The Far Side of Peggy Lee: Her Most Exploratory Songs And Albums

In decades of recording, Peggy Lee dipped into many styles. But a trio of releases represents some of her most adventurous explorations.

In 50-plus years of recording, Peggy Lee dipped into jazz, pop, Afro-Cuban, stage and movie music, and much more. But a trio of releases from three different decades represents some of her most adventurous explorations. Lee always followed her muse wherever it led. Sometimes her most outside-the-box efforts became huge successes. Sometimes they ended up unsung masterpieces. Let’s dig into the backstories of the Peggy Lee catalog’s artful outliers.

Listen to Peggy Lee’s new archival release, From the Vaults, Vol. 2 now.

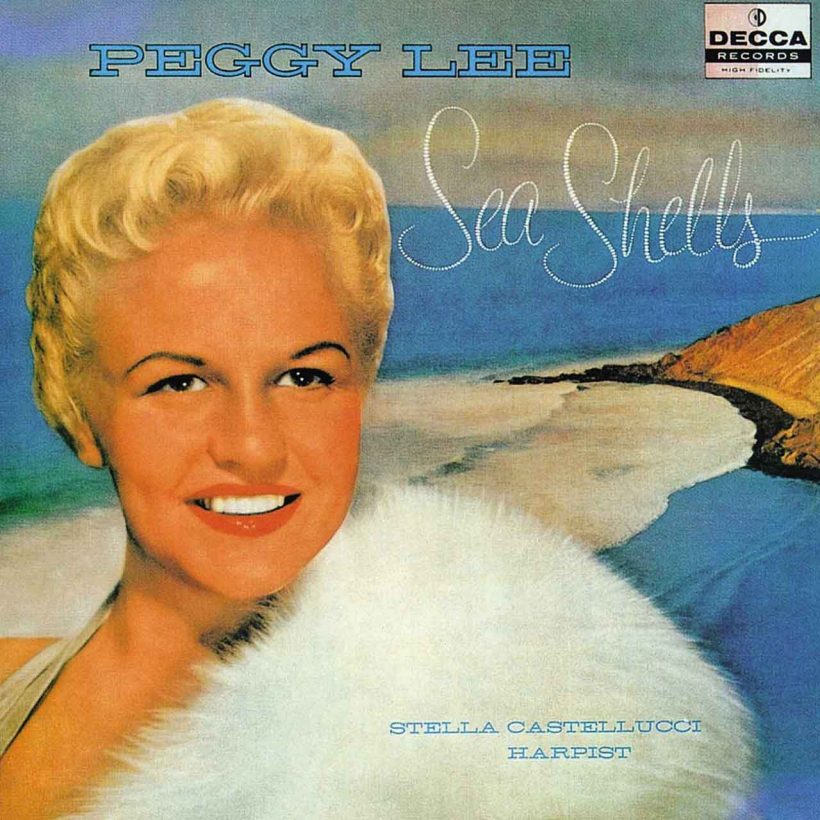

SEA SHELLS

By the time Sea Shells came out, Peggy Lee was a bona fide pop star who’d been cranking out hits for 17 years. The 1958 album still sounds radical today, so at the time it must have seemed positively otherworldly.

Sea Shells features minimalist settings of Chinese poems and an international array of folk songs, with only harp and occasional harpsichord for instrumental backing. The album was Lee through and through. Unusually for the time, she even wrote the liner notes herself. Inspiration arrived when her manager gave her the 1932 book Music of Many Lands and Peoples, which started the singer thinking about drawing from multiple musical traditions.

Lee took translations of pieces by eighth century poets like Li Po and Tu Fu from the 1942 book Chinese Love Poems. Lee’s life was known for its emotional turbulence, and she found a spiritual succor in the poems. She chose harp and harpsichord for their old-world air, calling on jazz pianist Gene DiNovi for the latter, even though he later admitted, “I’d never played harpsichord in my life.” Nevertheless, he drummed up some dreamy, artful accompaniment, as did harpist Stella Castellucci, who remembered Lee musing, “These songs are such small, delicate things; why don’t we call them sea shells?”

Fearful of Sea Shells’ unconventionality, Decca sat on the 1956 sessions until 1958, the year in which Lee’s smash “Fever” made even an offbeat album seem potentially salable. It wasn’t. Despite the record’s innovative beauty, the mainstream was wary. A cautious Record Mirror review called it “somewhat weird,” warning that “only Peggy purists will get full value.” Today, that opinion seems silly. You don’t have to be a Peggy Lee purist to be struck by the music’s simultaneously haunting and soothing spell, especially on the tracks where Lee’s placid spoken-word delivery comes to the fore.

Listen to Peggy Lee’s Sea Shells now.

IS THAT ALL THERE IS?

Over a decade later, a pair of rock ‘n’ roll legends became the unlikely architects of Peggy Lee’s biggest attention-getter and most left field recording ever.

Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller were most famous as the writers behind “Jailhouse Rock,” “Hound Dog,” “Yakety Yak,” and hordes of other rock ‘n’ roll classics. In the early 1960s, they worked together with Lee on the single “I’m a Woman” and a subsequent album of the same name (both received Grammy nominations). But that was only phase one of the trio’s shared destiny.

Later in the decade, the world was changing, and so were Leiber and Stoller’s ambitions. According to The Word, Leiber would later explain that they “were getting older. We weren’t writing for kids anymore. We were looking for another, more mature audience.” In the team’s autobiography, Hound Dog, Stoller details what came next. “Jerry and I had been talking about stretching out as writers….Jerry’s vignettes ached with the bittersweet irony of German cabaret. I wrote music that I hoped caught the spirit of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht.”

The result was “Is That All There Is?” based on the 1896 story “Disillusionment” by Thomas Mann, in which a man reminisces about traumatic events from his life, coming away from each one with a kind of existential ennui. When Lee heard the songwriters’ demo, she said, “I will kill you if you give this song to anyone but me. This is my song. This is the story of my life.” She speaks the verses in an appropriately detached deadpan, singing the choruses like a postmodern Lotte Lenya, and landing on an iconic tagline: “Let’s break out the booze and have a ball if that’s all there is.”

Working with the trio was a young Randy Newman, who provided an arch, eccentric arrangement. Lee was a fan of his first album and her enthusiasm inspired Leiber and Stoller to hire him. Even in the late ‘60s, when psychedelia was opening minds and ears wider than ever before, there was nothing else like “Is That All There Is?” At first, Capitol didn’t even want to release it. But the song became a phenomenon, bringing Lee – who hadn’t hit the Top 40 since “Fever” more than a decade earlier – back into the limelight, even earning the singer her first GRAMMY® award.

Listen to Peggy Lee’s “Is That All There Is?” now.

MIRRORS

Leiber and Stoller always wanted to pen an entire Peggy Lee album, but they had to wait several years until the stars aligned. They wrote and produced Lee’s 1975 LP Mirrors, finally achieving a full-length embrace of the dark, idiosyncratic art song approach that made “Is That All There Is?” a game changer.

Mirrors’ highlight “Tango” had twin inspirations: The brutal, unsolved 1968 murder of actor Ramon Novarro, and the music of Argentinian tango pioneer Astor Piazzolla. The dissonant, downright spooky “The Case of M.J.,” meanwhile, was inspired by Truman Capote’s unsettling story of isolation and madness, “Miriam.” The circus-themed anti-war allegory “Professor Hauptmann’s Performing Dogs” triangulates a course somewhere between Brecht/Weill, Newman, and The Beatles’ “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite.” Upon hearing a couple of tracks, A&M exec Gil Friesen remarked, “They’re too weird but they’re brilliant.”

The sessions, like the songs, did not overflow with sunlight and roses. At various points, Lee temporarily barred both Leiber and Stoller from the studio. But the culmination of the voyage was worth the choppy seas they all endured. Stoller reckoned that Johnny Mandel’s arrangements “created the perfect settings for Peggy to prove that she could be as unique and important a cabaret singer as Edith Piaf or Jacques Brel.”

Mirrors was as anomalous in the musical landscape of 1975 as “Is That All There Is?” had been in 1969. Unfortunately, its uniqueness didn’t precipitate the same commercial success. But long after its emergence, Leiber still steadfastly stated, “Mirrors is an important piece of work.” And Stoller said, “Years later, traveling in Europe, I discovered that certain cults had formed around Mirrors.” To his delight, he found that among these aficionados he and his partner were more respected for that album than for any of their rock ‘n’ roll blockbusters.