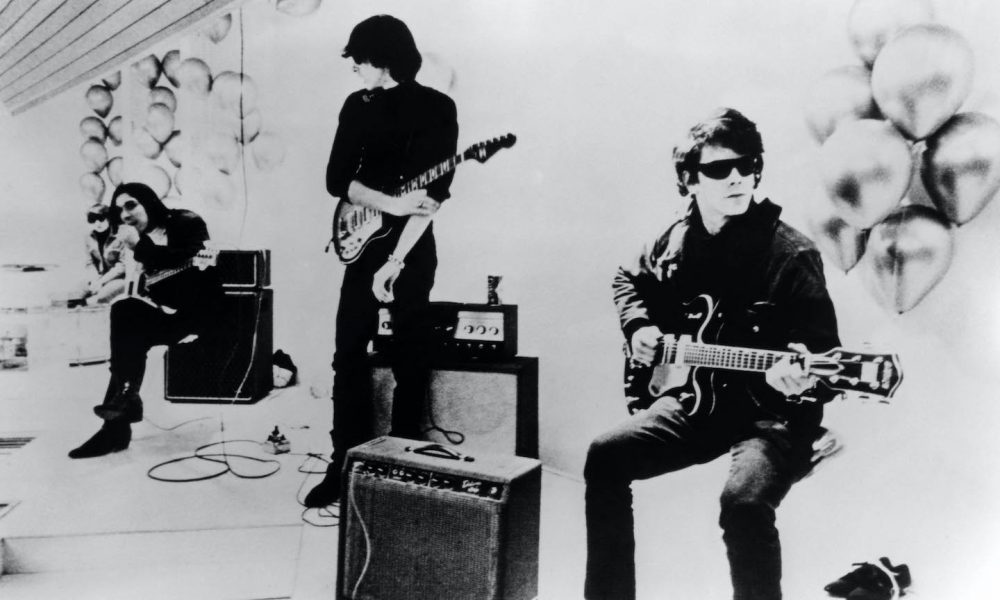

Tracing The Influences Of The Velvet Underground

These are the inspirations that empowered The Velvet Underground to trash rock’n’roll tropes and replace them with the sound of the future.

The Velvet Underground spent the second half of the 60s gleefully stomping conventional rock concepts to smithereens and fashioning the shards into something shockingly new. But even they weren’t born in a vacuum. Equally informed by the seamy side of NYC bohemia and the comparatively lofty realms of literature and experimental music, the Velvets built a world where sexual taboos, illicit substances, and street-level decadence intertwined with modernist poetry, deliberate dissonance, and calculated musical minimalism. The result was one of the most influential sounds in rock history, prefiguring punk, alternative, and more. But what were the inspirations that empowered The Velvet Underground to trash rock’n’roll tropes and replace them with the sound of the future?

Composer La Monte Young

John Cale was a classically trained musician, but before venturing into rock by forming The Velvet Underground with Lou Reed, he was in an even more uncompromising, iconoclastic ensemble. He played viola in the Theatre of Eternal Music, led by avant-garde godhead La Monte Young, and the ideas he onboarded from their minimalist drone manifestos helped forge the Velvets’ sound. “We were digging into all sorts of things,” Cale told Red Bull Music Academy, “intonations, tonality…. some of it was, musically speaking, a breakthrough.” Cale’s monomaniacal viola on “Black Angel’s Death Song” is one of many minimalist-motivated Velvets moments.

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s novel Venus in Furs

Lou Reed was fascinated by the idea of assimilating literature into the rock’n’roll bloodstream, especially if there was a transgressive tinge to it. Venus in Furs is an 1870 novel by Austrian nobleman Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, and the fact that masochism is named after him should give you a clue about the content. Reed picked it up and pounded out a song about it, with Cale’s viola drone lending decadent color, but titling the song after the book still didn’t keep early critics from assuming it was some sleazy Reed fantasy. “They didn’t even know ‘Venus in Furs’ was a book,” he said, “I didn’t write it, I just said it would be interesting to take this book and put it in a song.”

Click to load video

Poet and writer Delmore Schwartz

Before Reed emerged from academia to reinvent rock, he was already being schooled in stylish subversiveness by his professor Delmore Schwartz, a New York poet and short story writer who’d begun building his legend in the 1930s with books like In Dreams Begin Responsibilities. “What he could do with five words was astonishing to me,” exclaimed Reed. “He had an advanced vocabulary, but he could also write the simplest things conceivable and there would be such beauty in them.” Reed dedicated the elliptical thunderbolt “European Son” from the VU’s debut to Schwartz, and it wouldn’t be his last tribute to his teacher.

Doo-wop music

In 1966, before The Velvet Underground even released their first album, Reed wrote the essay, A View from the Bandstand, for an Andy Warhol-edited issue of Aspen magazine, extolling the doo-wop of groups like The Harptones and The Jesters. Proving Cale wasn’t the only one with an ear for minimalism he praised what he saw as the music’s repetitive, reductive beauty, and declared, “The only decent poetry of this century was that recorded on rock-and-roll records,” observing, “You can get high on the music, straight.” The dreamy flow and wordless vocals of “I Found a Reason” from Loaded, and the blend of unironic teen-romance lyrics with call-and-response harmonies on “There She Goes Again” handily drive Reed’s love of doo-wop home.

Click to load video

Drugs

There’s no getting around the debt Lou Reed’s early songs owed to mid-altering substances, whether he was writing as an observer of or a participant in 60s drug culture. Before Reed unleashed his poetic portrait of opiate addiction on “Heroin” and his hardscrabble account of a junkie copping in Harlem on “Waiting for the Man,” nobody had ever dealt so unabashedly with the topic in songs of any genre. By the time he unleashed the epic “Sister Ray” on White Light/ White Heat, he was delivering an almost campy depiction of a cross-dresser heroin dealer’s world.

Andy Warhol’s world

Besides being the Velvet Underground’s manager, mentor, and nominal producer, Andy Warhol influenced the band just by putting them in the middle of his wonderfully weird world. The actors, models, photographers, and other artists embedded in Warhol’s exclusive multimedia hub The Factory became unexpected muses. “All I did was sit there and observe these incredibly talented and creative people who were continually making art and it was impossible not to be affected by that,” said Reed. The tender, transcendent “Candy Says,” inspired by the angst of trans actress Candy Darling, is only one timeless example.

Click to load video

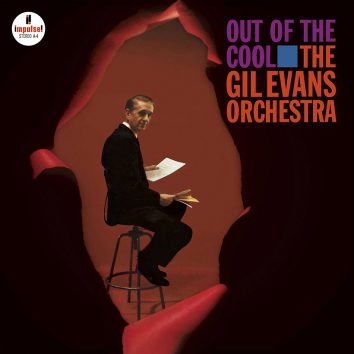

Free jazz

Like a lot of Lou Reed’s passions, his fondness for avant jazz went back to his college days, when he had a show on the Syracuse University radio station named after piano trailblazer Cecil Taylor’s “Excursion on a Wobbly Rail.” It’s not difficult to spot the spirit of free jazz on the more unconstrained side of the Velvets’ canon, like the aforementioned 17-minute rager “Sister Ray.” “I had been listening to a lot of Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman,” Reed explained to Lester Bangs in Creem, “and wanted to get something like that with a rock & roll feeling.”

The tribute record, I’ll Be Your Mirror: A Tribute to the Velvet Underground & Nico, is out on September 24 and available for pre-order.