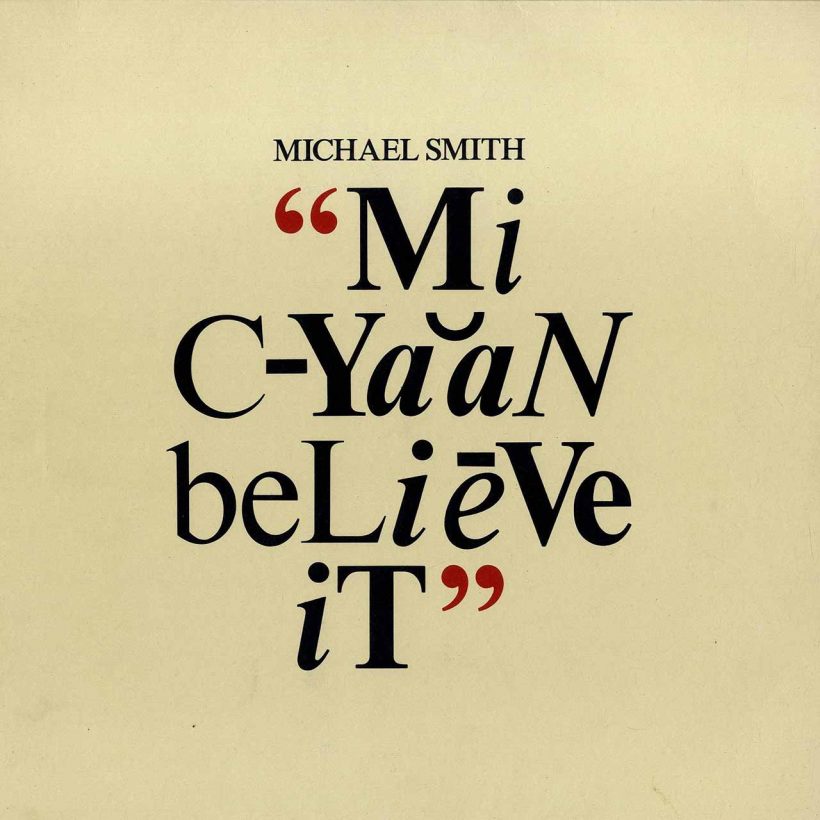

‘Mi Cyaan Believe It’: Michael Smith’s Dub Poetry Touchstone

In a world where conflict, poverty, racism, political oppression, and injustice continue to rule, its messages still resonate.

Fierce. Passionate. Raw. Uncompromising. Those are just some of the adjectives that describe Michael “Mikey” Smith, one of Jamaica’s foremost dub poets. Smith’s life was abruptly ended by his violent murder on the streets of Kingston at the age of 39 in 1983. Though silenced by some who disagreed with him, Smith’s powerful words live on, largely thanks to the enduring brilliance of his solitary solo album, Mi Cyaan Believe It, released by Island Records in 1982.

The son of a stone mason father and factory worker mother, Michael “Mikey” Smith was born in 1954 in Kingston, Jamaica. He felt a natural affinity with poetry as a teenager in the late 1960s when he first began expressing his feelings using rhyming couplets. A spell at the Jamaican School of Drama in the late 70s helped Smith develop his verbal communication skills. There, he cultivated a magnetic on-stage persona, which became an effective tool when he began reciting his poetry in public.

Before Smith graduated, he was already tasting acclaim in Jamaica for his poetry readings in community centers and at political rallies. In 1978, he received international exposure by representing Jamaica at the 11th World Festival of Youth and Students in Cuba. The same year, he made his recording debut, guesting on an independently released 12” single by the Jamaican group Light Of Saba, a mixture of reggae and Afro-disco whose B-side featured his poems “Mi Cyaan Believe It” and “Dem Roots.”

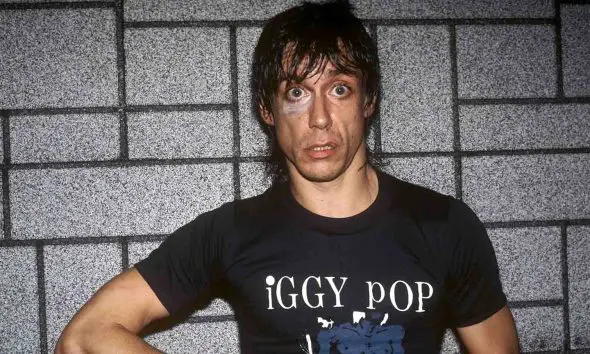

Smith’s growing renown put him on the radar of fellow dub poet, the UK’s Linton Kwesi Johnson, in 1982, who persuaded Chris Blackwell at Island Records to sign him. Johnson, who by then had three acclaimed Island albums to his name, became Smith’s producer together with his valued and much-trusted sidekick engineer/producer Dennis Bovell; the pair’s experience of marrying spoken poetry with dubby reggae grooves made them Smith’s perfect collaborators.

Mi Cyaan Believe It was recorded in London with the multi-talented Bovell playing bass, keyboards, and percussion. On drums was Aswad’s noted tub-thumper, Angus “Drummy Zeb” Gaye. Among the other contributors were guitarist John Kpiaye and flugelhornist Patrick Tenyue, both members of Bovell’s reggae band Matumbi. Together, the musicians created skanking soundscapes with rumbling basslines that were ideal platforms for Smith’s raw poetic eloquence.

The album opened with a short spoken poem, “Black N’ White,” highlighting Smith’s nuanced yet dramatic vocal delivery and skill as an orator. The 30-second piece segued into one of the album’s key tracks, “Mi Feel It,” where Smith painted a vivid portrait of Jamaica in the early 80s over a tense reggae groove. He reflected on the country’s aimless youth struggling to survive in a “concrete jungle” created by an uncaring society where political corruption, inequality, and injustice held sway.

Other highlights included the meditative “Trainer” – featuring Steve Gregory’s dancing flute – the more fluid “It A Come,” which predicted a coming apocalypse over an infectious reggae beat, and the extraordinary “Roots,” a slow, hypnotic percussive number about ancestry where Smith chanted loudly, enunciating the word “Lawd” using long, deep guttural tones.

The keystone of Mi Cyaan Believe It was undoubtedly its spellbinding title piece, a musically unaccompanied performance of a late 70s poem that made Smith famous in Jamaica. Peppered with dry humor and nursery rhyme allusions, it found the poet expressing his incredulity at outrageous situations.

Given its radical mesh of incendiary rhetoric and dubby grooves, Mi Cyaan Believe It wasn’t a huge mainstream commercial success. But the record brought Smith many admirers, especially in the UK. The NME lauded the album, hailing Smith’s “lightness and agility of style that is wholly his own,” also noting the poet’s “hard directness that provides the perfect counterpoint to his almost playful approach to language.” Such was the impact of Mi Cyaan Believe It in Britain that Smith was the subject of a BBC TV documentary. He was championed, too, by DJ John Peel, which led him to record a session for the influential broadcaster’s BBC radio show. Smith also took London by storm with his sold-out poetry readings, arranged to support his album.

Tragically, on August 17, 1983, Smith was stoned to death after an argument with three activists from Jamaica’s right-wing JLF party, in a murder that many people thought was related to his heckling of the country’s Minister of Culture at a political rally.

Smith once said that he regarded poetry as “a vehicle of giving hope,” describing the art form “as part of the whole process of liberation of the people.” He was, then, a true people’s poet, articulating with an unrelenting conviction the hopes and fears of the oppressed and dispossessed and exposing injustice. After his death, his poetry began to be widely published; later, in 2010, he inspired producer DJ Koze to record “Mi Cyaan Believe It” which sampled Smith’s original, and two years later, was the subject of Jamaican composer Peter Ashbourne’s 2012 opera, Mikey.

Though its creator is long gone, Mi Cyaan Believe It remains one of reggae’s most potent collections of dub poetry. In a world where conflict, poverty, racism, political oppression, and injustice continue to rule, its messages still resonate.