The Velvet Underground See The Light On Self-Titled Third Album

Escaping from the darkness of ‘White Light/White Heat,’ The Velvet Underground’s self-titled third album turned down the volume and turned up the warmth.

Where the hell are you meant to go after White Light/White Heat? Released in early 1968, The Velvet Underground’s second album was a pointedly harsh, brutal, chemical statement, containing several performances which came close to tipping over altogether into black-hearted anarchy. Carrying on like this would, perhaps literally, have killed them. By the time of the VU’s self-titled third album, however, things had very much changed.

Listen to the deluxe edition of The Velvet Underground’s self-titled album now.

In the stunned wake of White Light/White Heat, violist/organist/bassist John Cale left the band. Cale, a dauntless experimentalist, was a key architect of the grainy, saw-toothed textures which characterized the first two Velvets albums… and his replacement couldn’t have been more different.

“They needed to balance it out”

Doug Yule, a soft-voiced guitarist from Boston, had been playing with The Glass Menagerie when his abilities came to the attention of Velvets guitarist Sterling Morrison. Yule had been living in his band manager’s large apartment – sometimes frequented by various combinations of Velvets whenever they were passing through – and when Morrison happened upon Yule diligently practicing one fateful day, he passed a warm recommendation on to Lou Reed.

With Cale out of the picture, Yule was duly drafted into the Velvets to play bass and organ. In an interview for the online music mag Perfect Sound Forever, Yule gnomically observed, “John [had been] a Pisces, Lou was a Pisces, Moe [drummer Maureen Tucker] and Sterling were Virgos… and I was a Pisces. They needed a Pisces to balance it out.”

Reveal the fathomless depths

Recordings for the third Velvets album began in Hollywood’s TTG Studios in November 1968. The conspicuously restrained songs that Reed brought to the table were deliberately at odds with White Light/White Heat’s static-flecked ozone of channeled chaos and cranked amps. The songwriter intuited that another album in the same distended vein would dilute the impact of both… besides which, the Velvets had been written off too often as mere sensationalists – a one-trick freak show. It was time to reveal the fathomless depths beneath the shiny, shiny leather and peel-off bananas.

Of course, the clues had been hiding in plain sight straight from the outset, with their debut album’s bruised, tender interludes “Sunday Morning” and “I’ll Be Your Mirror.” But when the third Velvets LP, matter-of-factly entitled The Velvet Underground, appeared in March 1969, it took this hushed vulnerability to the next level (downwards).

Warm, simple, humanitarian

Plain-speaking, frail and small, the Yule-sung “Candy Says” made for a bravely muted opening track. Taking the transsexual Candy Darling as its nominal subject (glimpsed in the Andy Warhol film Flesh and, later, appearing at length in Warhol’s 1971 satire Women In Revolt), the song demonstrated an ahead-of-the-game sensitivity, applicable in any number of wider contexts – “I’ve come to hate my body/And all that it requires in this world” – and, as such, continues to resonate across a hearteningly broad listener base.

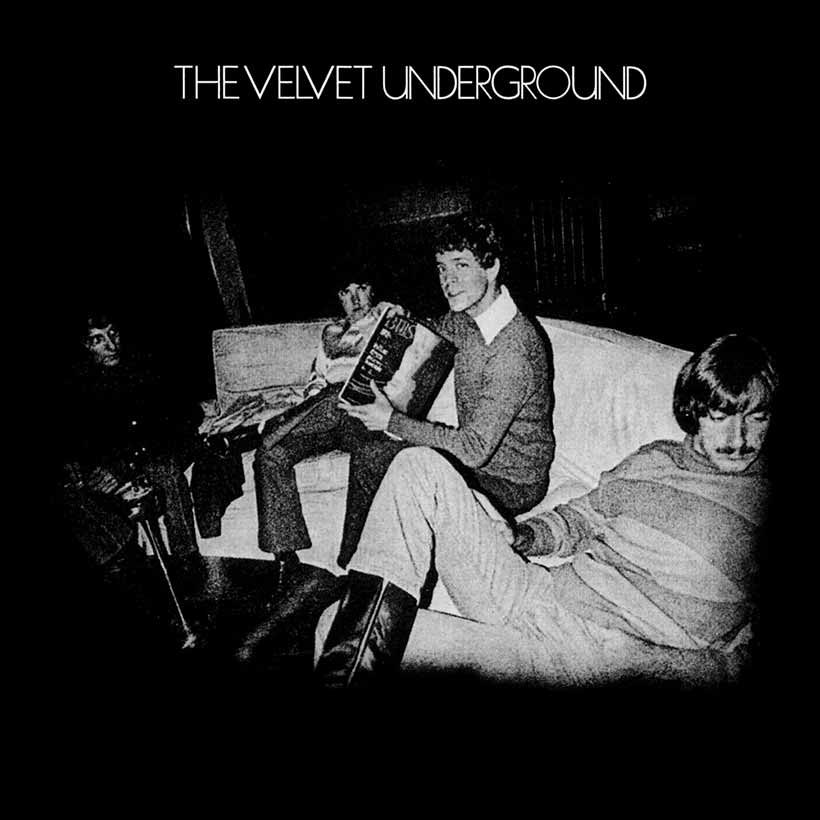

As a by-product, “Candy Says” was also one of a handful of songs on the album which birthed an entire subset of unrepentantly awkward, wilfully naïf indie rock, delivered by bands who apparently took sartorial cues from Reed’s collegiate look on the album’s front cover. “I’m Set Free,” the weightless, sincere “Pale Blue Eyes” (reputedly written with Reed’s former girlfriend Shelly Albin in mind), the appropriately hymnal “Jesus”… it was easy to interpret – or misinterpret – these spare, candid meditations as subconscious pleas for redemption, not least given the adulterous scenario set out in “Pale Blue Eyes”: “It was good what we did yesterday/And I’d do it once again/The fact that you are married/Only proves that you’re my best friend… But it’s truly, truly a sin.”

“Let us do what you fear the most”

But it wasn’t all calmness and confession. The thrumming “Some Kinda Love,” like a low-voltage Creedence Clearwater Revival, swerves from non-judgemental (“No kinds of love are better than others”) to waspish (“And of course you’re a bore/But in that you’re not charmless”) and eventually strays into unsettling territory (“Let us do what you fear most/That from which you recoil”).

The obliquely experimental “The Murder Mystery,” meanwhile, outdoes White Light/White Heat’s “The Gift” by presenting two simultaneous narratives, panned either side of the stereo spectrum: Morrison and Tucker in the left channel, Reed and Yule in the right. The real shock is the fact that the organ trills wouldn’t sound out of place on a Doors or Strawberry Alarm Clock album. It’s not regressive, as such, but represents one of the few moments on a VU record that sounds nailed into its timeframe.

And what were “Beginning To See The Light” and “What Goes On” if not hearty, good-time rockers? The former in particular is a gush of irrepressible euphoria (“There are problems in these times/But whoo, none of them are mine”), with Moe Tucker’s drumming poised impeccably in the sweet spot between implacable forward momentum and the lazy back of the beat. Tucker’s is the closing voice on the album, imbuing Reed’s “Afterhours” with a disarmingly sweet approachability.

And the beauty of the VU’s daunting reputation is that a suite of generally warm, simple, humanitarian songs was still construed as subversive in certain quarters. We’d count that as a win on every front.

The Velvet Underground’s self-titled third album can be bought here.