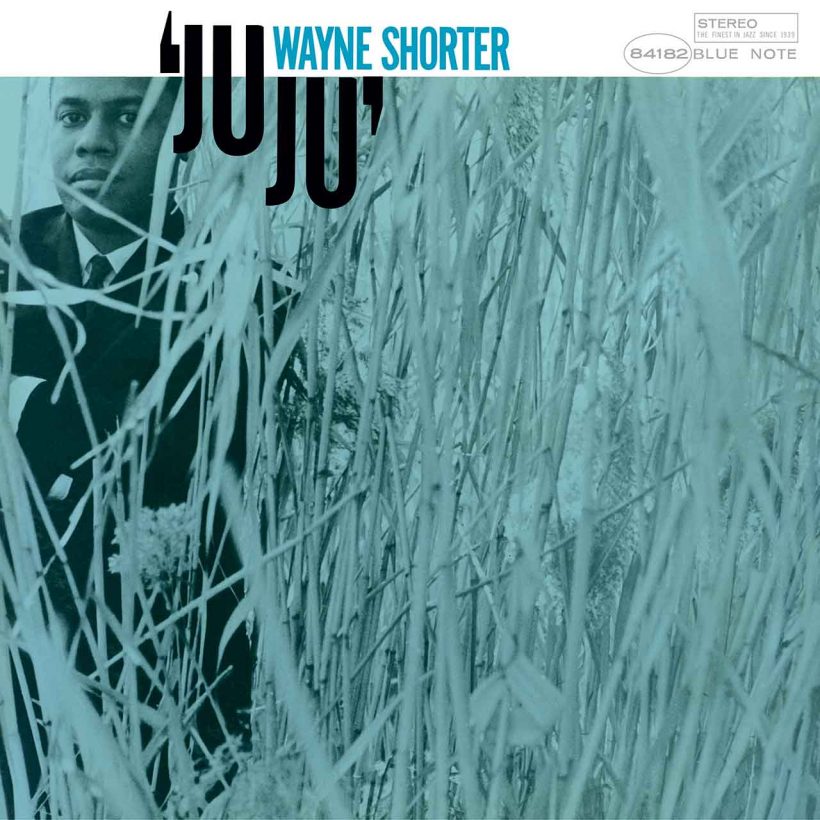

‘JuJu’: Wayne Shorter’s Spellbinding Second Blue Note Album

The tenor saxophonist’s collaboration with John Coltrane’s rhythm section yielded magical results.

After two fairly underwhelming collections of orthodox hard bop for the Chicago indie label Vee-Jay – 1959’s Introducing Wayne Shorter and 1962’s Wayning Moments – tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter landed at New York’s Blue Note Records in 1964 where, with a series of consistently excellent recordings, he rapidly blossomed into one of the modern jazz era’s finest composers. In August 1964, four months after recording Night Dreamer, his darkly brilliant debut for the label, 30-year-old Shorter returned to Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey to record a follow-up LP. Using the same musicians that helped bring Night Dreamer to life – pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Reggie Workman, and drummer Elvin Jones, all members of the trailblazing John Coltrane Quartet – Shorter created JuJu, an early masterpiece in his canon.

Shorter was still with drummer Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers when he joined Blue Note, replacing Benny Golson as the band’s saxophonist-composer in 1959. Blakey encouraged Shorter’s efforts at composition, instilling a sense of directness, precision, and purpose. “We had fun with Art learning what we called at that time ‘getting to the point,’” Shorter told this writer in 2012. “He said, ‘Get to the point playing jazz and don’t spend time practicing when you’re making a record. If you want to practice something, practice not repeating an idea, a thought, or an expression.’”

Listen to Wayne Shorter’s Juju now.

Taking on board Blakey’s dictum, Shorter began writing music that studiously avoided hard bop cliches. In his four years with the drummer, he developed a distinctive, uniquely individual, style as a composer, writing some of the band’s best-loved tunes, including “Lester Left Town,” “Ping Pong,” and “Backstage Sally.” Though allowed to record with Vee-Jay as a leader shortly after joining The Messengers, the young saxophonist didn’t seem ready for the responsibility of making a solo record. Despite his exemplary work in The Messengers, his first two albums, though promising, fell short of expectations. At Blue Note, however, under the guidance of producer Alfred Lion, a seemingly transformed Shorter rose to the challenge, fulfilling the early potential he’d shown.

If Night Dreamer showed us the real Wayne Shorter – innovative, brilliant, and fearlessly pushing musical boundaries – then JuJu drew us deeper into his arcane world with its occult themes and references to far-off cultures. The opening title track “JuJu” – alluding to the West African belief in the power of magic – found Shorter blowing keening horn notes over Tyner’s mysterious chord changes and Jones’ unsettling polyrhythms. Though the track had a Coltrane-like intensity, Shorter’s penchant for concise but pithy musical statements and epigrammatic phrasing made it totally unique.

Despite its title, the free-flowing “Deluge” proved less intense than the opener, while “House Of Jade” was an elegant slow blues showing Shorter at his most lyrical. “Mahjong” – named after the Chinese game – unsurprisingly was imbued with a decidedly Eastern feel. In sharp contrast, the hard-charging “Yes Or No” was a no-frills modal-tinged hard-bop piece. The closing track, “Twelve More Bars To Go” possessed a looser feel, showing Shorter immersing himself in the blues. “The picture I had in my mind was of someone having a very good time, going around to every bar in town,” he revealed in JuJu’s liner notes.

In September 1964, a month after JuJu was completed, Miles Davis – who had been trying to tempt the saxophonist away from The Messengers for several years – finally succeeded in luring Shorter into his band’s new lineup. The saxophonist would go on to do great things in Miles’ band, cementing his status as one of jazz’s greatest composers. But he also continued his parallel solo career at Blue Note, staying with the label until 1971 when he left to co-found the fusion supergroup Weather Report. Miles Davis’ appreciation for Shorter’s talents should have come as no surprise, though. JuJu is spellbinding, an album where you can literally hear Shorter formulating his individualistic approach to playing and composing.