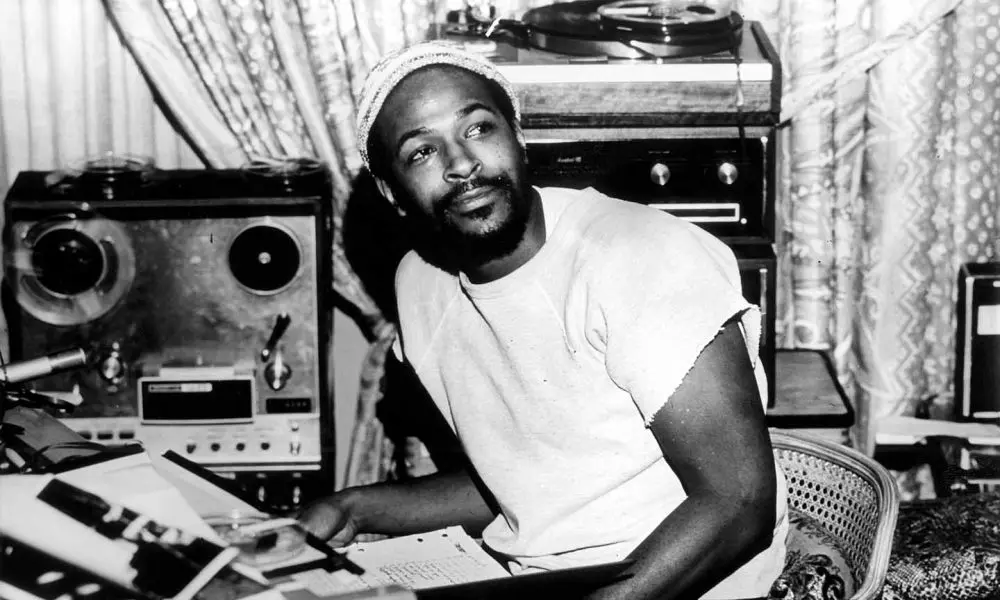

The Soul Of Marvin Gaye: How He Became ‘The Truest Artist’

Hailed as ‘the truest artist’ Motown founder Berry Gordy has ever known, Marvin Gaye was an uncompromising force that defined soul music in the 70s.

Berry Gordy, Jr knows something about artists – of the musical kind at least. When the Motown founder called soul legend Marvin Gaye “the truest artist I’ve ever known. And probably the toughest,” he knew what he was talking about. Gordy spent the best part of two decades working with the man born on April 2, 1939, as Marvin Pentz Gay, Jr.

Gordy witnessed him making some of the greatest soul music ever committed to tape – and some of the most incendiary. He saw the singer fall apart and reassemble himself after the death of his greatest vocal partner, the constituent parts all present, but not necessarily in the same configuration. He saw him become his brother-in-law, then watched Gaye and Anna Gordy’s marriage disintegrate in a manner that was unique, delivering a record that was beautiful and tragic, and probably the first true “divorce album.” He watched him leave Motown, suffering addiction, perhaps hoping that he would one day return to wear his crown as Motown’s greatest male artist – perhaps its greatest, period.

You might expect that there would be suffering in the relationship between the truest artist and the most driven label head, and there was. But what resulted was, at its best, real, unflinching, honest – and, yes, tough and true. Soul music is about heaven and hell, and that’s what Marvin Gaye gave us. More of the former than the latter, but if you don’t know hell, you won’t recognize heaven when you see it.

Listen to the best of Marvin Gaye on Apple Music and Spotify.

In touch with his intimate nature

Marvin suffered for his art, for his soul – and you could hear it. He was not ashamed. He knew no other way that worked. Marvin lived it.

Marvin Gaye’s “realness” was hard-earned. Someone who was so in touch with his intimate nature and feelings probably had no place on stage. The microphone was his confessional, the vocal booth his confession box: this is how I feel, right here, right now.

Trying to replicate that moment to order on tour could be done because he was such a brilliant singer. But this wasn’t really Marvin at his peak, digging in his soul and discovering what was there to let it out. To perform was a different process. You had to put a version of yourself across. But Marvin wasn’t about versions, he was about the authentic moment. Famously, he wasn’t a fabulous dancer and disliked performing enough to suffer from stage fright, though he accepted his role and his performances still marked a peak of his fans’ musical lives. There were many real Marvins over the years, but working as a performer meant he had to learn to let the true one out at any given moment.

Stubborn kind of fellow

Marvin began his musical career singing doo-wop. The first group of note he worked with was Harvey & The New Moonglows. He signed to Motown in early 1961, and his first releases, cut in a style ranging between R&B, swing, and the emergent soul sound, didn’t sell well, though Gaye’s vocal verve was evident from the get-go.

His tendency for introspection while working led to him being told to sing with his eyes open on stage. His headstrong nature meant it took a while for him to realize this was good advice, and unlike other Motown artists, he refused to take lessons in stagecraft and how to deport himself. His fourth single and first hit, 1962’s “Stubborn Kind Of Fellow,” had an element of truth in its title. Perhaps he saw its hit status as a sign that authenticity worked for him.

There was a certain magic about Gaye from the start. His vocal style seemed immediately mature on early hits like “Hitch-Hike,” “Pride And Joy” and “Can I Get A Witness,” and though his voice did develop somewhat, a fan of the older Marvin Gaye would never mistake these records for anybody else. He sounded just as sparkling in a duet, whether this was “Once Upon A Time” alongside Mary Wells or “What Good Am I Without You” with Kim Weston.

Finding himself, wanting more

But while the singles remained alluring and almost automatic chart entries in the US, Marvin’s albums revealed a singer who was not entirely satisfied with life as a young soul star. Marvin wanted more – Marvin always wanted more – and he strove to find himself on a series of albums that, if they weren’t entirely inappropriate, did not play to his strengths. When I’m Alone I Cry and Hello Broadway (1964), and A Tribute To The Great Nat “King” Cole (1965) all found the singer searching for a niche as a jazz – even somewhat middle-of-the-road – vocalist, and while they’re not without appeal, Gaye’s path lay elsewhere.

None of those albums charted, whereas his soul album of the same period, How Sweet It Is To Be Loved By You, sold well, and was packed with exhilarating cuts such as “Try It Baby,” “Baby Don’t You Do It,” “You’re A Wonderful One” and the title track.

It might seem blindingly obvious today where Marvin should have been headed, but in truth, those errant albums were not entirely unexpected: soul was a comparatively new music and nobody knew how long it would last. Many singers took the view that they’d have to work the nightclubs to earn a living, so versatility would be an asset. Motown encouraged this point of view and was perhaps relieved that the uncompromising Marvin was protecting his future when he had already fought against becoming another trained showbusiness-ready star.

A career that would make him a legend

Singing was not the only string to the young Marvin’s bow. He could play several instruments and drummed on successful Motown sessions. He quickly proved a gifted – if not prolific – writer, co-writing “Dancing In The Street” and “Beechwood 4-5789,” big hits for Martha & The Vandellas and The Marvelettes, respectively, plus his own “Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home),” “Pride And Joy” and “Stubborn Kind Of Fellow.” He began to receive credits as a producer in 1965, and in 1966 produced one side of Gladys Knight & The Pips’ debut single at Motown, followed by work with Chris Clark and The Originals. Here were the foundations of a career that would make him a legend.

However, this was by no means a certainty in the mid-60s. Soul music was packed with talent, and though his star quality was evident, Marvin was some way short of being its biggest name. But he was being heard abroad, winning a considerable cult following in the UK, France, and Germany. It was a badge of honor for British mods to own “Can I Get A Witness,” “Ain’t That Peculiar” (1965), and “One More Heartache” (1966), singles that didn’t so much invite you to the dancefloor but practically drag you there kicking, screaming and doing the jerk.

It takes two

But it was Marvin’s work as a duettist that began to cement his status as an established star. Sparring with Kim Weston on “It Takes Two” delivered a big hit in 1966, but when Weston quit Motown the following year, the company found him a new vocal partner who proved an inspired choice.

Tammi Terrell, a former member of James Brown’s revue, had released a few largely under-promoted singles on Motown, but she flourished when working alongside Marvin. Their first album, United (1967), was produced by Harvey Fuqua (the Harvey of The Moonglows, whom Marvin had worked with in his pre-Motown years) and Johnny Bristol. Marvin wrote the modestly successful single “If This World Were Mine,” which Tammi was particularly fond of, and the producers gave them “If I Could Build My Whole World Around You,” but the album’s real humdingers were penned by Motown’s hot new creative team, Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson. Their “Your Precious Love” was United’s biggest hit, but another single proved a breathtaking pinnacle for soul music: “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.”

Practically the definition of soul with ambition, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” takes gospel roots and fuses them with an uptown attitude to create a symphonic whole. If you’re not moved by it, something inside you has died. As a marker for Ashford and Simpson’s arrival at Motown, it was perfect. As proof that Marvin and Tammi had a special magic, it’s unarguable. As a record that helped establish Marvin among the highest echelons of artistic achievement, it was historic.

Initially, Marvin had shrugged about being paired with a third female singing partner, seeing it as more representative of Motown’s commercial focus than his own artistic imperative. At first, Marvin and Tammi learned and recorded the songs separately. It was only when they began working on the tracks together that Marvin realized just how magical their partnership could be. The pair got on like twins. Tammi, a veteran of several gigs a night with James Brown’s band, was a more relaxed and skilled stage performer than her new musical foil. Marvin now no longer had to carry the audience with him alone, putting him at ease in the spotlight for the first time. Success with Tammi set him free as an artist, and his solo records began to take a different, deeper direction.

You’re all I need to get by

With Tammi, Marvin spent much of 1968 in the charts, thanks to the heart-warming “Ain’t Nothing Like The Real Thing,” the glowing and sensitive “You’re All I Need To Get By,” and the buoyant “Keep On Lovin’ Me Honey,” all penned by Ashford & Simpson, who were now handling production duties too. “Oh Tammi,” Marvin wails on the latter, adding, “Ain’t no good without ya, darlin’.” Soon he would know what that would feel like, and the eventual loss of Tammi would affect Marvin profoundly.

In October ’67, Tammi had collapsed into his arms while they were performing in Virginia. She was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor but battled on, returning from the first of several surgeries to record those mighty 1968 duets. Their glorious second album, You’re All I Need, emerged that year, but in ’69 the ailing Tammi retired from live performance.

The construction of the duo’s third and final LP together, Easy, was anything but, with Valerie Simpson helping out on vocals when Tammi was too unwell to sing. The poppy “The Onion Song” and the exhilarating “California Soul” became Marvin and Tammi’s final two hits together. Tammi passed away in March 1970, leaving Marvin bereft.

Soul searching through dark days

The union with Tammi had delivered a steady level of success that took the pressure off Marvin in his solo career – he didn’t have to try so hard to be a success. But his singles, now under the production nous of Norman Whitfield, became darker as his mood was affected by Tammi’s ill health.

His version of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” released in 1968, was far more serious than previous cuts by Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Gladys Knight & The Pips and Bobby Taylor & The Vancouvers, and was a No.1 on both sides of the Atlantic. “Too Busy Thinking About My Baby” found Marvin sounding genuinely mesmerized in his desire. “That’s The Way Love Is” followed up on the troubled mood of “Grapevine,” and his version of Dick Holler’s protest lament “Abraham, Martin And John” was beautifully reflective. This was no longer the quickfire Marvin of the mid-60s giving your soul a buzz; this was a man searching his soul on vinyl. A one-off gospel single, “His Eye Is On The Sparrow,” recorded in ’68 for a tribute album, In Loving Memory, had a longing-for-redemption quality that presaged the music Marvin would be making in the early 70s.

These were dark days for Marvin, despite his success. It’s little wonder that he made such a good job of a song written by Rodger Penzabene, “The End Of Our Road,” a 1970 single; it could have referred to the loss of his singing partner. Penzabene wrote it in 1967 when he was splitting up with his wife, and, sadly, took his own life later that year. Gaye would have known this. But he did not go the same way when Tammi died. Instead, he lost himself in music.

What’s going on?

Marvin was about to reinvent his music, and it took some time for this new sound to gel. The album which emerged from lengthy sessions – and even lengthier debate with Motown’s boss Berry Gordy as to whether it was worth releasing – was regarded as a break with what had gone before, but there had been pointers towards What’s Going On for some time. Marvin’s solo singles from 1968 onwards were increasingly introspective, even though he had not written them. His brother Frankie was fighting in the Vietnam War, which naturally worried the singer; Marvin noted the hippie movement’s protests against the conflict, in which “picket lines and wicked signs” were met by brutal put-downs. His vocals on “Abraham, Martin And John” were apparently sincere, and his performance on “His Eye Is On The Sparrow” showed that he could get that much passion down on plastic if he allowed himself to.

Marvin began to work out some of his musical ideas while producing one of Motown’s undeservedly second-string groups. The Originals had sung back-up on numerous sessions for Motown, including some of Marvin’s, and, despite a lack of hits in their own right, were a truly top-quality vocal act with more than a hint of doo-wop in their DNA. Marvin had co-written their 1968 single “You’re The One,” and its subtle, slightly meandering melody offered hints of the music he would create three years later. Marvin took the production reins for The Originals’ 1969 single “Baby I’m For Real,” and 1970’s “The Bells”/ “I’ll Wait For You” and “We Can Make It Baby.” All are utterly beautiful, and many of the elements of What’s Going On lurk in the layered vocals, dream-like atmosphere, unhurried grooves, get-there-eventually melody, and churning guitars. On these records, Marvin worked alongside several of the figures who’d soon help deliver his definitive early 70s albums, including co-writer James Nyx and arranger David Van DePitte.

A further, and perhaps less likely, influence on Marvin’s new direction was Renaldo “Obie” Benson, one of the Four Tops, whose 1970 single “Still Water (Love),” co-written by Smokey Robinson and its producer Frank Wilson, bore many of the audio and even lyrical hallmarks of What’s Going On. Benson, not known as a writer until this point, went to Marvin with ideas that became, with his collaboration, the title track of What’s Going On and two further vital songs, “Save The Children” and “Wholy Holy.”

Marvin’s landmark album slowly came together, and despite Berry Gordy’s doubts – he saw it as too jazzy, rambling, and non-commercial – it emerged in May 1971. What’s Going On met enduring critical acclaim, contemporary approval in numerous cover versions of several of its songs, and, importantly for Marvin, as it proved his vision could be marketed, the album went Top 10 in the US.

He had made his full undiluted statement at last, writing, producing, and establishing himself as a serious artist who still sold records. What’s Going On delivered three substantial hit singles. Doubts? Gordy was happy to be proved wrong.

You’re the man

But the path of true talent never runs smooth. Marvin’s first single from his next project, “You’re The Man,” was fabulous – but not commercial, and it stalled at No.50 in the Billboard Hot 100. Feeling the pressure to deliver a record on a par with his masterpiece, the highly politicized album of the same title was canned. (Released 47 years later, You’re The Man presented a “lost” album of outtakes and scattered sessions that revealed 1972 to be a fascinating transitional period in Gaye’s career.)

Before the year was out, Marvin began work on a fine blaxploitation movie soundtrack instead, Trouble Man, issued that November. By the time a full Marvin Gaye vocal album appeared, the atmosphere in soul had shifted somewhat, and the singer was now focused on giving intimate affairs the intense scrutiny he had previously aimed at the state of the world.

Let’s get it on

Let’s Get It On (1973) was another masterpiece, lush, personal, delightful – even filthy – and initially sold better even than What’s Going On, lingering in the US chart for two years. Two classic albums in three years, plus a highly credible soundtrack: Marvin’s crown remained in place.

However, he was distracted. Two months after Let’s Get It On was released in August ’73, a further album bearing his name appeared: Diana & Marvin, a meeting of early 70s Motown’s commercial giants and Marvin’s final duet album. He had been reluctant to record with another female partner after the death of Tammi Terrell, darkly considering such projects as jinxed since two of his former partners had left the company soon after working together, and Terrell had left the earthly realm. Marvin relented, however, feeling that his profile would increase. The result was a warm, highly soulful record. It could hardly have been any other way.

There were no further studio albums from Marvin until 1976. He was unsure of which direction he should be headed, a mindset not improved by the amount of marijuana he was smoking and the disintegration of his marriage to Anna Gordy Gaye, accelerated by the arrival of a new love in his life, Janis Hunter, who was still in her teens. A gap was filled by 1974’s Marvin Gaye Live! (perhaps surprisingly as the singer had been stricken by stage fright after Terrell’s death) which contained the telling track “Jan” and a stunning version of Let’s Get It On’s “Distant Lover” that became a Top 20 US hit single. His attitude to his past was revealed by a segued version of some of his 60s hits which he titled “Fossil Medley.”

Gaye finally got around to recording a new album, the Leon Ware-produced I Want You, a lubricious songbook of odes to Janis which were as much a part of Ware’s dedication to explicitly erotic soul as they were a step on Gaye’s artistic path. With a funky disco feel, the album still sounds great, though its deep and downbeat boudoir grooves were never going to match to his two previous studio albums for radical impact. You can draw a straight line from the album’s second single, “After The Dance,” and the sexed-up electronica of Gaye’s 80s return “Sexual Healing.”

Got to give it up

In 1978, Marvin delivered Here, My Dear, the reverse side to I Want You in that it was dedicated to his estranged wife, with whom he was engaged in a complex wrangle over maintenance payments, which he apparently could not afford. He agreed to hand over half his royalties for Here, My Dear to the woman who was now the former Mrs Gaye. Unluckily for her, the album did not sell particularly well. Marvin initially resolved not to put a lot of effort into it, as he saw it as a contractual obligation, but the true artist in him surfaced yet again, and what became a double-album turned out to be something of a tour de force, as he got the agony and joy of the relationship off his chest – from first meeting to personal disaster. Marvin sounds a little unfocused in places, but his voice is in beautiful shape and the mellow funky vibe works well. Even the escapist fantasy “A Funky Space Reincarnation” proved a gem.

Prior to this, 1977’s Live At The London Palladium was a decent record, a double set leavened by one studio track, the 11-minute “Got To Give It Up,” which went to No.1 in the US and was as disco as Gaye ever got. It’s still a floor-filler. Another single, 1979’s “Ego Tripping Out,” was neither entirely funk nor disco and was a comparative flop; Marvin refined it for months but then abandoned the album it was meant to be on, to Motown’s chagrin. His last LP for the company, In Our Lifetime, included more material inspired by a failed relationship, this time his marriage to Janis. Having been stung by Marv’s failure to deliver his previous album, Motown reworked some of the tracks on In Our Lifetime and rushed it out before Marvin had finished it. But do not assume that it’s below par: this a Marvin Gaye album we’re talking about. Intended at least partly as a philosophical and religious treatise, it’s an absorbing, funky, and soulful affair. “Praise” and “Heavy Love Affair” in particular are top-notch tunes.

Marvin Gaye was soul music

On a personal level, the wheels were coming off for Marvin. He was being pursued for millions of dollars in unpaid taxes. He had a drug problem and had moved to Hawaii, London, and Ostend, in Belgium, to try to shake off financial pursuers and his demons. Having quit Motown, he signed to Columbia, cleaned up his act to some degree, and began work on tracks in his Ostend flat with the keyboard player Odell Brown, who’d cut six albums as a jazz organist. The result was the all-electronic single “Sexual Healing,” released in September 1982 and a worldwide smash. An album, Midnight Love, was well-received, and Marvin went on tour. Back in the thick of it, his cocaine use increased and the sick, tired singer went to stay with his parents in Los Angeles at the end of the tour.

On April 1, 1984, after a family argument, Marvin was shot dead by his father, a shocking end for anyone, but especially for a singer who always sang of love, often of peace, of spirituality and sensuality, and who tried his utmost to stick to his artistic mission even when he knew he was failing to live up to the ideals he craved for himself.

The truest artist? These things are impossible to quantify. But when you hear the best of his work, you know Marvin Gaye was serious about what he did, and that expressing his true feelings and nature was the only way he could function as an artist. More than this, even the worst of his work makes you realize he was still trying to deliver what was in the core of his being. That is true artistry. That is soul music. Marvin Gaye was soul music.

The lost Marvin Gaye album, You’re The Man, can be bought here.