How Prog and Fusion Became Kissing Cousins in the 70s

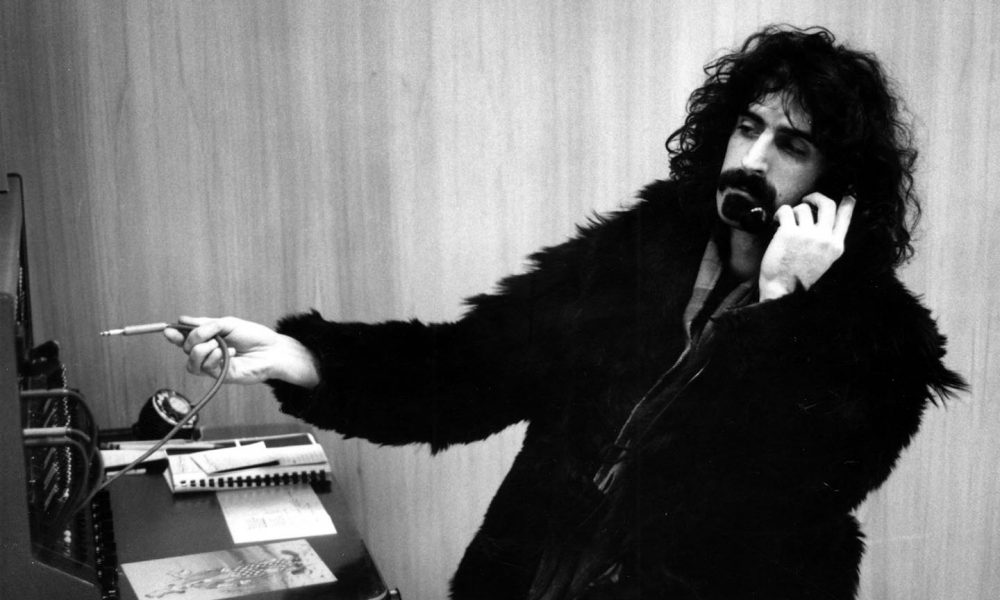

When progressive rock and jazz fusion first emerged, they were worlds apart. Acts like Frank Zappa, Brand X, and more changed all that.

When progressive rock and jazz fusion first emerged, they were worlds apart. Just compare Miles Davis’s jazz-rock milestone Bitches Brew and Gentle Giant’s classically influenced, uber-proggy debut. Both blew minds in 1970 with their expert musicianship and bold new visions, but they also underlined the distance between prog’s ornate, intricately arranged meisterwerks and fusion’s free-wheeling, improv-oriented expeditions.

Don’t peg all progressive bands as stately baroque-rockers though. A subset of 70s prog musicians more besotted with Miles than Mozart bypassed highly arranged symphonic rock and channeled their heavy-duty chops in jazzier directions. The crossover encompassed fusion bands born from the prog scene (Gilgamesh, Hatfield & The North, Brand X, Colosseum II), progressive rock bands with high-profile fusion offshoots (U.K.), and artists who worked both sides of the fence (Gong, Frank Zappa).

Listen to the best of Prog Rock on Spotify.

Probably the biggest single nexus of prog/fusion crossover was the Canterbury scene. In the late 60s, Soft Machine was the spiritual center for the loose agglomeration of bands that took jazz’s heady harmonic innovations and improvisational elan and rendered them with rock tools. Some key Canterbury bands, like Caravan and the early incarnations of Soft Machine, leaned closer to rock. But outfits like Hatfield and the North (which included former Caravan bassist/singer Richard Sinclair) found their feet in the fusion realm.

On Hatfield’s self-titled 1974 debut album, the Chick Corea-informed electric piano impressionism of Dave Stewart (not to be confused with the Eurythmics co-founder) and the splashy swing of drummer Pip Pyle definitively tilt the balance towards jazz. As often as not, when voices appear they’re basically used as wordless instruments, and when guitarist Phil Miller abandons his post-bop glide for a fuzzier sound, it’s more John McLaughlin than Jimi Hendrix.

Hatfield were close cousins to Gilgamesh. Stewart co-produced the latter’s 1975 debut LP, sometimes sat in with the band, and later formed the similarly inclined National Health with Gilgamesh keyboardist Alan Gowen. Like Hatfield and the North, Gilgamesh only lasted for two albums, but unlike Hatfield, they operated without a trace of rock sensibility, abandoning vocals completely, as Gowen’s dazzling multi-keyboard mastery brought the band to even deeper levels of jazzy harmonic complexity than Stewart’s band.

Gong was founded in France, but their various lineups had numerous ties to Canterbury. Initially led by Soft Machine co-founder Daevid Allen, they started out as psychedelic rock pranksters, but with the arrival of Pip Pyle and saxophonist Didier Malherbe, their high-concept space rock started taking a jazzier turn. And after Allen split in 1975, they evolved into a full-on fusion band. On all-instrumental records like Gazeuse! and Expresso II, drummer Pierre Moerlen took the reins, instituting a somewhat Zappa-ish approach that leaned heavily on interlocking mallet percussion patterns. (Moerlen, his brother Benoit, and Mirielle Bauer constituted Gong’s mighty percussive triumvirate).

Speaking of drummer-fronted bands, Colosseum played a mix of proto-prog, jazz, and blues in the late 60s, with hotshot Jon Hiseman leading the charge from behind the kit. But after the initial lineup split – with keyboardist Dave Greenslade starting the prog band that bore his surname and taking bassist Tony Reeves with him – Colosseum II eventually arose as a fire-breathing fusion group.

Hiseman was still at the fore, surrounded by an entirely new crew including guitar hero Gary Moore, keyboardist Don Airey, and onetime Gilgamesh bassist Neil Murray. After their first album they sacked singer Mike Starrs and focused on their wheelhouse: a jazz-rock shred-a-rama comparable to Al Di Meola-era Return to Forever, with licks worthy of UN monitoring as weapons of mass destruction.

You can’t get much further from jazz than 70s Genesis. But just as Phil Collins was making his first foray from behind the drums to the frontman spot after Peter Gabriel’s departure, he seemingly decided he needed even more of a challenge. So, he let his inner jazzer out and became a charter member of British fusion giants Brand X. Early lineups even briefly included Yes’s Bill Bruford and Camel’s Andy Ward on additional percussion.

On 1976’s Unorthodox Behaviour and follow-up Morrocan Roll, Brand X was as funky and swinging as any American fusion band. Fleet-footed Collins unleashed all the jazzy moves Genesis had no call for, and the seemingly four-handed bassist Percy Jones proved himself to be the UK’s answer to Stanley Clarke.

The aforementioned Bruford had even more jazz in his heart than Collins. And when he’d (at least temporarily) had his fill of making prog rock history with Yes and King Crimson, he buzzed off to lead a fusion band of his own: Bruford. He brought along superhuman guitarist Allan Holdsworth from his previous band, prog supergroup U.K. The ubiquitous Dave Stewart joined on keys, and American bass phenom Jeff Berlin completed the original lineup.

Feels Good to Me and One of a Kind are late 70s jazz-rock classics, with Holdsworth approaching his guitar like a saxophone, Stewart delivering next-level synth splashes, and Berlin displaying his poetic, Jaco Pastorius-level bass gifts. After the band ended, Holdsworth built his legend as a solo fusion guitar god, and Bruford forsook electricity in his post-bop band Earthworks.

When Bruford vacated the drum stool in U.K., he was replaced by American octopus Terry Bozzio, whose jazzy, stateside CV could have made his predecessor sigh with envy. Bozzio worked with jazz greats like Woody Shaw and Eddie Henderson as well as fusion legends The Brecker Brothers, but his most high-profile gig was his stint with Frank Zappa’s band (which at one point also included another member of U.K., keyboardist/violinist Eddie Jobson).

All throughout his career, Zappa flipped between formats as it suited his muse, jumping between prog, blues, modern classical, doo wop, and whatever else was whetting his mercurial whistle at the moment. But the merger of jazz and rock was a particularly sweet spot for the mustachioed maestro, and he visited it multiple times over the course of his long, eclectic journey.

Besides being one of the most lyrical and nimble electric guitar stylists of his generation, Zappa (much like Miles Davis) constantly surrounded himself with virtuosic players. Some of the biggest fusion stars of the 70s logged stints in Zappa’s band, including George Duke and Jean-Luc Ponty. And on albums like Waka/Jawaka, Hot Rats, The Grand Wazoo, and Sleep Dirt, to name just a few, Frank and company came to the table with enough fiery solos and ensemble bravura to make some of the most searing jazz-rock statements ever.

By the time the 80s rolled around, the rarefied cultural climate that made such complex, challenging sounds sustainable on a mainstream level had changed. Top-tier prog and fusion bands like Gentle Giant, ELP, Return to Forever, and Mahavishnu Orchestra had called it quits, and others altered their approach in order to survive.

But in that golden window between the ascension of the counterculture and the tabula rasa effect engendered by the punk revolution, lofty musical ambitions were not only tolerated but encouraged. And when two of the era’s most ambitious subgenres crossed their streams, it made for some of 70s music’s most luminous lightning strikes – brainy and bad-ass in equal amounts.

Looking for more? Check out our list of the best 50 prog rock albums of all-time.

cogakih

August 22, 2023 at 6:25 am

HY

Rik_K

September 25, 2023 at 3:33 am

Seems like progressive rock has made something of a comeback in recent years, and been broadly re-assessed without all the ignorant prejudices that used to be stacked against it. Does the same hold true for Jazz-Rock Fusion? I collect books on music, and while I have many books about Prog, I have only found one about Fusion, and that one is decades old now.