How Berry Gordy And Motown Pioneered African-American Businesses

From a tiny $800 loan, Berry Gordy turned Motown into the biggest African-American business of its era, paving the way for black-owned labels that followed.

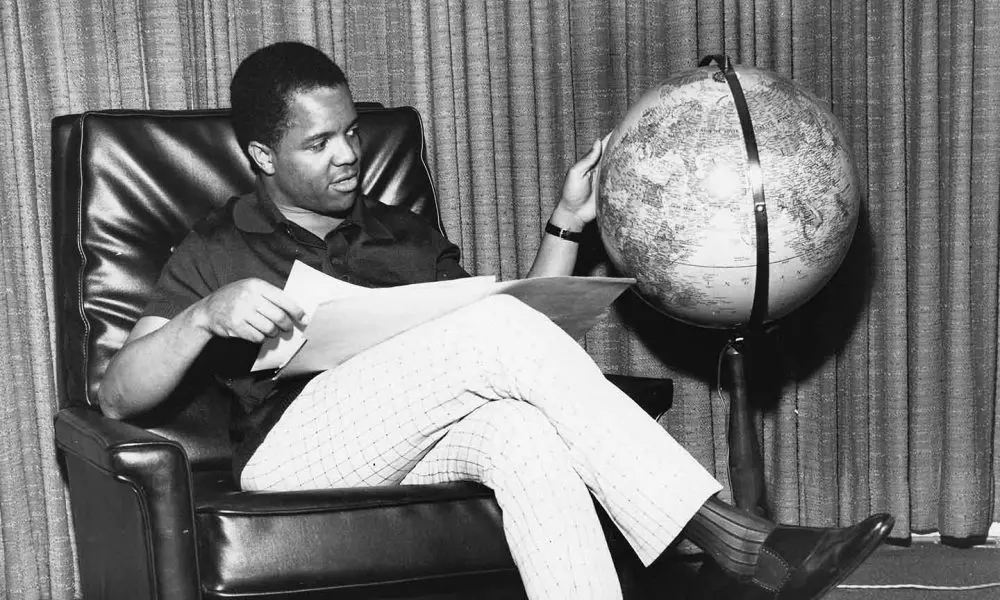

Famously, Berry Gordy borrowed $800 to launch the biggest African-American-owned business of its era. Considering that his background included boxing, running a record shop that went bust and fitting upholstery on a car assembly line, it was quite an achievement. But the Detroit dynamo’s success was built on firm business principles which the many record companies who dreamt of becoming “the new Motown” would have done well to follow. Berry Gordy worked out a way of beating the odds when they were always stacked against black people in 60s US – without him, there’d be no P Diddy or Jay Z. Here’s how he did it.

Listen to the best of Motown on Apple Music and Spotify.

Go for what you know

In the mid-50s Berry Gordy had run a record shop, the 3-D Record Mart. He’d also become a successful songwriter, penning hits for prototype soul star Jackie Wilson. Had Gordy entered the booze trade or opened a boutique, he would probably have failed. But music was his passion. He was cut out for it.

Talent comes first

A record label that signs mediocre artists will always be mediocre. Gordy’s first instinct was to employ the most brilliant people he could find. He was an active talent-spotter throughout his career, supporting young artists that he believed had the fundamentals to find success, from singers such as The Supremes and Commodores to songwriters such as Ashford & Simpson and Willie Hutch. Gordy knew that some of the acts he signed probably wouldn’t become stars but, given time in the right environment, could develop into important writers or producers. Other companies, such as Dick Griffey’s Solar, followed this example.

Be discerning

Smokey Robinson wrote 100 songs before he had one accepted by Gordy. Hence, he had to work hard to be good enough. Jackson 5 had released several singles before Motown signed them, but Gordy had the insight to drive his songwriters and producers to deliver the songs that would fulfill their glittering potential. Gordy had been writing hits since 1957, so knew what it took. He tried never to release substandard material by artists he felt had star quality.

Encourage competition

Motown was packed with people of remarkable ability. Gordy kept them on their toes by making it clear they were not the only show in town. Hence songs were recorded by more than one artist (“I Heard It Through The Grapevine” is an example, with versions by Gladys Knight & The Pips, Bobby Taylor & The Vancouvers and The Miracles being recorded before Marvin Gaye’s definitive reading was released) and sometimes Gordy would set several different producers onto a song and see who delivered the best cut. Motown may have been like a family, but it could be a competitive one at times.

Take control

Gordy owned the means of production. He owned the studio complex, pressing plants, distribution companies and a publishing arm, Jobete, that brought in millions of dollars. Motown didn’t have to rely on other companies to achieve success. Many other black-owned companies tried to emulate Motown by opening, at the very least, their own recording facilities, including All Platinum in New Jersey and Prince’s Paisley Park label and studio.

Hire the best

Gordy used experienced people, black or white, to work behind the scenes at Motown. These included dance tutor Cholly Atkins, who polished Motown stars’ stage moves; Junius Griffin, who’d been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for his work as an editor covering black issues and who became Gordy’s right-hand man in 1967, a time when the company was under pressure from various factions within black politics; promotions supremo Barney Ales; and The Funk Brothers, the superb musicians who delivered, uncredited for years, the astounding grooves that drove the label’s unsurpassed records.

Don’t limit your audience

Motown could have thrived simply by pleasing African-American record-buyers. But it sought a wider, colour-blind fanbase. Its artists recorded show tunes (Marvin Gaye’s Hello Broadway album), R&B (The Marvelettes’ “Please Mr Postman”), socially conscious material (The Supremes’ “Love Child”); dance tunes (Martha & The Vandellas’ “Heat Wave”); love songs (The Miracles’ “Ooo Baby Baby”); and even launched the rock labels Rare Earth, Mowest and Weed. Motown’s stars were trained in deportment, handling the media and dancing, and, in some instances, were encouraged to aim for Vegas. Gordy knew that having his acts join the mainstream would mean their careers and his label would last. The interesting thing is, it wasn’t the label’s easy listening or rock material that delivered Motown’s lasting legacy; it was its soul music. Gordy had the right idea, but didn’t always recognize that pure Motown music had stickability.

Learn from other businesses

Gordy’s work in Detroit’s motor industry made him realize that similar production-line techniques might be deployed at Motown. He had an array of writers and producers churning out top tunes for the label’s artists and the songs were not always fashioned for any particular voice: Barbara Randolph was as likely to record a song as Four Tops. Motown was proud of this and declared itself “Detroit’s other world-famous assembly line.” Also, Gordy saw how other labels had failed, and vowed to avoid their mistakes. Hence, he employed Vee Jay’s former executive Ed Abner and didn’t only use his experience as a record man, but learned from Abner how such a successful label, which once released records by The Beatles, had gone kaput.

Diversify

Once Gordy’s Tamla label was established, he launched further imprints such as Gordy, VIP, Soul, and more, ensuring that radio DJs did not feel they were playing too many records from one company, favoring them too strongly. Other companies, such as All Platinum, Studio One, and Stax, adopted similar tactics. Plus, Gordy moved into other areas, such as music publishing, movies, and TV production, ensuring that all his eggs were not in one soul basket.

Consume your rivals

Rather than tolerate the Golden World and Ric-Tic labels signing talent on his doorstep, Gordy bought out his Detroit rivals, adding Edwin Starr and The Fantastic Four to his roster as a result. He reputedly signed Gladys Knight And The Pips because he realized how brilliant a singer Gladys was and had hitmaking potential that might threaten Diana Ross And The Supremes’… supremacy. Both cut superb hits at the label and their careers still thrived after they moved on.

Don’t forget your roots

Though Gordy became rich beyond his dreams, he did not forget his roots. While cautious about not damaging Motown’s reputation as a company that set out to entertain, he did not ignore developments in the civil-rights struggle during the 60s. Motown acts played at events that raised funds for African-American causes. Gordy had discussions with Coretta Scott-King, the widow of Dr. Martin Luther King, after the Reverend was assassinated in 1968, and donated to the organizations he was associated with. The Motown imprint Black Forum, which was focused on the African-American struggle, opened its catalogue with an album of one of Dr. King’s speeches, Why I Oppose The War In Vietnam. Motown had released two albums of Dr. King’s speeches in 1963.

Even Gordy was not immune to racism: at some of the swankier restaurants he visited in the mid-60s, Motown employees had to phone ahead to ensure that this millionaire entrepreneur would not be turned away at the door through explicit prejudice (or, for that matter, covert: “Sorry, sir, all the tables are booked”). From 1967 onwards, largely through the songwriting of Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong, Motown acts sang about issues that mattered to black people as well as the hip psychedelic youth. These records were hits, bringing titles such as “Message From A Black Man” straight to the ears of fans.

Profit from your errors

Gordy was unsure that Stevie Wonder would make it to star status as an adult, and seriously considered dropping him from the label just before the soul genius was about to launch his astonishing series of 70s albums in 1971. The label head also did not like the sounds coming out of the studio when Marvin Gaye was recording What’s Going On, considering them too jazzy, introspective and unfocused. However, Gordy still released these records and they became lasting hits.

Look around for success

In 1971, Four Tops recorded a song written by Mike Pinder of then-fashionable progressive rockers The Moody Blues, produced by that band’s producer Tony Clarke – an unlikely source of material for a Detroit soul group. But the single went Top 3 in the UK and the Tops also scored with The Left Banke’s “Walk Away Renée” and Tim Hardin’s “If I Were A Carpenter.” Gordy naturally preferred songs published by Motown’s Jobete publishing arm, but he did not prevent his acts from recording other songs, even those from the least-predictable sources.

Trust your ears

You’re the boss. You’ve had lots of hits. You must know a few things. Gordy enlisted Deke Richards to produce Diana Ross’ second solo album, Everything Is Everything. One of the more complex songs featured Ross singing “Doobedood’ndoobe, doobedood’ndoobe, doobedood’ndoo” for its chorus. This gobbeldegook had been used as holding lyrics until Richards came up with the proper words; ever the perfectionist, however, Ross sang this nonsense beautifully. Despite Richard’s protests, Gordy heard it and decided to release the recording as it was, figuring the weird chorus – now also the song’s title – would intrigue people. It certainly worked in the UK, where “Doobedood’ndoobe, Doobedood’ndoobe, Doobedood’ndoo” was a hit single.

Stay close to your artists

Motown’s corporate body was certainly entwined to its acts, writing songs for them, training them, producing them, and working on each one’s distinctive sound. That way, its artists had closer ties to the company culture than those signed to another label who delivered their own material and masters. For some acts, such as The Supremes, Motown effectively controlled their career, vetoing some bookings and directing them to better-paid or more prestigious gigs. When Diana Ross went solo, Motown carefully oversaw the group’s transition to a new sound and personnel. This kind of relationship meant that some acts, such as The Temptations and Four Tops, remained with the label an inordinately long time, delivering hits down the decades. Their names are synonymous with Motown, despite periods spent at other companies. Later, Philadelphia International and Tabu had similar interweaved relationships with their artists, though neither were as all-encompassing as Motown.

Keep your hand in

Berry Gordy’s name appears on around 250 songs in Motown’s catalogue. He kept in touch with what it takes to make a hit.

Above all else…

Motown proved that a black-owned entertainment company could rise to the top of the tree, endure, prove itself superior to its rivals, make a lasting impact on popular culture, develop a unique corporate and artistic identity, and thrive in times of massive turmoil.

All you need is talent, tenacity, a vision, a corporate leader of undoubted genius – and $800.

Discover how Motown broke racial barriers like no other record label.