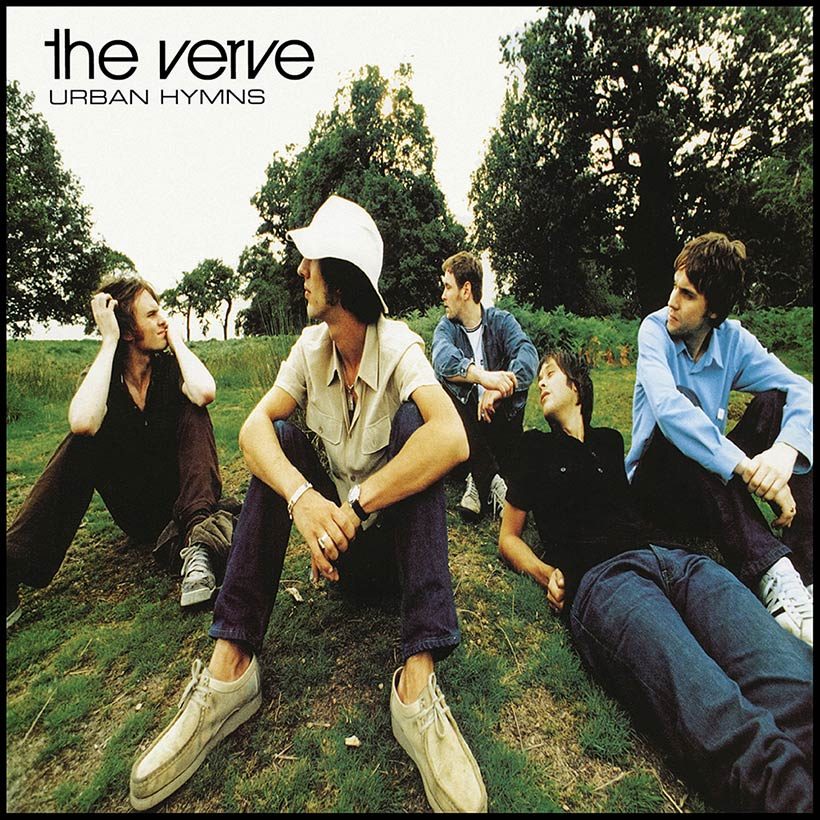

‘Urban Hymns’: How The Verve Became Indie Rock Gods

Knocking Oasis off the top of the UK charts, The Verve circa ‘Urban Hymns’ were a force of nature capturing the zeitgeist as Britpop went into decline.

When Oasis’ feverishly-anticipated third album, Be Here Now, was released in August 1997, it rocketed to the top of the UK charts, becoming the fastest-selling album in British chart history. Yet the celebrations were brief and strangely muted, for it was the record that knocked Be Here Now off the top of the UK Top 40 – The Verve’s Urban Hymns, that captured the zeitgeist as Britpop went into terminal decline.

Fronted by the intensely charismatic Richard Ashcroft and precociously talented sonic foil, lead guitarist Nick McCabe, the idealistic Lancashire quartet had promised something of this magnitude from the moment they signed to Virgin Records offshoot Hut in 1991. Produced by John Leckie (Radiohead, The Stone Roses), The Verve’s 1993 debut, A Storm In Heaven, was an ethereal, psychedelia-streaked beauty of considerable promise, while its acclaimed successor, 1995’s A Northern Soul, veered closer to the mainstream, eventually peaking inside the UK Top 20.

Though contrasting with the hedonism inherent in Britpop, the introspective A Northern Soul had still generated two British Top 30 hits, “On Your Own” and the keening, string-kissed ballad “History.” both of which suggested that Richard Ashcroft was rapidly emerging as a songwriter of major significance.

Going gold, A Northern Soul left The Verve seemingly all set for crossover success, yet with the band burnt out by the usual rock’n’roll symptoms of excess and exhaustion, Ashcroft rashly split the group just before “History” began climbing the charts. As events proved, however, the band’s split was only temporary. Within weeks, The Verve were back in business, albeit minus guitarist Nick McCabe, but with the addition of new guitarist/keyboardist Simon Tong, an old school friend who’d originally taught Ashcroft and bassist Simon Jones to play guitar.

The band already had working versions of emotive new songs, including “Sonnet” and “The Drugs Don’t Work,” with Ashcroft having written the latter on Jones’ beaten-up black acoustic guitar early in 1995. Instead of the exploratory jams that produced The Verve’s earlier material, these vividly and finely-honed songs were the logical extension of A Northern Soul’s plaintive ballads “History” and “On Your Own,” and they reflected the direction The Verve tenaciously pursued as they started work on what would become Urban Hymns.

“Those two tunes [‘Sonnet’ and ‘The Drugs Don’t Work’] were written in a much more definitive way… more of a singer-songwriter approach,” Ashcroft says today. “For me, I wanted to write concise stuff at that point. That opened up a well of material and melodies.”

Urban Hymns came together slowly, with The Verve cutting demos at Peter Gabriel’s Real World studios in Bath, and then with A Northern Soul producer Owen Morris, before the album sessions proper commenced with producers Youth (The Charlatans, Crowded House) and Chris Potter at London’s famous Olympic Studios in Barnes. At Richard Ashcroft’s instigation, string arranger Wil Malone (Massive Attack, Depeche Mode) was brought in and his swirling scores added a further dimension to a number of the album’s key tracks, including “The Drugs Don’t Work” and “Lucky Man.”

During these protracted sessions, The Verve expanded to a quintet after the estranged Nick McCabe was welcomed back into the fold. Among his arsenal of guitars, McCabe brought a Coral electric sitar and a Rickenbacker 12-string to the studio, and his spontaneity was encouraged as he added his inimitable magic to the guitars already precisely layered by Simon Tong. “What [Nick] did was very respectful,” Jones says today. “He made it all intertwine. He embellished what was already there and how it turned out was a beautiful thing.”

Assisted further by what Richard Ashcroft enthusiastically refers to as the “loose discipline” of Youth’s production methods, The Verve emerged triumphantly from the painstaking Olympic sessions knowing they had created music that would have a lasting impact.

“I knew the history of that room [Olympic Studio] and we were now a part of it,” Ashcroft recalls, speaking of the studio that had previously hosted the likes of The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix. “We’d hit a timeless seam. When Wil got those scores down, it was this incredible feeling that we could just hit Rewind and hear them again and again. It was like walking into a bank with millions and millions of pounds’ worth of music.”

The band’s self-belief was vindicated when Urban Hymns’ first single, “Bitter Sweet Symphony,” shot to No.2 in the UK in June 1997. Built around Malone’s strings and a four-bar sample from Andrew Loog Oldham’s orchestral rendition of The Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time,” the song was stamped with a timeless quality and soon gained further traction thanks to a memorable, MTV-friendly promotional film of Ashcroft walking down a busy London pavement, seemingly oblivious of anything going on around him.

With their star firmly in the ascendant, The Verve scheduled their first UK gigs for two years in September ’97, just as the album’s second single, the glorious orchestral swell of “The Drugs Don’t Work,” furnished them with their first UK No.1. Urban Hymns’ majestic trailer singles were inevitably singled out for praise when the album emerged, yet the record seamlessly ebbed and flowed between the band’s customary psychedelic wig-outs (‘The Rolling People’, “Catching The Butterfly,” the valedictory “Come On”) and expansive, existential laments such as “Space And Time’,” “Weeping Willow” and the elegant “Sonnet.” Barely a second seemed superfluous.

With Urban Hymns, which was released in all its glory on September 29, 1997, The Verve delivered the transcendent masterpiece they’d promised all along. With the critics onside (Melody Maker hailing the record as “an album of unparalleled beauty”) and fans unanimous in their praise, Urban Hymns not only knocked Be Here Now off the top of the UK chart (where it remained for 12 weeks), but also soared to No.12 in the US and went on to sell over 10 million copies worldwide.

Concerted acclaim followed, with The Verve scooping two Brit Awards in 1998, a coveted Rolling Stone cover, and a Grammy Award nomination (in the Best Rock Song category) for “Bitter Sweet Symphony.” Yet the magic the band alchemized was volatile at the best of times, and after The Verve split for a second time, in 1999, nine years elapsed before they returned to the fray and belatedly followed their masterpiece with Forth in 2008.

Released during a remarkable year for alt-rock, during which era-defining titles such as Radiohead’s OK Computer and Spiritualized’s Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space were also issued, The Verve’s Urban Hymns remains one of the most seminal albums of the 90s.

“I had 100 percent confidence it was going to be massive,” drummer Pete Salisbury recalls of this intense time. “Urban Hymns was a complete mix of where we were as a band. We were peaking.”

Proof, if it were needed: included in the album’s expanded six-disc edition is the band’s legendary homecoming show at Wigan’s Haigh Hall. A juggernaut performance in front of over 30,000 fans on May 24, 1998, it confirms what many have known for years: that The Verve circa Urban Hymns was a force of nature.

This article was first published in 2017. It’s being republished today in celebration of the release of Urban Hymns in 1997. The deluxe edition of Urban Hymns can be bought here.

erik giles

December 19, 2017 at 4:49 am

In Lucky Man, do I hear Joe Strummer subvocalizations in the intro?