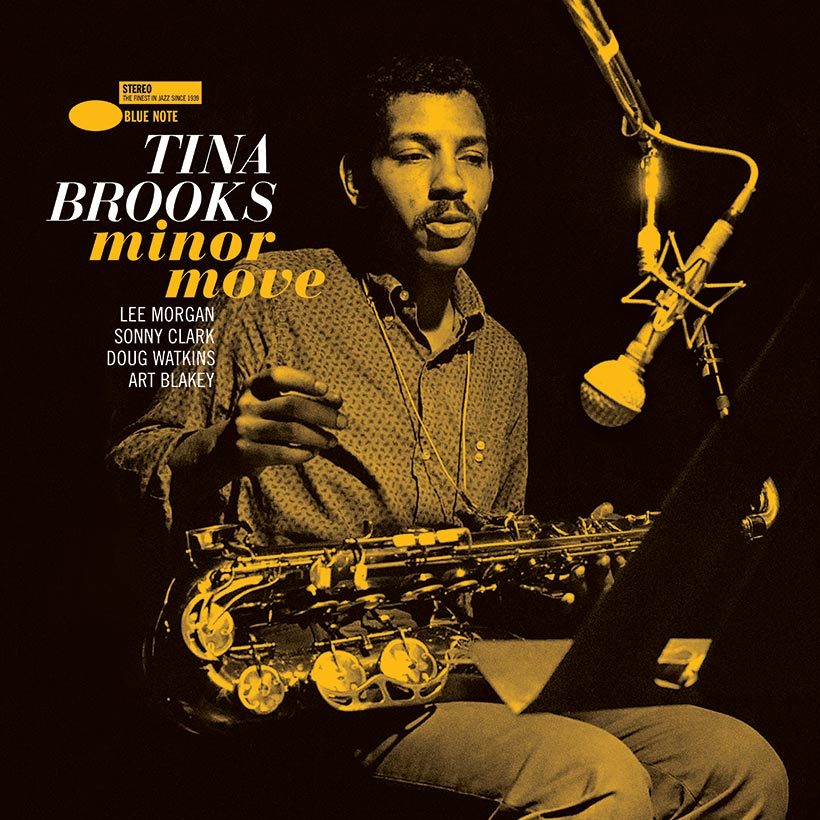

‘Minor Move’: A Major Revelation In Tina Brooks’ Life

Shelved after its original recording, ‘Minor Move’ was saxophonist Tina Brooks’ debut recording as a bandleader for Blue Note. It sounds revelatory today.

Harold “Tina” Brooks’ life and career fits one of those classic what-might-have-been scenarios. He began recording for Blue Note Records, initially as a 25-year-old sideman for organist Jimmy Smith, in March 1958. Impressing the label’s boss, Alfred Lion, he was given a shot as a bandleader, recording the noteworthy album True Blue in 1960. After 1961, however, Brooks – who had also played with Kenny Burrell, Freddie Hubbard, Jackie McLean, and Freddie Redd – never recorded another note. He eventually disappeared from the New York jazz scene altogether, as heroin addiction, the scourge of many a jazz musician in the 40s, 50s, and 60s, took its toll. On August 14, 1974, Brooks was dead, aged 42, his work at Blue Note a distant memory. In the jazz public’s eyes, the doomed saxophonist was just a one-album wonder who had never reached his potential. Little did they know that a number of albums sat in the vaults, just waiting to be discovered; among them was his first-ever session as a bandleader, Minor Move.

Listen to Minor Move on Apple Music and Spotify.

Producer Michael Cuscuna’s discovery, during the latter half of the 70s, of previously unreleased Brooks album masters in the company’s vaults warranted a complete revision of Brooks as a musician. Recorded on the afternoon of Sunday, March 16, 1958, at Van Gelder Studio in Hackensack, New Jersey, Minor Move documents what happened when Alfred Lion assembled a quintet to showcase Brooks’ talent.

Stellar company

The line-up for the session consisted of a 19-year-old trumpet prodigy called Lee Morgan – by then already a veteran of Blue Note recording sessions, having signed to the label in 1956 – alongside rising hard bop pianist Sonny Clark (also signed to Blue Note), bassist Doug Watkins, and a 39-year-old drummer, Art Blakey, whose day job was leading the successful hard bop group The Jazz Messengers. It was a fine ensemble that married youth with experience and, judging from Brooks’ performances, the young man who was born in North Carolina, on June 7, 1932, wasn’t fazed by such stellar company.

Minor Move opens with “Nutville,” the first of two original tunes on the five-track album. It’s a midtempo blues built on a lightly-swinging undertow propelled by Watkins’ firm walking bassline and Blakey’s in-the-pocket drum groove. After a harmonized head theme played by the horns, the drummer’s signature press roll introduces the first solo, by Lee Morgan, who demonstrates his total command of his horn with lithe runs and clever flourishes. Another Blakey press roll is the cue for Morgan to lay out and Brooks to take center stage; he confidently obliges by delivering a long, snaking tenor solo that’s by turns muscular and lyrical. All except Blakey drop out to allow Doug Watkins to reveal his bass prowess in a short passage before the head theme is reprised.

The Jerome Kern-Dorothy Fields standard “The Way You Look Tonight” is often played as a ballad, but Brooks’ version transforms the song into an energetic hard bop swinger with fine solos from all the participants. Brooks is particularly impressive with the fluidity of his playing as melodies spill from his horn in liquid phrases.

Top-drawer playing and a natural elegance

Another standard, “Star Eyes” (co-written by Gene DePaul, author of another fine evergreen, “Teach Me Tonight”) was often used as a vehicle for improv by the great bebop altoist Charlie Parker. Here, Brooks and his confreres attack the tune at a brisk tempo, with Morgan using a mute at the piece’s beginning and end. After Brooks’ solo, Sonny Clark shows why he was so highly regarded as a pianist. More top-drawer playing comes from Lee Morgan, whose horn phrases are alternately cool and florid.

The start of Minor Move’s title track, a Brooks original, exudes a Latin feel with its harmonized twin horns riding on a syncopated Blakey groove driven by tinkling ride cymbals and featuring Clark’s laconic piano punctuations. The song morphs into a crisply-paced swinger driven by Watkins’ walking bass during the solo passages. Brooks pours out molten phrases, followed by Morgan, whose declamatory approach is almost brash. Sonny Clark’s piano solo, by contrast, evinces a natural elegance as it glides over Watkins’ and Blakey’s simmering rhythms.

“Everything Happens To Me” is Minor Move’s only slow ballad. Sonny Clark’s understated piano sets the scene, laying a solid foundation for Brooks’ subdued but sure-footed and smoky tenor saxophone lines. Watkins plays with both precision and economy while Blakey, usually renowned for his bombast and power, keeps the rhythmic pulse beating quietly and unobtrusively in the background. The song ends with a lovely tenor saxophone cadenza by Brooks.

We’ll never really know why Minor Move was left on the shelf alongside the other posthumously released Brooks sessions, Street Singer, Back To The Tracks, and The Waiting Game. Thankfully for jazz fans, when Michael Cuscuna heard it, he granted the album a release, and it was issued for the first time by King Records in Japan, in 1980. Minor Move later appeared on CD for the first time in 2000 as part of Blue Note’s limited edition Connoisseur series.

Now, decades later, the album has been lovingly mastered from Rudy Van Gelder’s original two-track master tape by Kevin Gray under the supervision of producer Joe Harley, getting a new lease of life via Blue Note’s acclaimed Tone Poet Audiophile Vinyl series. Its revival will prove that Tina Brooks was a major, not a minor, tenor saxophonist.