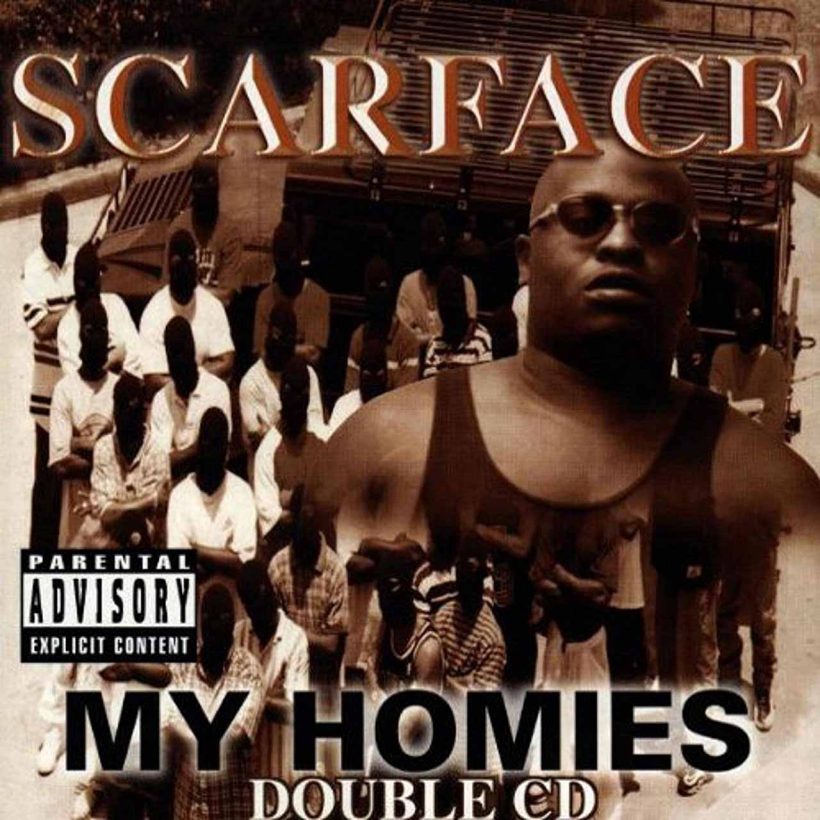

Scarface’s ‘My Homies’ Is A Vital Look at Houston’s Greatest MC

Released in March 1998, it’s a 137-minute double album that feels, somehow, small. Decades on, it’s still worth your time.

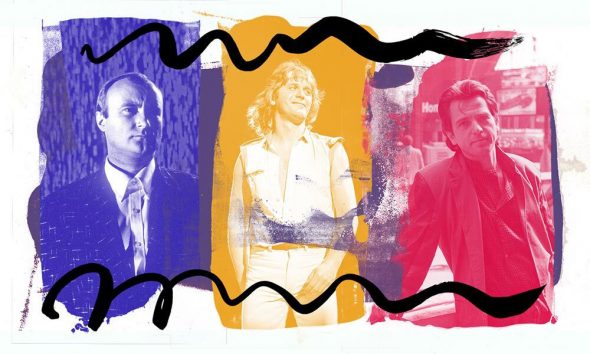

Three case studies: All Eyez On Me; Life After Death; Wu-Tang Forever. Those three double albums came out in quick succession, between February 1996 and June of the following year. Each was by a superstar rap act at the height of their power, and all three were acts of real-time mythmaking. 2Pac was fresh out of jail – as in literally; he was bailed of a maximum-security prison in upstate New York and flew immediately to California to write and record––and determined to exact revenge on, well, everybody. All Eyez On Me, the yield from a few weeks of marathon sessions, was breathless and brilliant. (When Pac was assassinated seven months later in Las Vegas, he was already mostly finished with a follow-up album.)

The Notorious B.I.G. was more calculated, but no less ambitious: his sophomore album, which he’d been writing and recording on both American coasts and in Trinidad, surveyed the entirety of mid-’90s rap and swallowed every style whole. Big was rapping on and about yachts; he was glowering at the Nasirs of the world who wanted the New York throne; he was recreating Delfonics songs with the band from the strip club next to the studio. And when the Wu-Tang clan reassembled in the studio after a string of massively successful solo debuts, their feelings about sustained supremacy were very clear: Wu-Tang Forever.

Listen to Scarface’s My Homies now.

What all those records had in common was a bone-deep desperation to be more than just another rap album, a dry-erasable scrawl on a release calendar. They were supposed to be definitive. What none of those records had was an entire song dedicated to Devin the Dude’s bodily functions.

Click to load video

Released in March 1998, Scarface’s My Homies is an anomaly of form, a 137-minute record that feels, somehow, small. Rather than a tome dedicated to status or biography, it’s a double album that was allowed to experiment, to lower stakes, to sprawl in any direction its creator saw fit. And when the creator is one of the greatest rappers to ever live, it becomes an absolutely arresting window into his creative life at the end of the 90s.

By the time My Homies came out, Scarface was already seen as a legend by some including, and perhaps especially, by those who reduced him to a regional cipher. Born Brad Jordan, Face grew up in Houston, a city he would eventually introduce to many rap fans from the coasts and the Midwest. At the outset of his career, and especially in his work with the Geto Boys – an already-existent group that he joined and quickly became the leader of – Face pioneered a new kind of gangsta rap, one that was less concerned with the linearity of murder plots of gang affiliations and more transfixed by the trauma that results from violence, be it splattered blood or psychological breakdown.

In 1991, the group scored a major hit with “Mind Playing Tricks On Me,” a masterpiece of a song that’s largely about post-traumatic stress. The same year, Face struck out on his own, with a debut album called Mr. Scarface is Back. It was his third album, 1994’s The Diary, which stands as his first classic: knotty, furious, and deeply felt, it rounds out his identity as a troubled, principled pillar of his city. It also announced him as a major artist, a rapper with the vision necessary to compete with his more famous and (at the time) critically adored peers in Los Angeles and New York. It debuted at No. 2 on Billboard; three years later, with the drug- and Smashing Pumpkins-inspired The Untouchable, he finally topped the charts.

Click to load video

In the run-up to My Homies, Scarface had been taking on more and more responsibility as a producer, under the tutelage of renowned Southern beatsmiths like Mike Dean and N.O. Joe. For his double album, Face took more of a lead behind the boards, appearing frequently as the primary or even solo producer for a track. Given his gradual takeover of the reigns, most of these beats are not a departure from previous Scarface records, skewing toward that same sneering funk he’d always defaulted too. (There are fascinating moments, however, where the sound runs right up to the border of the Beats By the Pound-helmed No Limit style that was exploding at the time.)

That new producing workload was mirrored by a decreased role on the mic. My Homies is nominally a Scarface album, but it lapses frequently into compilation territory, where the headliner is a role player – or absent completely – from a given song. While this strategy is not going to leave the marquee artist bronzed the way Big or Pac hoped they would be after their double albums, it has a variety of benefits. For one, Face’s pen never gets exhausted, and it keeps listeners’ ears from becoming fatigued of his voice. It also allowed him to show off an array of collaborators and proteges and, by implication, the diversity of sound in a South that was so often maligned by fans and critics. Some of those apprentices – chiefly Devin the Dude, whose solo debut came later in ‘98, also under Rap-A-Lot – have star-making cameos. (The aforementioned solo song, “Boo Boo’n,” is a nuanced story about crime and fidelity.)

One of the most magnetic guest spots came from the Ghetto Twiinz, a pair of sisters from New Orleans who bookend “Small Time,” on the album’s first disc. One of the things that’s readily apparent, aside from how simply acrobatic each woman’s delivery is, is what an influence 2Pac had become. Pac and Face had been collaborators, and “Smile,” from The Untouchable, became a hit after the assassination. Pac appears here, posthumously by way of a repurposed freestyle. That song, “Homies & Thuggs (Remix),” also features Master P, and therefore serves as a bizarre nexus for so much of what was happening in rap in 1998.

Click to load video

My Homies was girded by hits like “Fuck Faces,” where Devin, Tela, and a delightfully sleazy Too $hort reimagine romance. But what ensured the album would still stand proudly next to Face’s more concise works were verses like his last entry on the title track: “How dare you so-called black politicians/Knock me for the game that I explain to my listeners?/See, they wanna put me on remote control/So they can turn me on and off when they feel it, and try to take control/But I refuse to cooperate.”

Editor’s note: This article was first published in 2018.