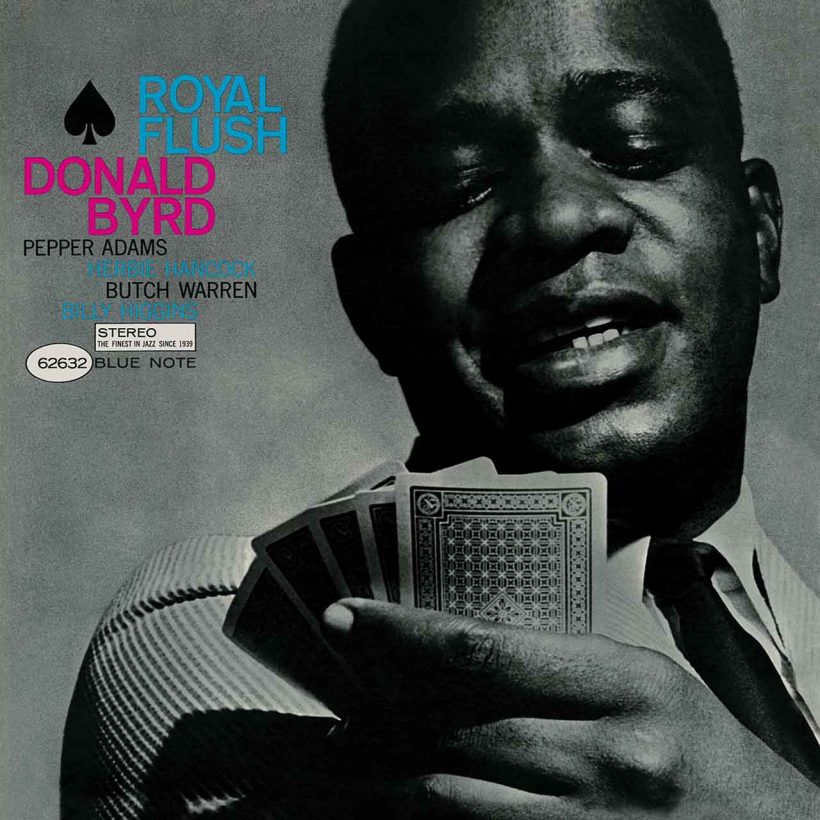

‘Royal Flush’: The Winning Hand That Took Donald Byrd In A New Direction

With ‘Royal Flush,’ Donald Byrd held a few aces up his sleeve, pushing the boundaries of hard bop while also introducing Herbie Hancock to the world.

On Thursday, September 21, 1961, Detroit trumpeter Donald Byrd took a quintet into Rudy Van Gelder’s famed New Jersey recording studio to lay down the tracks for what became Royal Flush, his eighth album for Blue Note Records. Though still only three months shy of his 29th birthday, Byrd could almost be considered a veteran at this point, such was his experience both on stage and in the recording studio. Indeed, his CV was mightily impressive, including a stint as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, alongside work as a sideman on albums by John Coltrane, Hank Mobley, Horace Silver, Jackie McLean, Red Garland, Lou Donaldson, and numerous others.

Despite his relative musical maturity, Byrd’s quintet revealed that he was willing to take a chance on youth and inexperience. In his band was a largely untested 21-year-old pianist called Herbie Hancock, whom the trumpeter had discovered in Chicago. He was struck by Hancock’s unique style – “He sounds almost like a combination of Bill Evans, Ahmad Jamal, and Hank Jones,” Byrd remarked to writer Leonard Feather in Royal Flush’s original liner notes – and also recruited a young rhythm section that had caught his ear, bassist Butch Warren and drummer Billy Higgins, both of whom had cut their teeth with free jazz maven Ornette Coleman. All three young men – Hancock, Warren, and Higgins – would quickly become stalwarts of Blue Note sessions in the next few years. But while Byrd was giving youth a chance, he also continued his long association with a fellow veteran, Michigan musician Pepper Adams, whose husky baritone saxophone imbued the trumpeter’s band with earthy sonorities.

“Hush” is the first of four original Byrd tunes on Royal Flush, and in terms of structure, as well as the synthesis of blues and gospel inflections, it is an archetypal piece of early 60s hard bop. Higgins and Warren establish a swinging groove and, after the “head” theme, each member of the band proceeds to solo, with Byrd at the front of the queue.

Byrd displays his prowess as a balladeer on the forlorn “I’m A Fool To Want You,” a song co-written by Frank Sinatra, who recorded it first in 1951 and then waxed a definitive version six years later. Behind Byrd’s luminous trumpet lines – he’s the only soloist on the cut – Hancock plays masterful delicate chords while the rhythm section grooves along slowly and softly.

The Byrd-written “Jorgie’s,” named after a St Louis nightclub, begins as a more progressive slice of jazz with a spacey intro before morphing into a medium-paced piece of swinging hard bop. The intriguing “Shangri-La,” meanwhile, is another Byrd composition that offers something different, especially in relation to Billy Higgins’ drums, which, instead of playing a fixed, regular, swing-type pattern throughout, have more of a freer, individual role. This gives the track a jagged, stop-start feel.

Herbie Hancock’s languid piano begins the loping “6 M’s,” played in 6/4 time, and on which Byrd and Adams enunciate the theme in an authentically classic hard bop fashion. It offers an opportunity for all the players to show their affinity for blues music, with Hancock impressing via a funkified piano solo.

It’s Herbie Hancock who shows his hand on Royal Flush’s final track, “Requiem.” The first of the pianist’s compositions to be recorded, despite its title the music is far from solemn or morose. After an intro defined by the call-and-response cadences of gospel music, it evolves into a swinging groove with deft solos from Byrd, Adams, Hancock, and even Warren, who gives us a brief taste of bowed double bass.

Royal Flush remains a significant album in Donald Byrd’s canon. While it waved goodbye to a five-year association with Pepper Adams – it would be his and Byrd’s final collaboration together – it also introduced the world to his protégé Herbert Jeffrey Hancock, who, shortly afterward, would go on to make his mark as both a solo artist and as a member of the groundbreaking Miles Davis Quintet.

Though Hancock left Blue Note in 1969 to start new adventures elsewhere, Byrd stayed with the label until 1976, by which time he was in the vanguard of the fusion and jazz-funk movements. Even so, Royal Flush remains a go-to album from the trumpeter’s golden hard bop period, even though it finds him stretching the boundaries of the genre. But that wouldn’t have been possible without the presence of Herbie Hancock, Butch Warren, and Billy Higgins. They were the aces up Byrd’s sleeve, and their youth opened up new vistas of sonic expression, helping to take the trumpeter – and jazz – in an exciting new direction.