Sounds Of Science: The Electronica Pioneers You Never See

A celebration of the visionary tech pioneers whose work still has the ability to shock, thrill and perturb.

In much the same way that a cherished love song seems to uncannily mirror one’s own experiences, circumstances, or desires, abstract electronica can replicate feelings of mild unease, mortal dread, or awestruck wonderment. For generations, unsung tech pioneers have waded into the mysterious, subconscious rivers of the psyche, and conjured visions of Arcadian cityscapes or chilly galactic dystopias.

This capacity to evoke powerful sensations and images was seized upon by the radio, film, and TV industries, for whom electronic music offered a means of depicting a time and a setting – and prompting an emotional response – within a constrained budget. However, electronic music can also circumvent emotion altogether, tapping instead into the surreal, fragmentary world of dreams.

Visionary tech pioneers: shocking, thrilling, and perturbing

If electronica has long since lost any novelty value, it’s worth noting how the work carried out years ago by many of the most visionary tech pioneers still has the ability to shock, thrill and perturb. The example set by the early progenitors of musique concrète in the 40s cannot be underestimated: here was an ethos which arose from bold curiosity and a fascination with the potential of repurposed and recontextualized sound. In these instances, the “electronic” element had less to do with the use of electric signal generators and more to do with the principle of processing tape recordings.

Dating from 1944, “The Expression Of Zaar,” a reverb-heavy piece by the 23-year-old, Cairo-based Halim El-Dabh, is acknowledged as a crucial first step in the deployment of tape manipulation and post-production as compositional tools. (El-Dabh’s “Leiyla And The Poet,” from 1959, is another beguiling, Dadaist benchmark.) In Paris in 1948, Studio d’Essai founder Pierre Schaeffer debuted his startling “Cinq Études De Bruits” – reworked recordings of trains, boats, spinning tops, saucepans, and sinister, heavily treated piano – while 1951-52 saw Herbert Eimer and Robert Beyer constructing “Klang Im Unbegrenzten” (“Sound In Indefinite Space”) from the WDR Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne, set up with the stated aim of composing “directly onto magnetic tape.”

This “tone poem,” a stark wilderness of short echoes and whistling oscillators, relied upon pitch, duration, dynamics, and timbre rather than melody, harmony, and rhythm; but instead of adhering to the concrète methodology of refashioning recordings of acoustic sound sources, it was purpose-built from the ground up – a key artifact in establishing Germany’s elektronische musik.

Marrying opposite doctrines

It took another one of WDR’s tech pioneers, electronic studio operative Karlheinz Stockhausen, to successfully marry the two oppositional doctrines together, in 1956’s unsettling “Gesang Der Jünglinge,” in which the fluting, reconstructed and layered singing of a boy soprano meshes with filtered white noise and electronically generated pulses and sine-wave tones. (Stockhausen’s sonically ambitious “Kontakte,” assembled at WDR between 1958-60, represents another quantum leap in the elektronische musik realm.)

Europe in the 50s wasn’t exactly wanting for tech pioneers contributing to the development of music – nor suitable premises in which they could pursue their pet projects. Italy’s Studio Di Fonologia Musicale Di Radio Milano was set up in Milan in 1955 by Luciano Berio and Bruno Maderna, and subsequently played host to John Cage and Henri Pousseur: the former’s “Fontana Mix” (1958) and the latter’s “Scambi” (1957) were constructed there. Darmstadt’s Kranichstein Institute, meanwhile, contained the Studio Für Elektronische Komposition (opened in 1955), where Herman Heiss recorded “Elektronische Komposition 1” in 1956. Back in Paris, Iannis Xenakis, an engineering assistant to the architect Le Corbusier, applied architectural and mathematical criteria to the assemblage of such pieces as “Diamorphoses” (1958) under the aegis of Pierre Schaeffer’s Groupe Des Recherches Musicales.

Further afield, Tokyo’s NHK Studio opened an electronic music facility in 1955, thereby enabling the creation of formative electronic compositions by Toshiro Mayuzumi, and the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center was founded at Columbia University in 1958 (housing the ahead-of-the-game RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer), but it fell to Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe to get a similar initiative up and running in the UK that same year.

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop

Home to some of the most forward-thinking tech pioneers in music, The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was established in the corporation’s Maida Vale premises to satiate programmers seeking suitable soundtracks to complement the cutting-edge experimental drama which was increasingly infiltrating the Beeb’s radio and TV schedules. Oram had serious form in this regard, having joined the BBC in 1942 as a studio engineer, and using her formidable knowledge to concoct a groundbreaking electronic score for the corporation’s radio dramatization of Jean Giraudoux’s play Amphitryon 38 in 1957.

The workshop’s initial output included sound cues for Quatermass & The Pit and The Goon Show, but a visit to the Journées Internationales De Musique Expérimentale exhibition at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair strengthened Oram’s conviction that she needed to strike out on her own to fulfill her aspirations. She accordingly left the BBC in 1959 to set up her Oramics Studios For Electronic Composition in Tower Folly, a converted Kent oast house, devising a hugely imaginative machine which in essence enabled her to “draw sound” directly onto 35mm film. (The Oramics machine is now on permanent exhibition in London’s National Science Museum.)

Oram’s Electronic Sound Patterns EP, released on HMV Records in 1962, was intended as a whimsical accompaniment for “music and movement” interludes in 60s school halls, while her “Bird Of Parallax” stands as an illustrative example of the high-minded endeavors she continued to produce alongside regular commissions for her old employers at the BBC (plus adverts for the likes of soft drink Kia-Ora and Lego).

Oram’s departure from the Radiophonic Workshop cued the arrival of Maddalena Fagandini in 1959 and, semi-circuitously, Delia Derbyshire in 1960. Fagandini’s work for the corporation predominantly consisted of jingles and “interval signals,” short identifying phrases used in broadcasting. Beatles producer George Martin deployed one of Fagandini’s interval signals as the basis for “Time Beat,” released under the pseudonym of Ray Cathode in 1962. Derbyshire, meanwhile, generated much of the consistently innovative output that constituted the Workshop’s most celebrated era (and did so under a still-prevalent patriarchal rule, which made her achievements all the more remarkable).

Arguably best known for her radical interpretation of Ron Grainer’s Dr. Who theme music, Derbyshire exhibited an almost pathological need to push the envelope. Inventions For Radio (1964/65), four works created in collaboration with playwright/composer Barry Bermange, utilized a hallucinatory, disturbing sound design based upon repeated phrases and desolate, otherworldly backdrops. “The Dreams,” especially, haunts the unknowable recesses at the back of one’s psyche – “Everything is black, and I fall and fall and fall.” Over and above her BBC output, Derbyshire also set up Unit Delta Plus in 1966 (to promote and further the cause of electronic music) with fellow Radiophonic Workshop employee Brian Hodgson, and Peter Zinovieff, co-founder of the EMS company, which produced the archetypal VCS3 synthesizer in 1969.

Derbyshire and Hodgson subsequently launched the Kaleidophon studio with David Vorhaus, ostensibly to provide electronic music for theatre productions, exhibitions, and adverts. However, trading as White Noise, the trio of tech pioneers also recorded An Electrical Storm, released by Island in 1969 (and reissued in 2007): an exceptional undertaking that led to its own subgenre of creepily inscrutable electronic pop.

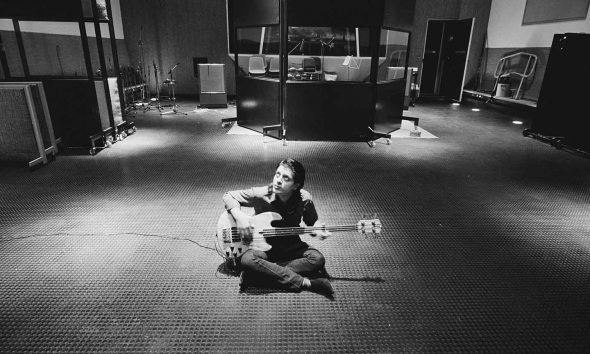

Synth pioneers

Mention of the VCS3 synth prompts a salute to composer Tristram Cary, who oversaw the device’s visual design. Some of Cary’s contributions to the electronic music canon can be found on Trunk Records’ It’s Time For Tristram Cary, while those of his EMS colleague Peter Zinovieff can be sampled on Space Age Recordings’ Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes compilation.

Over in the US, it was Robert Moog’s development of the Moog Synthesizer, demonstrated at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967, that popularized the apparatus as a credible instrument in its own right. Nascent Moogs were featured on recordings by, among others, The Monkees (“Daily Nightly,” “Star Collector”), The Byrds (“Space Odyssey”), Wendy Carlos (Switched-On Bach), and – lest we forget – The Beatles (Abbey Road).

Respect should also be accorded to mavericks such as the Canadian composer Bruce Haack, who built his own synths, modulators, and vocoder (which he named “Farad”) from a jumble of assorted electronic components. Haack’s The Electric Lucifer (1969) stands as a giddily individual totem of conceptual electronic acid-rock. US composer Pauline Oliveros, a founding member of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in the 60s, also designed her own signal processing system – as did Simeon Coxe III of Silver Apples, who constructed “The Simeon” from a bank of nine audio oscillators, several telegraph keys and an assortment of pedals.

Normalizing electronic music

By the 70s, an encouragingly enlightened mentality was slowly emerging, wherein a Club d’Essai alumnus such as Pierre Henry could feasibly cross-pollinate with a four-square rock band like Spooky Tooth (on the controversial Ceremony album). However, it fell to a couple of paradigmatic German outfits in particular to normalize the notion of electronic music – but not without an intermittently painful period of adjustment. By way of example, Tangerine Dream had two sets of keyboards destabilized when an outraged “fan” threw a bag of marmalade at them at a concert in the Theatre Parisien l’Ouest in February 1973, while the elegant and diffident Kraftwerk were bemused to encounter denim-clad hordes shouting “boogie” at them when they toured the US in 1975.

Such is the lot of the trailblazer. But we owe each and every one of the above-mentioned tech pioneers a debt for having the courage to open a portal into the delectably eerie unknown.

The 16CD and double-Bly-ray release, Tangerine Dream: The Virgin Recordings 1973-1979 is out now.