10 Things We Learned From ‘The Velvet Underground’ Documentary

Todd Haynes’ new film explores the Velvet Underground’s story, stitching it into an intoxicating tapestry with the avant-garde film, art, writing, and music that were part of the band’s transgressive milieu.

“We didn’t expect to sell records,” said Lou Reed about the Velvet Underground. “That’s not what we were doing.” Probably no other band has had such a drastic disparity between initial reception and posthumous notoriety, and more than 50 years after their final album, it’s finally time for a major Velvet Underground documentary.

The last time director Todd Haynes tackled an American musical legend, he redefined the musical biopic with 2007’s I’m Not There, his leftfield look at Bob Dylan’s legacy. So Haynes seems like the ideal auteur to document the most unconventional rock legends of the 60s in The Velvet Underground.

Interviewing surviving members John Cale and Maureen Tucker along with tons of the band’s intimates, influences, peers, and proteges, Haynes gets the inside scoop on the Velvet Underground’s story, stitching it into an intoxicating tapestry with the avant-garde film, art, writing, and music that were part of the band’s transgressive milieu. In the process, some annals are amplified, others debunked, and new ones unveiled. Here are just a few of the juicy tidbits revealed in The Velvet Underground.

Listen to the official soundtrack to The Velvet Underground, out now.

1. A pre-Velvet Underground John Cale made America laugh on TV

In 1963 the Velvet Underground co-founder was deeply embedded in the avant-garde music scene. An epic John Cage-produced performance of Erik Satie’s Vexations (comprised of a simple phrase repeated 840 times) earned Cale an appearance on TV game show I’ve Got a Secret, where celebrity guests had to guess his distinction. He even did a brief demonstration on the studio’s piano, but early-60s American TV viewers weren’t ready for minimalist musical concepts. Despite his unstinting earnestness, Cale ultimately inspired only titters of nervous laughter from the studio audience.

2. Lou Reed was already making records at 14

In the 50s, Lou Reed was a teenage rock’n’roller, living on Long Island and working with a band called The Jades. At 14, guitarist and backup singer Lou (then billed as Lewis) wrote the B-side to the band’s only single, a doo wop-tinged stroll that features R&B giant King Curtis on sax. “We got a royalty check for $2.79,” remembered Reed of his first-ever recording. “Which in fact turned out to be a lot more than I made with the Velvet Underground.”

3. John Cale killed his classical career with an ax

Another 1963 avant-garde dust-up for John Cale came when he performed a piece of his own at legendary Massachusetts classical venue Tanglewood. The audience was full of people a young composer would want to impress, like Olga Koussevitzky, widow of composer and Tanglewood bigwig Serge Koussevitzky. The piece ended with Cale taking an ax to the piano. “I remember that one of the people in the front row got up and ran out,” he says in the film, “and that was Mrs. Koussevitzky, she was in tears.” The classical music mainstream was clearly a less than glove-tight fit for Cale.

4. Lou Reed and John Cale tried to start a dance craze

When Reed and Cale first hooked up they had a band called The Primitives and cut a single called “The Ostrich” for the low-budget label Pickwick, where Reed was still employed as a staff songwriter. Reed allegedly created a custom-made tuning for the track that involved tuning every string to the same note. Listeners were commanded to “do The Ostrich,” with instructions like, “Put your head between your knees.” It didn’t exactly become the next Twist, but the Velvets reportedly adopted the tuning for slightly less danceable songs like the S&M saga “Venus in Furs” and “Heroin.”

5. The first real Velvet Underground tour was a train wreck

The Velvets eventually built up a reputation in New York, but in mid-1966 they toured as part of their manager/producer/mentor Andy Warhol’s experimental multi-media extravaganza The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, an experience encompassing music, film, dance, and light show. “There were so many times when we’d play some kind of art show and they’d invited Andy and we were the exhibit,” laughs Tucker in the film. “They’d leave in droves, these were rich society people and artists and stuff, and they didn’t want to hear a band, let alone what we were doing.”

6. Bill Graham hated their guts

There wasn’t much West Coast love for the Velvets either, especially not from Bill Graham, promotional patron saint of the psychedelic scene. Remembering their 1966 shows with Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention at Graham’s famed Fillmore West venue, Tucker says, “Boy, he hated us. When we were going onstage he was standing there and he said, ‘I hope you f__kers bomb.’ I think he was really jealous and pissed off because he has claimed to have the first multi-media, and it was pitiful compared to what Andy had put together.”

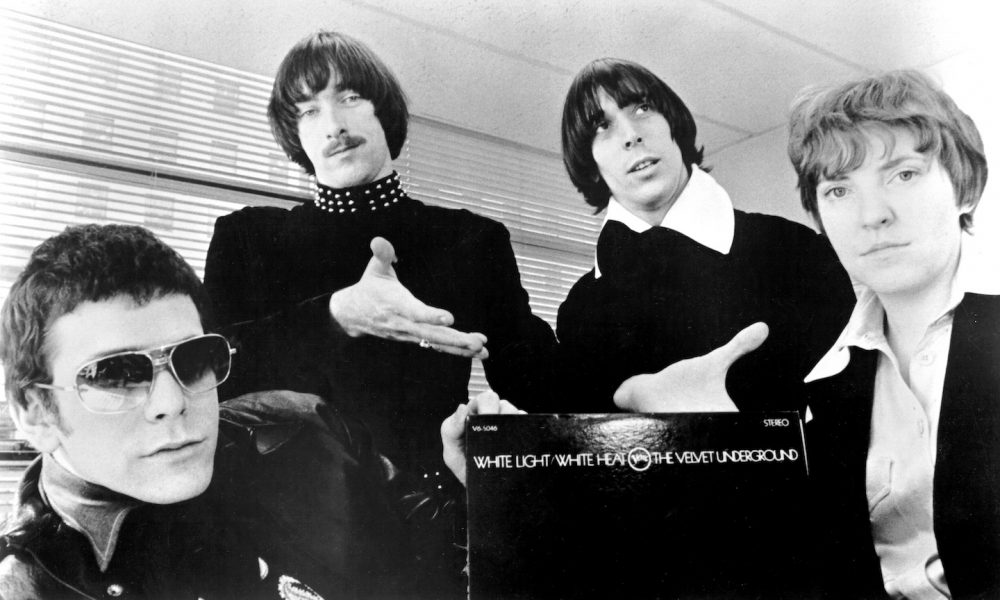

7. Their engineer abandoned them

When the band was recording its ultra-aggressive second album, White Light/White Heat, in 1967 (described by Cale as “totally aggro”), the sonic intensity even alienated the Velvets’ own engineer. “The engineer left,” remembered Reed. “One of the engineers said, ‘I don’t have to listen to this. I’ll put it in ‘record’ and I’m leaving. When you’re done, come and get me.’”

8. Jonathan Richman was both a superfan and protégé

The Velvet Underground built up a following in Boston, and years before founding The Modern Lovers, Jonathan Richman was at its core. “I saw them a total of about 60 or 70 times,” he says. “I was hearing this music that I realized sounded like nothing else. Not only was it new but it was radically different.” But his experience became much more interactive. “Sterling Morrison was the one who taught me to play guitar,” Richman reveals. “The freedom of it made me feel less tied to high school, less tied to any conventions that other music had, and helped me figure out how to make my own music.” The wide-eyed kid was taken under the band’s wing. “They were certainly generous with me,” he says, “they let me open a show for them once.”

9. Moe Tucker was terrified to sing ‘After Hours’

Saying that audiences would “believe her where they wouldn’t believe me,” Reed brought Moe Tucker out from behind the drums to sing the tender-hearted ballad “After Hours” on the band’s self-titled third album. “I was scared to death,” says Tucker. “I’d never sang anything and I was really like, ‘I can’t do this.’ In fact, we had to send Sterling [Morrison, guitarist] out of the room because he was laughing at me.” She dreaded singing it in concert too, but Jonathan Richman remembers a Boston show where, “People who weren’t even fans of the band much that night… Maureen Tucker would come out and… she’d get everybody.”

10. Lou Reed quit the band at Max’s Kansas City

Max’s Kansas City in New York was home turf for the Velvets, but it was also the site of their undoing. By 1970, the band’s continued Sisyphean struggle for success had pushed Reed to the breaking point. It all came to a head at an August 23 show at Max’s. Influential music manager and Warhol pal Danny Fields recounts, “I had gone to see them at Max’s and the set was over and Lou came towards the exit. I said ‘Oh, Lou,’ and he just kept walking really fast. And then someone said, ‘He just quit the band’… that’s it. It’s over.” At least that last show was captured for posterity on the posthumous, now-classic album Live At Max’s Kansas City.

Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Underground is available to stream on Apple+ TV.

Jymn Parrett

March 24, 2022 at 8:24 am

This is a disappointing film, shot by a director who is more interested in his own style than substance. The things learned from the film are few and far between, nothing that even a casual VU fan would already know. It’s really a vanity project, like most of Haynes’ films, more about him than his subjects. You never get the feel of what it was like at the time. The viewer ends up as a viewer and not feeling part of the experience. It’s purely intellectual and the Velvet Underground were much more than just about the intellect.