‘2112’: Rush’s Landmark Album Explained

‘2112’ can be considered many things – a band manifesto, a conceptual landmark, maybe even the birth of prog metal – but above all, it was the band’s play for creative independence.

The year 1976 was a make-or-break time for Rush. It found them with ambition to spare, a growing cult audience, and a label that wasn’t sure what to do with them. It was time to pull together all of their disparate ideas into one major statement and they accomplish just that with their fourth studio album, 2112.

This was the crucial turning point for the band, the album that changed Rush from just another three-piece hard rock band, and set them on the path to greater glories. 2112 can be considered many lofty things – a band manifesto, a conceptual landmark, maybe even the birth of prog metal – but above all, it was the band’s play for creative independence. Let’s take a classic off the shelf and take another look at 2112 how it came to be.

Listen to 2112 on Spotify and Apple Music.

What led up to it?

A prime influence of 2112 was three years of constant touring, which made the band sharp enough to carry out its grandest ideas. Every Rush album had been a departure: The first was solid hard rock, minus the intellectual streak, but with a couple of numbers (“Working Man,” “In the Mood”) that would stay in the setlist for keeps. With Fly by Night, drummer Neil Peart came in and broadened their musical reach by adding his own lyrical ambitions, informed at the time by a love of sci-fi.

Ambition went through the roof on the third album, Caress of Steel, which was apparently inspired by seeing Yes on their Topographic Oceans tour and sported two epics, one of which covered Side Two. A fan favorite in retrospect, it was a career-threatening flop at the time. So it left Rush with two choices: streamline everything and get more straightforward, or do another epic and make sure they got it right. Characteristically, they chose to do both on separate album sides, but it was the epic that really got noticed.

Recorded at Toronto Sound Studios, 2112 proved as accessible as it was ambitious. The side-long Caress track “Fountain of Lamneth” was brilliant but dense, requiring a few listens to get your head around. But the “2112 Overture” charges right out of the gate with an Alex Lifeson fanfare riff. It remains Rush’s longest studio track, clocking in at 20:34, but each section stands out on its own.

What influenced 2112?

Musically Rush was still enamored with prog rock – the band had discovered Genesis and King Crimson as well as Yes – but didn’t put themselves in that category. In their minds, they were still a hard-rock band, with Jimi Hendrix and Cream roots. So it’s no wonder they were also big fans of The Who, since Tommy and Quadrophenia both proved that a hard rock band could write epic pieces. Lifeson told Rolling Stone in 2016 that the Who-like moments in 2112, especially the Pete Townshend-style strumming in the “Discovery” section, were no accident.

Also notable is the Tchaikovsky quote in the closing “Overture” solo that leads to a cannon blast (as it did in Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture”) which makes the opening lyrics, “And the meek shall inherit the earth,” all the more ironic. The album’s main lyrical influence proved more controversial. Drummer/lyricist Peart was a great admirer of the novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand (specifically her championing of the individual, not so much her right-leaning politics) and the lyric sheet carries a dedication to “the genius of Ayn Rand.”

What’s 2112 all about?

The title suite of Rush’s 2112 album is set in a totalitarian society where the evil priests of the Temples of Syrinx keep everyone in line. Stability is threatened when a young man finds a guitar, learns to make music on it, and believes the world needs to hear of his great discovery. After the priests of the temple destroy the guitar and send him packing, he envisions a world where music and creativity flourish. Knowing he’ll never see that world, he gives in to despair. The ending is left ambiguous: the singer may have committed suicide, but his struggle may have led to a toppling of the empire. After an instrumental finale with a vicious Lifeson solo, the listener is left with an ominous announcement, “We have assumed control.” A new beginning or a totalitarian clampdown? You decide.

The theme of the individual against totalitarianism was right out of the Ayn Rand playbook, but Rush personalized the story by giving it a young, idealistic hero – the same sort of misfit they’d salute in the later hit single “Subdivisions.”

As the band explained in the accompanying booklet to an anniversary reissue, there was personal relevance as well. The idea of being rebuffed for playing music was especially relevant to them since they were at risk of losing their record deal. Finally, the idea that a government would regulate artistic expression proved to be prophetic, since the days of stickered albums and the PMRC were only a few years away.

What is side two about?

The concept of Side Two of 2112 was…its lack of a concept. With its lighter mood and shorter songs (all under four minutes, if just barely) it almost sounds like a different band. Indeed, the first two songs were about the most down-to-earth topics Rush ever addressed: namely, smoking pot and watching TV. “A Passage to Bangkok” is something of a weed travelogue while “Twilight Zone” is about their love for that show.

Lifeson and Geddy Lee each take a rare turn writing lyrics, respectively on “Lessons” and “Tears,” both unusually gentle and reflective songs. With a Mellotron (played by Rush cover artist Hugh Syme) and a warm vocal, the latter sounds more like a Black Sabbath ballad (see ‘Solitude” or “Changes”) than anything else by Rush. More characteristically, the closing “Something for Nothing” hints at a near future when Rush would cram an epic’s worth of changes into a concise piece. Of these five songs, only “Bangkok” would get played live after the 70s, while “Lessons” and “Tears” were never done at all. As a whole, Side Two is a lost gem in the Rush catalog.

What was the reaction to 2112?

In their native Canada, the album cemented Rush’s icon status. They launched a triumphant arena tour that was captured on the next album, All the World’s A Stage, but in America they were now just a bigger cult band, still opening for the likes of KISS and Blue Oyster Cult. 2112 hit the Billboard Top 200 albums chart and saved their career, but the days of platinum albums and US arena sellouts were yet to come. Even in its looser days, American FM radio wasn’t sure what to do with Rush, so it usually did nothing. Not until the next studio album, A Farewell to Kings, was there a track, “Closer to the Heart,” that it could get behind.

What’s its significance?

For many fans, 2112 is the one where they got on board. And while future albums, especially Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures, sold better and got more airplay, 2112 was the one that made three decades of further experiments possible. Rush never played a show without including some of it, usually the “Overture/Temples of Syrinx” section during the show-closing medley. Fans also rejoiced when the entire suite was played live in the 1996 Test for Echo tour – the only time the band played it through without omitting one of the quieter sections.

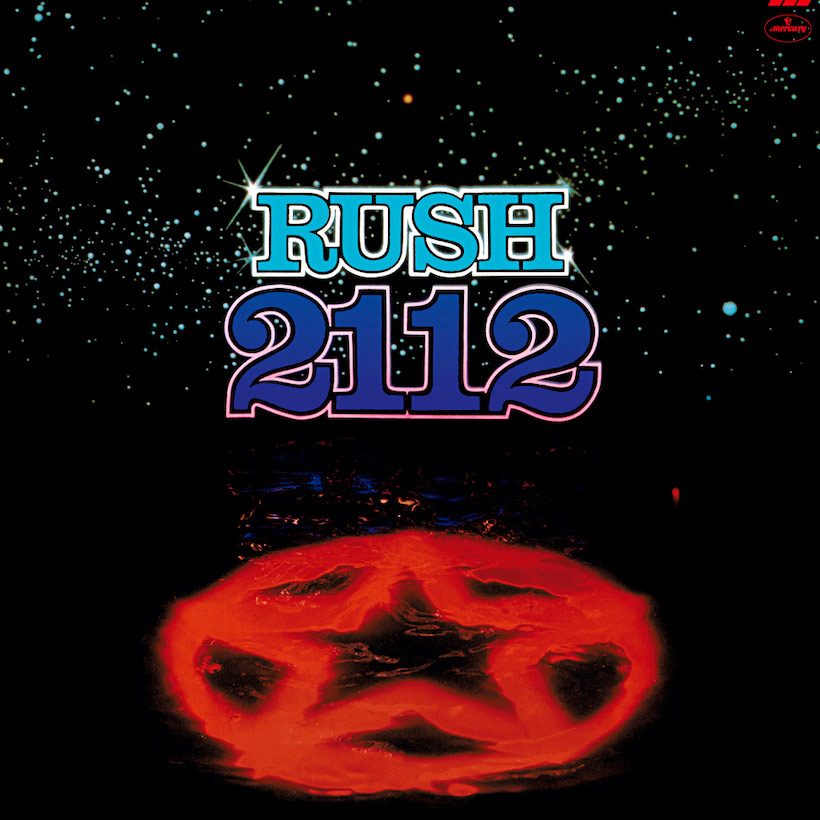

Famous fans also took the album to heart. The 2112 anniversary box set boasted cover versions by modern heroes of prog (Steven Wilson), post-grunge (Alice in Chains), and stadium rock (Foo Fighters) that showed just how far their influence went. Just as notably, Syme’s cover art established a key piece of Rush iconography: the “Starman” logo. Featuring a naked figure staring down the symbol of power, it represented the individual taking control. It’s their main Ayn Rand takeaway and a key part of what Rush was all about.

What direction did Rush’s music go in after 2112?

Musically, the band was just getting started. The next two studio albums, A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres, were even more ambitious, with Geddy Lee now adding keyboards. The next big piece, “Cygnus XI,” was so epic that it spilled over onto both albums. That’s when Rush decided that long concept pieces were a dead end, and claimed the right to absorb whatever new music struck their interest. The next three decades would be a wild ride, but the Red Barchetta was revved up and ready to go.

Geoff

April 3, 2021 at 8:02 am

3rd Paragraph. What is 2112 About.

50th Anniversary edition? When did that come out? 2026??? Don’t you mean the 40th Anniversary

Todd Burns

April 9, 2021 at 8:27 pm

Thanks for the catch! We’ve updated the piece now.

Pablo

April 3, 2021 at 3:27 pm

I think you mean 2112’s 45th anniversary, right? Also, I would argue that ‘Exit…Stage Left’ deserves a bigger article, as its 40th anniversary just passed by (most of the concert recordings were on March 27th, 1981, Montreal). Now THAT was a performance for the ages. Nothing pre-recorded, no tracks, no playback. Just three twenty-something geniuses at their best, literally “in the zone” (the 1-2-3 punch of Broon’s Bane-The Trees-Xanadu is simply sublime). IMHO, the best live performance of any band, of any genre, anytime, anywhere.

Gonzalo Donoso

April 3, 2021 at 7:05 pm

Exactamente, sublime,virtuosa, potente y con solo 3 músicos excepcionales que a sus 28 años,ya eran iconos del rock en toda su dimensión.

pud666

February 10, 2024 at 7:26 am

Overture does not end with a canon blast. It is a thunder sheet. I doubt they would use that as a canon blast. What do I now?