The Women of Stax: Five Unheralded Pioneers

At a time when the music business was dominated by men, the Memphis soul label Stax Records employed a host of women in key positions.

In the mid-20th century, the music business was dominated by men – particularly when it came to creative and corporate roles at labels and recording studios. And while there were trailblazers in these fields – including songwriters Dorothy LaBostrie and Carole King, session musician Carol Kaye, producer Ethel Gabriel, and entrepreneurs like Cordell Jackson, who established Moon Records in 1956, – these women were the rare exceptions.

One outlier in the industry was Stax Records. Beginning with its co-owner, Estelle Axton, Stax Records employed women in a number of essential positions throughout its heyday. Yet, while many can name the highly-successful women on the Memphis label’s roster – including Carla Thomas, Mavis Staples, Jean Knight, and The Emotions – few know about the ladies behind the scenes. Below are some of the inspiring women who helped Stax become a soul powerhouse.

Listen to the best of Stax Records on Apple Music and Spotify.

Estelle Axton

In the late 50s, Estelle Axton was living in suburban Tennessee, raising two children and working in a bank, when her younger brother, Jim Stewart, raised the idea of starting a record label. Recognizing the potential of the fast-growing industry, the business-savvy Axton convinced her husband to remortgage their home to help fund the business. In 1959, as equal partners, the siblings turned a shuttered Memphis theater into a small record shop, label, and studio. Initially established as Satellite Records, the two later combined their last names to form the name Stax.

Finding great pleasure in her new role at Stax, Axton quit her job at the bank to focus on developing the label, using the record shop as a way to discover new trends and to better understand why certain titles sold more than others. She and Stewart then used that insight to dictate the output of their own artists.

Estelle Axton; photo courtesy of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Axton was instrumental in signing and developing many of the label’s early acts – including Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, and Rufus and Carla Thomas. And while her work at Stax certainly had a profound impact on popular music, Axton also served another important role. As a Southern white woman, she was breaking racial barriers when segregation was still in full effect. At Stax, both white and Black people worked together as equals, whether in the studio or at the label’s offices. Quoted on the Stax Museum of American Soul Music’s website, Axton once declared, “We never saw color, we saw talent.”

In Axton’s obituary in The Guardian, Stax star Isaac Hayes elaborated, “You didn’t feel any back-off from her, no differentiation that you were Black and she was white…Being in a town where that attitude was plentiful, she just made you feel secure. She was like a mother to us all.” That sentiment – of Axton being an encouraging, mother-like figure – was echoed by many of Stax’s staffers and artists over the years.

While Axton sold off her share of the label in 1970, she remained a powerful force in the Memphis music scene. In 2012, her work was recognized with a posthumous induction into the Memphis Music Hall of Fame.

Bettye Crutcher

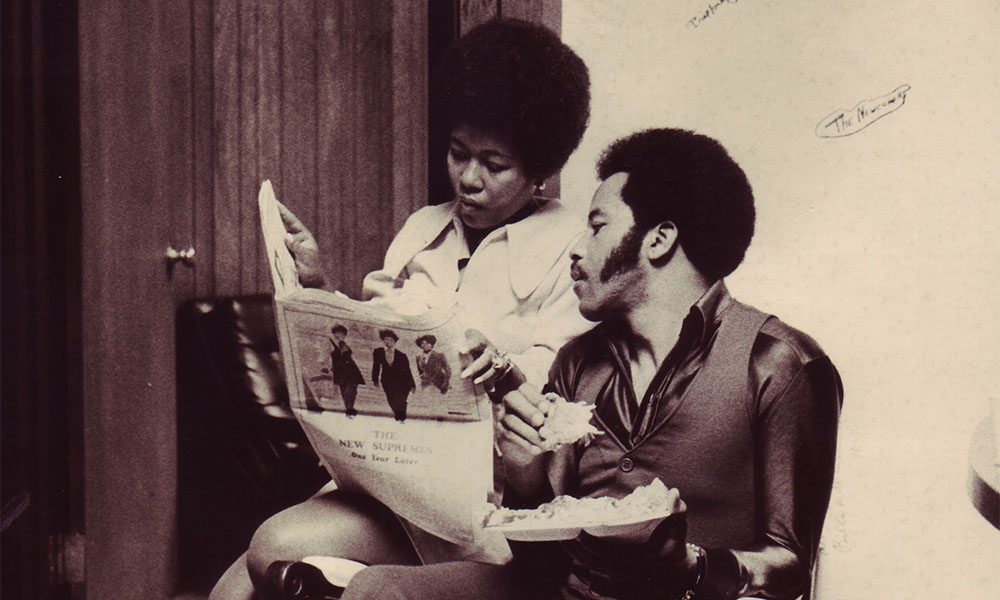

Until Bettye Crutcher joined the in-house songwriting team at Stax in 1967, much of the writing for the label was handled by the hitmaking team of David Porter and Isaac Hayes, whose joint credits included songs like Sam & Dave’s “Hold On, I’m Comin’” and “Soul Man,” and Carla Thomas’ “B-A-B-Y.”

Things changed when the 20-something Crutcher auditioned for Porter. While the Memphis native – who had written poems and songs since her youth – always considered the craft to be more of a hobby, Porter was struck by her talent and hired her on the spot.

In an interview with Soul Express, Crutcher recalled, “[Porter] said ‘I really like the way your songs are structured, but you’re gonna have to write songs that work for our artists here at Stax. Well, he shouldn’t have told me that (laughing), because I went and wrote a song for Johnnie Taylor. They had been looking for songs for him, but nobody could come up with anything that really suited him or his style…”

Crutcher clearly loved a challenge. Along with fellow writers Homer Banks and Raymond Jackson, she helped Taylor score his first No.1 R&B hit, “Who’s Making Love.” The song, which peaked at No.5 on the Billboard Hot 100, also earned Taylor a Grammy nod. The writing trio (known as We Three) followed with “Take Care of Your Homework” – a No.2 hit for Taylor on the R&B chart, as well as with Carla Thomas’ Top Ten R&B single “I Like What You’re Doing To Me.”

During her tenure at Stax, Crutcher wrote or co-wrote hundreds of songs for the label’s biggest acts, including The Staple Singers, Sam & Dave, William Bell, Booker T. & The M.G.’s, Albert King, Shirley Brown, Etta James, The Mad Lads, The Temprees, and The Sweet Inspirations, among many others. In those years, the prolific writer also found time to record her one and only solo album, 1974’s Long As You Love Me (I’ll Be Alright).

Crutcher’s talents were recognized far beyond the Stax orbit. In Robert Gordon’s book Respect Yourself, Crutcher recalled a particularly meaningful moment in her career, which took place at the 1968 BMI Awards. “I was receiving [an award]…and John Lennon was receiving one too…I wanted so much to meet him, but I found that he wanted to meet me. I bet I was ten feet tall when I left that presentation. It said that somebody was listening to what I wrote.”

Mary Peak Patterson

In 1972, Stax executive Al Bell sought to expand the label’s roster and break into the emerging gospel market. He established the imprint Gospel Truth, enlisting radio promotions pioneer and songwriter Dave Clark to oversee the label, alongside Stax staffer Mary Peak Patterson.

This was a life-changing moment for Peak Patterson, whose professional goals laid far beyond the realm of an administrative position. And the timing couldn’t have been better – Peak Patterson was on the verge of quitting her job in Stax’s creative department to pursue a career as a real estate agent when she was offered the lofty role. “I was never interested in working for somebody. I knew that was not the way to go,” she told journalist Jared Boyd in the liner notes to The Complete Gospel Truth Singles.

Together, Peak Patterson and Clark reinvented the genre – making it hip, stylish, and accessible to all. In the words of a promotional pamphlet, their goal was to carry “the message of today’s gospel to the people on the street.”

While Clark signed new acts (including the Rance Allen Group, Louise McCord, and Joshie Jo Armstead), Peak Patterson handled the artists’ bookings, aided in management, and oversaw many of the promotional considerations. It was the latter detail that set Gospel Truth’s groups apart. Peak Patterson ensured that the imprint’s rising acts were given the same promotional opportunities that Stax’s secular artists were – including wardrobe budgets, backing groups, press campaigns, stylish visuals, and bookings in concert halls and clubs – rather than in churches.

Although Gospel Truth folded in 1975 when Stax declared bankruptcy, Peak Patterson’s ambition helped shift the genre into the multi-million-dollar industry that it has become today.

Peak Patterson’s mission can best be summed up in the announcement materials that she wrote for Gospel Truth’s launch: “We feel that gospel music is an integral part of our heritage, and The Stax Organization is conscious of its responsibility to bring the new gospel to a larger stage. Our goal is to keep the message strong and pure while adding to its potency, by presenting it within the framework of present-day rock. It then becomes identifiable and important. After all, it really doesn’t matter if you listen to gospel quietly, snap your fingers, sing along, or dance to it, as long as you get the message.”

Earlie Biles

In 1968, as Stax was rapidly expanding, Al Bell hired Earlie Biles as his executive assistant. At 21, Biles had no experience in the music industry – and no idea what she was getting herself into. In Respect Yourself, Biles recalled being shocked to see Isaac Hayes walking through the halls “with no shirt, some thongs, and some orange-and-purple shorts.” She also remembered having to store a producer’s gun in her desk drawer…because his pants were too tight to conceal it.

In spite of all this, Biles found herself becoming an essential asset to the team, as the label’s output – and profits – soared. Biles helped to put much-needed procedures in place to ensure that the label ran efficiently, and served as a gatekeeper for the overburdened Bell.

But Biles’ professional ingenuity often crossed over into her personal life. Biles, who lived next door to Bell, told Gordon that “When [people] couldn’t get through to see [Bell], they would wait in the parking lot…[or] they’d go to his house.” She recalled numerous sleepless nights when she and her husband would have to chase down people “who tried to get to Al by throwing pebbles at his window.”

In the label’s chaotic, final days, Biles remained loyal to Bell and Stax, even while looking out for her own future. In Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records, author Rob Bowman noted that when Biles enrolled in law school in Southern California, her allegiance “was so great that she attended school from Monday through Thursday, then flew back to Memphis, charging the plane tickets to her own credit card, worked at Stax over the weekend, and flew back to Inglewood for class on Monday.”

Deanie Parker

In 1963, Deanie Parker won an opportunity to audition at Stax after winning a local talent contest. The promising singer-songwriter was offered a contract, but she quickly found that her interests lay in a behind-the-scenes role. Parker, who was studying journalism in college, proposed the idea of becoming the label’s publicist. Jim Stewart agreed, and thus began Parker’s long – and vital – association with Stax.

Over the next 11 years, Parker held a variety of roles within the label – including songwriter, arranger, liner note writer, and photographer. As Stax’s sole publicist, she not only communicated the label’s activities to the media but also kept fans informed with the Stax Fax newsletter.

But Parker’s role after Stax closed its doors was just as crucial. At the turn of the millennium, Parker led efforts to build the Stax Museum of American Soul Music on the grounds where the label and studio originally stood. She became the president and CEO of Soulsville – a nonprofit organization that oversees the museum, as well as the Stax Music Academy, the Soulsville Charter School, and the Soulsville Foundation, which seeks to perpetuate “the soul of Stax Records by preserving its rich cultural legacy, educating youth to be prepared for life success, and inspiring future artists to achieve their dreams.”

For more, listen to our exclusive interview with Ms. Parker here. Thanks to her incredible efforts, the trailblazing spirit, and enduring music of Stax, will continue to live on for generations to come.

Listen to the best of Stax Records on Apple Music and Spotify.