to say that no one was betting on the band to be the saviors of alternative rock. In contrast to Nirvana’s anthems for disaffected youth, Weezer wrote singalong songs about geeking out in your garage and sweaters coming undone. Not to mention, they loved hard rock and heavy metal bands like KISS and Metallica, right down to their heroic guitar solos. Against all odds, however, Weezer (aka “The Blue Album”) was a smash, selling almost a million copies in the US by the end of the year. When it came to creating its follow-up, Pinkerton, expectations were high.

Weary of the rock-star life

Like many of his grunge contemporaries, frontman Rivers Cuomo had grown weary of the rock-star life – living in tour buses and motels for months, feeling isolated from his adoring fans. He also wanted to move away from the “simplistic and silly” songs of “Blue Album” and try writing darker, more complex material. On top of that, he was in physical agony after undergoing a series of surgical procedures to extend one of his legs.

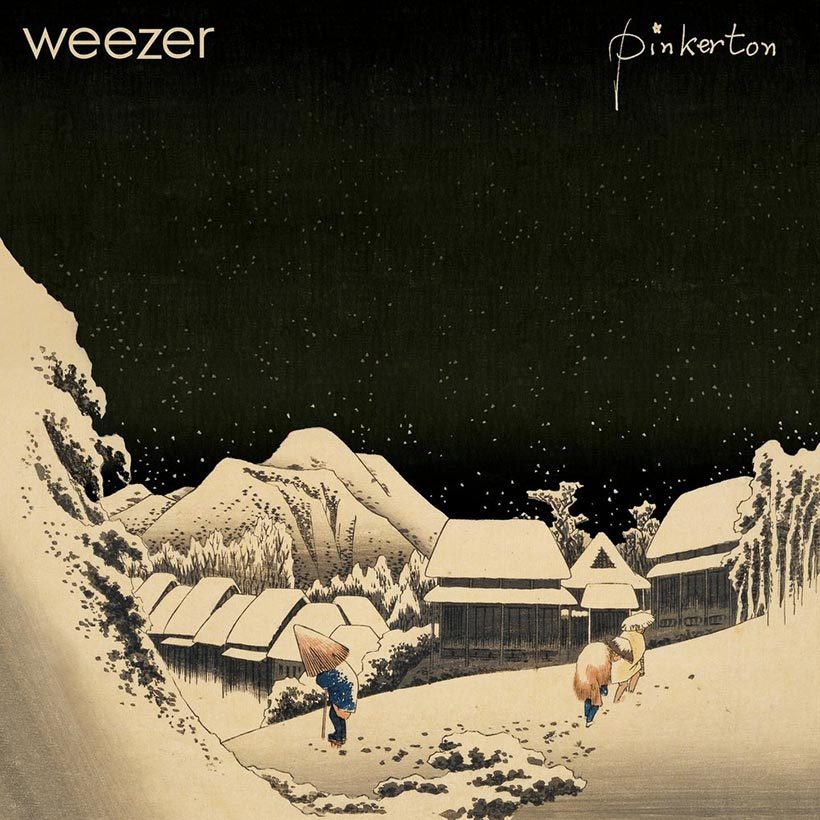

To cope with his emotional and musical frustrations, Cuomo listened obsessively to Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, an opera about the marriage between a Japanese girl, Cio-Cio-San (the Madame Butterfly of the title), and an American naval lieutenant, BF Pinkerton. After a year of channeling his depression and disillusionment into his own songwriting, Cuomo emerged with an album he named after the opera’s male protagonist.

Desperate to find something like love

Simply put, both Madama Butterfly and Pinkerton are about men who’ve done heinous things to the women in their lives. Madama Butterfly ends with Butterfly, finally realizing that Pinkerton never loved her, killing herself as he watches. The marriage at the center of the story is really in name only: Lieutenant Pinkerton weds a child and then abandons her. Weezer’s Pinkerton ends with “Butterfly,” in which Cuomo – or the album’s fictionalized version of him – mourns the death of his pet insect while reflecting on every woman he’s hurt.

“I did what my body told me to/I didn’t mean to do you harm,” he pleads in the chorus. But that’s not an apology, it’s an excuse, especially when you consider the themes explored earlier in the album: emotional abuse (“Getchoo”); seeking sexual relations with a lesbian (“Pink Triangle”); and, in what’s arguably Pinkerton’s most unnerving moment, reading a letter from a teenage fan while fantasizing about her (“Across The Sea”).

Click to load video

Unlike the Pinkerton of the opera, Cuomo at least knows what he’s doing, and he provides us with a window into his own turmoil. Sleeping with groupies every night, as depicted on “Tired Of Sex,” has made him… well, tired of sex, and desperate to find something like love.

“A hugely painful mistake”

He’s too scared of loneliness to end an unhealthy relationship on “No Other One;” she uses drugs, he doesn’t like that she’s friends with his friends. By the very next song, however, “Why Bother?,” he decides that being alone forever is the only way to protect himself from the pain of heartbreak. Elsewhere, “The Good Life” suggests that Cuomo is living anything but. Along with “El Scorcho,” it’s probably one of Pinkerton’s most autobiographical songs, and certainly its most painful.

Even when it’s difficult to determine whether Cuomo is singing in character or as himself, his lyrics are thought-provoking, funny, even relatable – or some combination of the three. And Pinkerton is so loud, raw, catchy and visceral that its many musical pleasures can’t be denied: the guitar feedback in “Tired Of Sex” that becomes its own instrument; the bone-crunching, surf-rock riffs of “Why Bother?” and “Falling For You,” which hit you like a tidal wave; the wave of distortion that washes the delicate melody of “Pink Triangle” out to sea. When you finally come to “Butterfly,” you’re practically exhausted, which makes the closing song’s acoustic tenderness all the more devastating.

Click to load video

Released on September 24, 1996, Pinkerton was greeted with mixed reviews, but the album enjoyed something of a revival two decades later when it became certified platinum. Following the critical response to Pinkerton, however, Cuomo sank into a crushing depression for several years; at his lowest, he lived in a blacked-out apartment under a freeway outside Los Angeles. When he re-emerged in the new millennium, he returned to writing the “simplistic and silly” songs he had scorned before, dismissing Pinkerton as “a hugely painful mistake.”

The cult of Pinkerton

But by then, Pinkerton’s cult had grown. Six years after panning it, Rolling Stone’s readers voted it the 16th greatest album ever, and critics retrospectively hailed the album as a masterpiece. Even Cuomo himself came around, praising the authenticity of his songs, and on Weezer’s Memory Tour in 2010, the band played the full album live to fans who sang every word back at them.

Click to load video

Pinkerton is a timeless album, no doubt, but it’s also an album fixed in a certain time. When Cuomo wrote it, he was a still-maturing young man who desperately wanted love, sometimes confusing it for sex; to this day, that describes a substantial share of Weezer’s audience. As long as there are teenagers on this planet – so, forever – there are going to be listeners who hear Cuomo singing to them, for them, on Pinkerton.

Cuomo isn’t that guy anymore. Since Pinkerton, he has released over ten more albums with Weezer. He’s happily married with two children. He’s at peace. He’ll never make another album like Pinkerton, but we’re glad that he did.