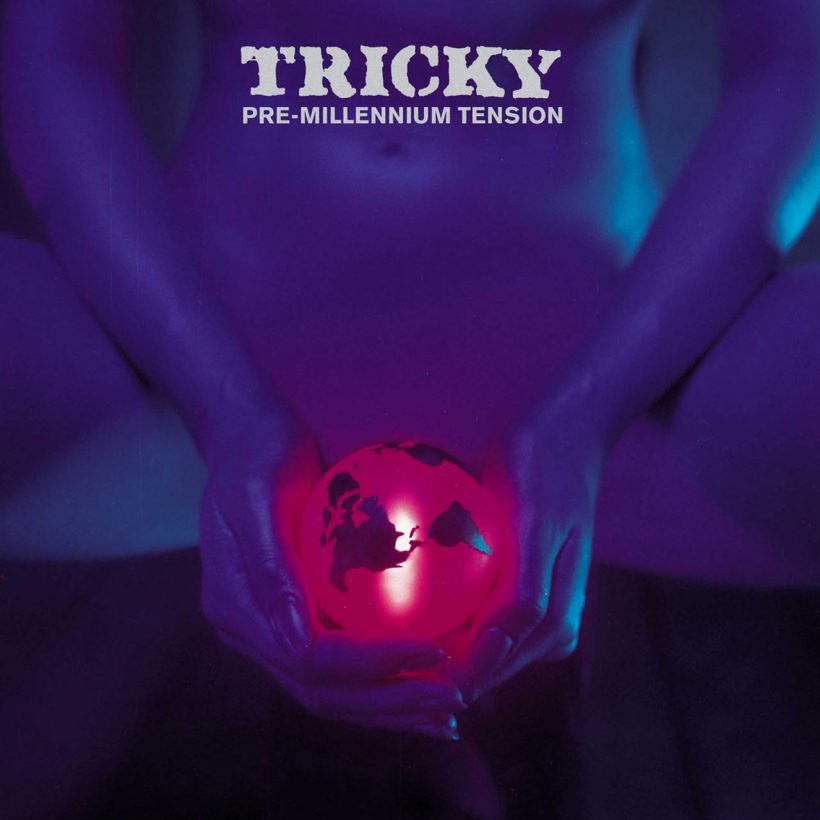

‘Pre-Millennium Tension’: How Tricky Challenged Expectations To Find Artistic Freedom

The Bristolian MC and producer’s second official solo album was a dark and defiant exploration of his inner psyche.

The odds were stacked against Tricky. Born Adrian Thaws in Bristol in January 1968, he grew up in Knowle West, one of city’s most deprived areas. His father, Jamaican sound system operator Roy Thaws, left home before he was born and at four years old, he lost his mother, Maxine Quaye, to suicide. He was raised by his grandmother and extended family against a backdrop of violence. In 2010, he told The Guardian, “I had seen my uncle stab my other uncle in the house when I was about six, seven. For a child, it’s not so much scary, it’s surreal.” As an adolescent he fell into crime and later spent time in prison after being caught in possession of forged £50 notes.

Music provided an escape – the joyful, political ska-punk of The Specials; the raw excitement of early hip-hop; the DIY attitude of punk rock and dub sound systems. He joined Bristolian hip-hop crew The Wild Bunch, who later became Massive Attack. His distinctive vocals – all West Country growls, whispers and murmurs – graced three tracks on the band’s landmark debut album, 1991’s Blue Lines. According to Tricky, when he decided to go solo, the group’s lynchpin 3D told him, “If you leave Massive Attack, you’ll never do anything. You can’t even get up in the morning. You’ll never make an album.”

Do you love 90s music? Buy the best 90s music on vinyl here or stream it on this playlist.

Tricky’s debut album, February 1995’s Maxinquaye, proved everybody who had ever doubted him wrong. The album, recorded in close collaboration with producer Mark Saunders (The Cure, Erasure, Neneh Cherry) and vocalist Martina Topley-Bird, sounded unlike anything else – a series of lush, off-kilter fever dreams in which disparate samples and genres cohere to create something uncanny and unique. It was an immediate hit, selling 100,000 copies in the UK in its first month and establishing Tricky as a generational talent. David Bowie wrote a gushing, stream of consciousness feature for Q magazine in which he imagined a conversation with the young upstart. And the establishment took notice – he was nominated for multiple Brit Awards and the Mercury Music Prize.

But success didn’t sit well with Tricky. Sick of the reductive ‘trip-hop’ label used to bundle him together with fellow Bristolians Massive Attack and Portishead, he moved to New York and set about making the music that spoke to him, resulting in a change of sound that would challenge expectations. “Maxinquaye sounds soft to me now,” he told NME in 1996. “But the industry makes you go this way. I couldn’t give a shit about Radio I and MTV. I’m not pop music. I can do pop music if I want, but it ain’t what I’m about.”

His next move was an album of deliberately unfinished demos released in February 1996 under the pseudonym Nearly God on his own Durban Poison label. Nearly God was a daring collection of bleak and brooding soundscapes studded with guest stars including Björk, Terry Hall, Neneh Cherry, Alison Moyet and Topley-Bird. It was warmly received, while many critics assumed it represented a clearing of the decks before Maxinquaye’s proper follow-up – little did they know what else he had up his sleeve.

Released in November 1996, Tricky’s official second album Pre-Millennium Tension was a bold and uncompromising reflection of where the rapper’s head was at. Though he could’ve worked anywhere, Tricky chose to record at the Grove Studios, Kingston, Jamaica, known as one of the city’s more rough and ready studios. Time away from the spotlight suited Tricky. “Going to Jamaica made me remember that I didn’t get into it for the money or the fame,” he told Touch magazine in 1997. “In England, Island Records told me from the beginning ‘you can do anything you want’ so obviously I did anything I wanted. You just get your ego stroked all the time. In the studio in London, you can say ‘make me a cup of tea, get me some food, roll me a spliff’. In Jamaica if I asked them to get me a tea they just said ‘bloodclaat get it yourself’. I had to make my own tea, buy my own weed, it stops you being lazy.”

The opener “Vent” quickly establishes Tricky’s intentions. Over skittering beats, distorted bass riffs and clanging machine noise, he croons and wheezes, quoting Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message” (“Don’t push me, ’cos I’m close to the edge, I’m tryin’ not to lose my head”) before Topley-Bird enters, sweetly crooning “Can’t hardly breathe” repeatedly as the song descends into chaos around her. Tricky had struggled with severe asthma since he was a child (in the documentary Naked And Famous, his grandmother claims he suffered his first attack on hearing about his mother’s death) and was increasingly suffering from the side effects of medication. In May 1998, he’d be diagnosed with candidiasis, a personality-altering fungal infection brought about by excessive use of asthma medication – “Vent” gives the listener an idea of how the illness had affected him.

“This is not a coffee table album. I don’t think you can have dinner parties to it,” Tricky wrote in Pre-Millennium Tension’s press release, responding to the reputation of Maxinquaye. His claim is not only backed up by “Vent” but by the tough, dub-infused “Ghetto Youth” (which features Sky, a local Tricky had befriended freestyling in patois); the coruscating and disorientating “Sex Drive”; the warped and juddering “My Evil Is Strong”; and the dread-filled closer “Piano.” Elsewhere, his early love of hip-hop and the influence of his new home came to the fore. Looking back, he told Vice in 2016, “The reason I moved to New York was due to loving hip-hop and considering myself a b-boy. And I always knew that one day I would have to live in New York. That was the mecca… That was where I was coming from, and the reason I arrived to New York, which was to link up with hip-hop artists.”

Tricky’s debt to hip-hop was made explicit on one of Pre-Millennium Tension’s highlights, the thrilling “Tricky Kid”, a song that had appeared on the compilation EP Tricky Presents Grassroots he’d released in August ’96. Over a heavy, swaggering beat Tricky spits braggadocio, his throat sounding ravaged as he vents against pale imitations of his style. Elsewhere, just as he and Topley-Bird had put a unique spin on Public Enemy’s “Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos” on Maxinquaye, here they reworked classic hip-hop tracks with versions of Chill Rob G’s “Bad Dreams” and Eric B & Rakim’s “Lyrics Of Fury.”

Meanwhile, a brace of songs – the laid-back groove of “Christiansands” and the slinky “Makes Me Wanna Die” – offer moments of reflection and even blissed-out beauty, Topley-Bird’s vocals offering a vulnerable contrast to Tricky’s gravelly mutterings. Pre-Millennium Tension was a sketchy, innovative and fascinating album that gave genuine insights into the mindset of a unique artist. It’s by no means an easy listen, but over the years its grit and nuances have won over countless music fans. After Maxinquaye, Tricky could’ve taken the easy option and chosen more fame and money, decades later, his instincts have been proved correct.

“When I started touring, actual fans would come up to me with Pre-Millennium Tension saying, ‘I was in a coma for 10 days and this album saved my life,’ or ‘I work in a kids’ burn unit and this album helps me cope,’” he later told Vice. “You’ve got to realize that success is all kind of an illusion, or at least what we consider success. Maxinquaye comes out in England and it’s at the Top of the Pops, and you would consider that success. But Nearly God and Pre-Millennium Tension were much darker albums.” He’s not looked back since.