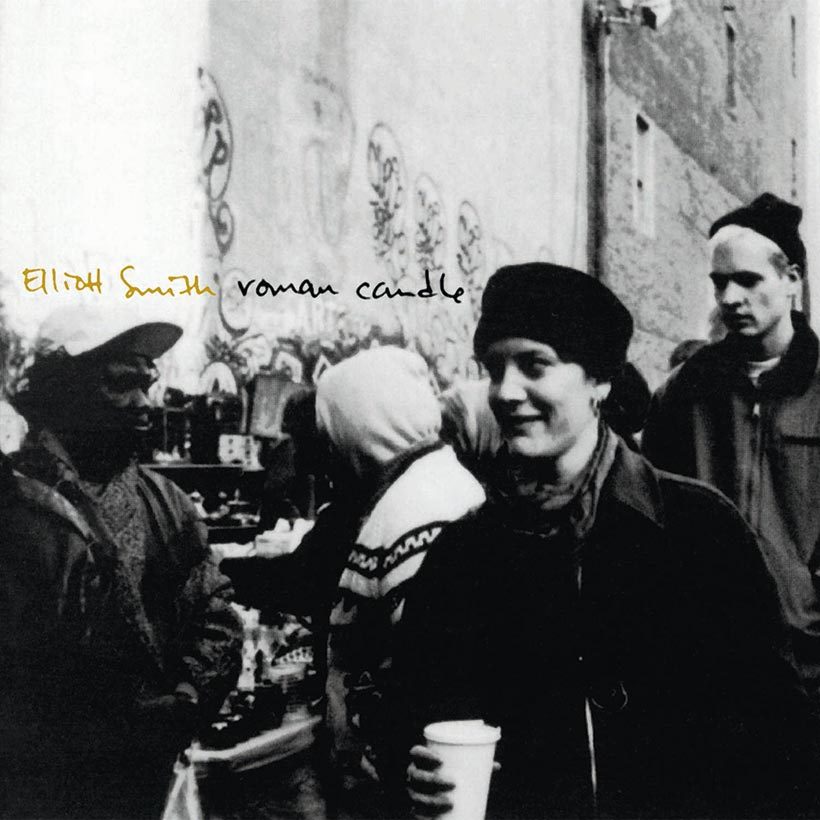

How ‘Roman Candle’ Lit The Spark For Elliott Smith

Intimate and spontaneous, ‘Roman Candle’ laid bare the threads of Elliott Smith’s songwriting, acting as a prelude to his career.

Back in 1994, nobody, least of all Elliott Smith himself, would have taken a bet on the singer-songwriter making an appearance at any awards ceremony, let alone the Oscars. Yet, just four years after the release of his debut album, Roman Candle, there he was, in a slightly crumpled white suit, barely able to look up as he performed “Miss Misery,” his contribution to the Good Will Hunting soundtrack that had been nominated for the Best Original Song award.

Watching the footage now, it’s a remarkable moment, but more of an odd footnote rather than the career highlight it would represent for most artists. That’s because Smith would go on to become one of the most cherished songwriters of his generation, releasing a string of albums of ever-increasing ambition, melodic dexterity, and bittersweet beauty.

It all started with Roman Candle though, a debut collection that poses the question, When is an album not an album?

Do you love 90s music? Buy the best 90s music on vinyl here or stream it on this playlist.

Like numerous early rock’n’roll sets, or albums the likes of Third/Sister Lovers, by Smith’s beloved Big Star, the songwriter never intended Roman Candle to be heard as a standalone record. He’d been stockpiling material since he was a teenager, not all of it especially suited to the more raucous grunge-informed rock of Heatmiser, the Portland post-hardcore group he sang and played guitar with. These songs were wispy, hushed confidences that would require more careful treatment than his band could offer. When JJ Gonson, Heatmiser’s then-manager and Smith’s girlfriend, became aware of his extra-curricular writing, she insisted he record demos on the most basic of equipment – toy guitar and all – in her basement, with a view to passing the songs on to Cavity Search Records’ co-founder Denny Swofford.

The tape soon did the rounds in local circles, creating a buzz as its bare-bones acoustic folk/grunge/pop hybrid snuck its way into the affections of those in the know. Whether Smith was completely aware of this is a moot point, but Swofford persuaded him to allow him to release the tracks as they were. The two of them shook on it (no contract, making the release seem even more low-key), and, gradually, as if by osmosis, Smith’s songs began to sneak out into the wider world, following the release of Roman Candle, on July 14, 1994.

Listening now, the album seems to act as a prelude to Smith’s career. Across its sometimes half-formed, spontaneous, shy-sounding nine recordings, the threads that Smith would later weave together are laid bare – his rare gift of finding unexpected but satisfying chord progressions and decorating them with dextrous melodies; kitchen-sink stories of people living chaotic lives; sweetly-sung lyrics dealing with deep disillusionment and dejection. Future albums such as XO and Figure 8 would show how ambitious he’d become in terms of arrangements, but Roman Candle shows that the songs were in place long before.

It starts with the title track. Rather than strumming the guitar, Smith brushes continuously against the strings as if worried that he’d wake somebody. The listener is almost forced to bend towards him, keening to hear, creating a feeling of real intimacy – the sort that fans cherish, that makes them feel closer to the artist they love. There’s a point in the middle eight when the song feels as if it might unravel completely, calling to mind Smith’s final recordings, posthumously released as From A Basement On The Hill. Elsewhere, the pretty melody and detached vocals of “Condor Avenue” offer the clearest signpost as to what Smith was capable of, while ‘Last Call’ is the first of the strung-out, wracked epics that would pepper later albums.

In terms of Smith’s revered body of work, Roman Candle lit the touchpaper for all that would follow.