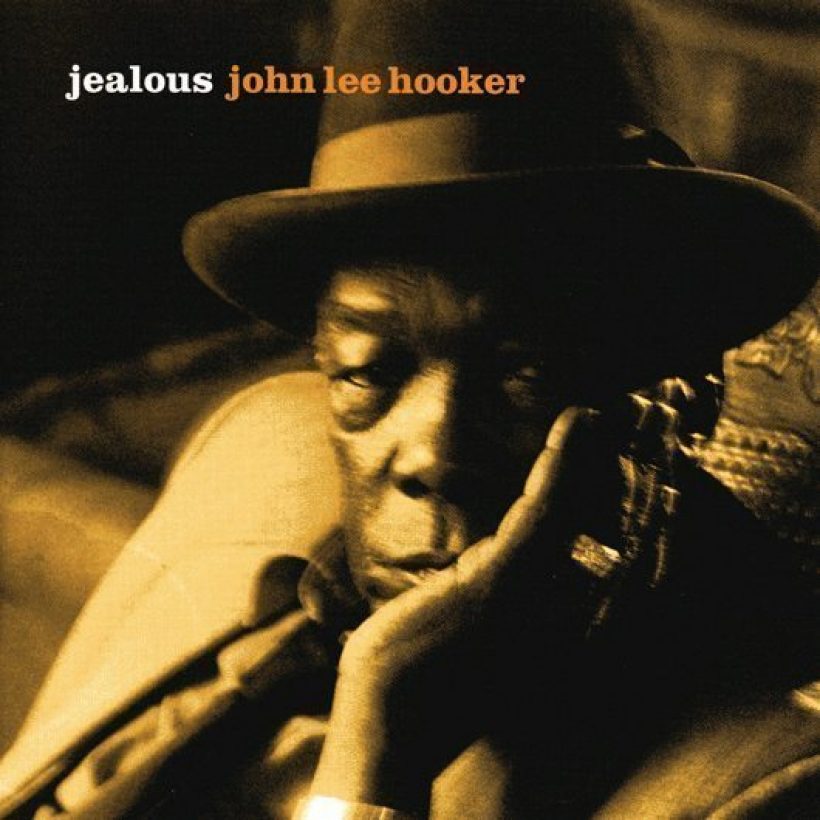

reDiscover John Lee Hooker’s ‘Jealous’

What was the original bluesman’s place in the mid-1980s? Many of John Lee Hooker’s contemporaries had checked out, leaving him to find his own way. He could have earned a decent living as a retro act, playing the festivals and winning ovations simply for staying alive. Instead he chose to be a contemporary artist, taking his music to new audiences and working with musicians who were associated with the rock arena rather than its daddy, the blues.

Before you decide to look elsewhere (there have been many musical crimes committed with the aim of updating the blues), on Jealous the updates have been made with taste, and an evident empathy for Hooker’s amazing abilities. The band may sound huge at times, but the singer is the focus and sounds fully in control, as he did in his 50s and 60s prime. There’s a reason for this: he produced the album. The horn arrangements are tight and to the point, and the guitars rock, but not to the detriment of the star of the show. What you want from a John Lee Hooker album is atmosphere – something the singer was capable of creating all on his own. The risk here, where he was fronting a fairly large band on some tracks, was drowning it. That didn’t happen, and each track sets up a mood as effectively as if he was performing solo.

As the original album sleeve boasted, this was Hooker’s first studio album since 1978 – an eight-year hiatus. Perhaps he’d been saving it all up, because he sounds like he’s got plenty to get off his chest. The title track burns along, the rhythm a sped-up shuffle, the horns swinging tighter than James Brown’s and every bit as funky, but the attitude is pure Hooker boogie. ‛Ninety Days’ hits nearly as hard, grinding close on seven minutes of grits before Hooker allows himself a breather with the slow wailer ‛Early One Morning’. He returns to his early-60s gem ‛When My First Wife Left Me’, summoning up the some of the regret of the original and replacing what was missing with the perspective of an old man – Hooker was 69 when he cut this album. Maybe he was thinking of the same ex when he sang ‛We’ll Meet Again’, another ballad, in which he is supported by organ straight out of the church from the song’s co-writer Deacon Jones.

If that all sounds like simply a blues album, rather than a rockish one, your assessment is correct, except that the guitars (from Bruce Kaplan, Jamie Bowers and Mike Osborn) are a shade more obtrusive than they would usually be in Chicago’s heyday and given a tad more distortion, and the sound is precise, spacious and contemporary. (Curiously, the best known rocker on the project, Carlos Santana, is restricted to writing the sleeve notes, though that would be rectified on future records.) But Hooker remains himself, and the richness of his voice comes through as well as ever. It’s his rivals – those that were left – that should have been Jealous. If only all updates of the blues were as tasteful and genuine as this one.