‘Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)’: How Brian Eno Plotted Art Rock’s Future

With his second solo album, ‘Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy),’ Brian Eno introduced his Oblique Strategies cards, with seductively subversive results.

A mere 10 months after his solo debut, Here Come The Warm Jets, Brian Eno consolidated his standing as one of rock’s least orthodox provocateurs with the release of the seductively subversive album number two, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy). Issued by Island Records in November 1974, Taking Tiger Mountain derived its title from a set of postcard photos depicting a Peking opera, one of the eight “model plays” permitted during the Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966-76. Indeed, references to China recur in the album’s lyrics, hence a widespread assumption that the album is a concept piece – though this remains tricky to substantiate.

Listen to Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) on Apple Music and Spotify.

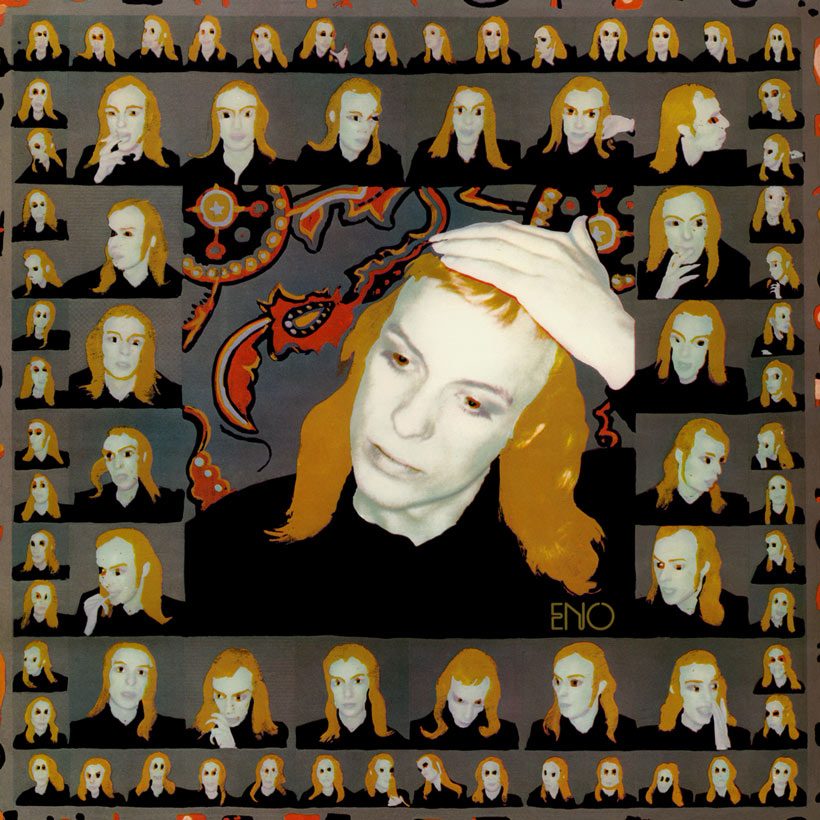

Central to the new record’s creation was the principle of “Oblique Strategies”, a set of instruction cards devised by Eno and his artist friend Peter Schmidt (who also designed Taking Tiger Mountain’s sleeve). The cards, which Eno would regularly consult in succeeding years, were intended to derail recording and production techniques, overturn habits and/or inspire new avenues of thought in musicians and producer/engineers alike.

Some instructions were boldly challenging – “Ask people to work against their better judgment,” “Change instrument roles,” “Give way to your worst impulse” – while others teasingly contradicted those found elsewhere in the deck (“Don’t be frightened of clichés,” “Don’t break the silence,” “Fill every beat with something”). Several were decidedly holistic – “Get your neck massaged,” “Tidy up,” “Breathe more deeply.”

The result of this fresh methodology was an album which, with hindsight, represents a bridge between the voluble, impish, glammy decadence of Here Come The Warm Jets and the more pensive works which were to follow. Eno’s former Roxy Music bandmate, guitarist Phil Manzanera, and erstwhile Soft Machine vocalist/drummer Robert Wyatt were principal collaborators on an album that drew upon the input of a consistent studio ensemble, but which also found room for several memorable guest cameos. These included The Portsmouth Sinfonia’s queasy strings in the sinister lullaby “Put A Straw Under Baby,” Phil Collins’ measured drumming on “Mother Whale Eyeless” and a staccato sax part on “The Fat Lady Of Limbourg,” tackled by another of Eno’s former Roxy bandmates, Andy Mackay.

For all that Taking Tiger Mountain exalts in the deployment of apparently random factors, Eno’s contention that his lyrics were more about sound than sense is slightly disingenuous. The album’s songs are vividly allusive, but narrative threads quietly unspool in the background. “The Great Pretender,” blank and chilly, concerns the rape-by-machine of an ironically robotic and subservient housewife (“Joking aside, the mechanical bride has fallen prey to the great pretender”). The cautious, deliberate “The Fat Lady Of Limbourg,” meanwhile, draws its inspiration from a Belgian asylum where there are more inmates than there are residents in the surrounding town, and “Burning Airlines Give You So Much More” reimagines the crash of Turkish Airlines Flight 981 in March 1974 as a languid Chinese and Japanese reverie (“How does she intend to live when she’s in far Cathay? I somehow can’t imagine her just planting rice all day”).

If “China My China,” with its rhythmic bed of typewriters, represents an ambivalent paean, “Mother Whale Eyeless” is sufficiently immediate that it might have been considered for a single, had it not been for some characteristically abstruse lyrics (“There’s a pie shop in the sky”). However, this is Taking Tiger Mountain’s appeal in a nutshell: for all its freely indulged eccentricities, Eno’s innate and knowing ear for pop shapes, unlikely but nagging hooks, and natural structures maintains an impeccable balance.