Why ‘True Blue’ Ensures Tina Brooks Will Never Be Forgotten

The only LP that Tina Brooks released during his lifetime, ‘True Blue’ is a reminder that the saxophonist remains one of Blue Note’s unsung heroes.

Tina Brooks was a hard bop tenor saxophonist and composer who had the talent to go far in the jazz world but who never got his just desserts. Though he recorded four album sessions for Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff’s Blue Note label, only one was issued in his lifetime: True Blue.

Listen to True Blue right now.

Brooks was born Harold Floyd Brooks in 1942, in Fayetteville, a small town in North Carolina, and moved to New York with his family when he was 13. “Tina” was a corruption of “Teeny” – or “Tiny” – a nickname Brooks acquired when he was younger, denoting his diminutive stature. It stuck and followed him into adulthood. As a youngster, Brooks took up a C-melody saxophone in high school (getting tips from his older brother, who played tenor), before switching to, first, alto, and then tenor saxophone. His idols included saxophonist Lester Young but he served his musical apprenticeship playing in the R&B bands of Charles Brown and Amos Milburn during the late 40s and early 50s.

After a stint in vibraphonist Lionel Hampton’s group, Brooks was recruited by trumpeter Benny Harris. Impressed by the saxophonist’s adroit blend of technique and sensitivity, in 1958 Harris urged Blue Note’s Alfred Lion to give the young saxophonist a shot at recording. Lion obliged by arranging for Brooks to appear as a sideman with Hammond organ sensation Jimmy Smith on tracks recorded in February 1958 that eventually appeared on the albums House Party and The Sermon!. A month later, Lion gave Brooks the chance to record as a leader, when he took a stellar band comprising Lee Morgan, Sonny Clark, Doug Watkins, and Art Blakey into Van Gelder Studio to record his debut LP for Blue Note, Minor Move. For unknown reasons, the album wasn’t released, and it wasn’t until June 25, 1960 (by which time the saxophonist had appeared on another recording by Jimmy Smith and a session with guitarist Kenny Burrell) that Brooks recorded True Blue, an album that would write his name into the history books.

A gifted composer and fluid improviser

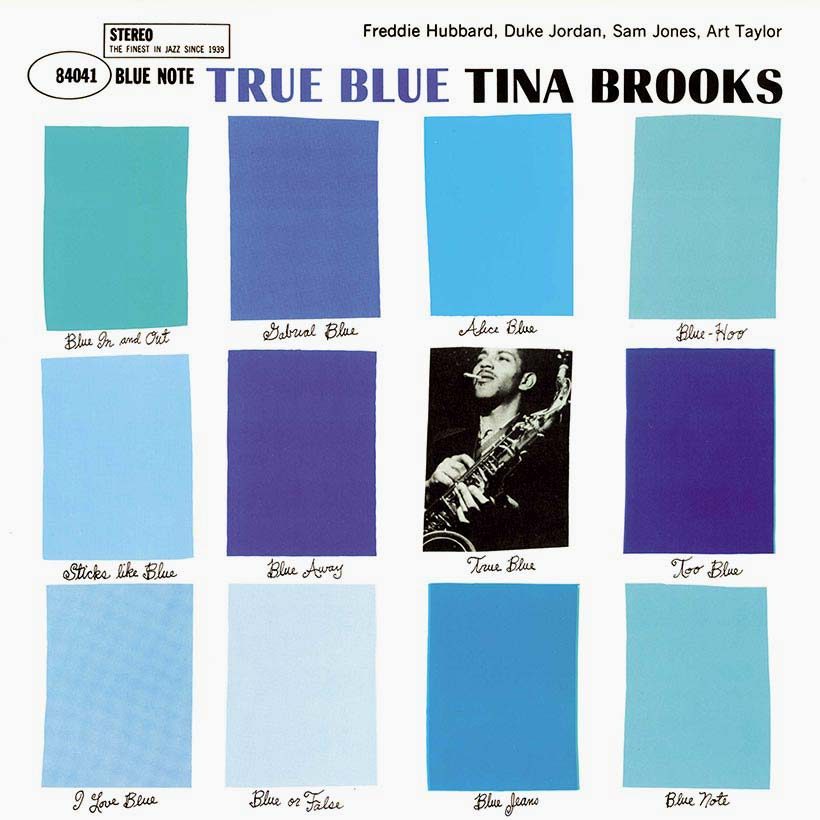

On True Blue, Tina Brooks, then 28, showed that he was a gifted composer as well as a fluid improviser by writing all six tracks. On the session he was joined by his young friend, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, then 24, whom he had met on a Count Basie session (Brooks also appeared on the session for Hubbard’s Blue Note debut, Open Sesame, recorded six days earlier, and wrote two songs for it, including the classic title cut). On True Blue, Hubbard is joined by pianist Duke Jordan, a former sideman for Charlie Parker and Stan Getz; bassist Sam Jones (then with the Cannonball Adderley group); and drummer Art Taylor, a ubiquitous session veteran whose credits at that point included sessions with Gene Ammons, Donald Byrd and John Coltrane.

A stirring clarion-call theme, played in unison by Brooks’ and Hubbard’s twin horns, announces the opening song, “Good Old Soul,” a mid-paced slice of finger-clicking hard bop. Brooks illustrates his prowess on the tenor saxophone with a long, snaking solo. He’s followed by Hubbard – whose dazzling passage of extemporization shows why the young horn blower from Indianapolis had taken the Big Apple by storm in the early 60s – and Duke Jordan, who plays with grace and economy.

More propulsive is “Up Tight’s Creek,” driven by Jones’ fast-walking bass, while the minor-key “Theme For Doris,” with its smoothly-contoured melodic line, is propelled by Latin-style rhythms. A harmonized melody distinguishes the jaunty title song. Like “Theme For Doris,” another song inspired by a female muse, “Miss Hazel,” is frenetic by comparison. The romantic-tinged closing cut, “Nothing Ever Changes My Love For You,” balances virtuosity with emotional expression over a simmering swing rhythm.

Though True Blue, now regarded as a hard bop masterpiece and one of Blue Note’s greatest ever albums, should have established Tina Brooks as an exciting new talent in jazz, it proved to be his swan-song as well as his debut. Three other sessions for Blue Note (one with altoist Jackie McLean) were also discarded and, after 1961, Brooks would never record again.

Thirteen years later, on August 13, 1974, the saxophonist died from liver failure at the age of 42. Though his time in the spotlight was tragically short, the enduring magnificence of True Blue means that Tina Brooks will never be forgotten.