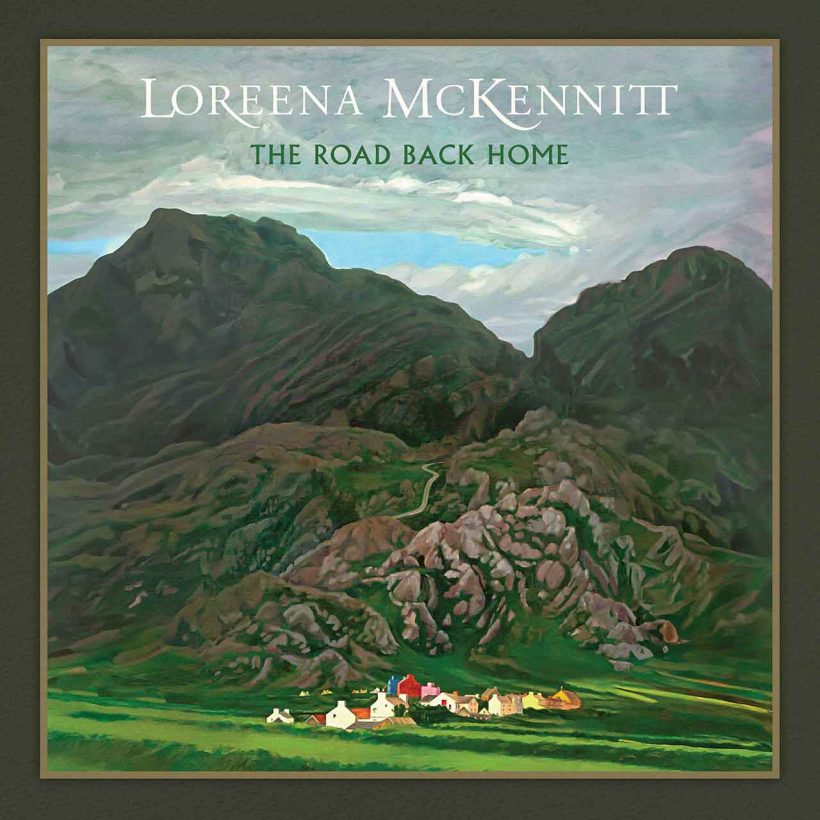

Loreena McKennitt Interview: Taking ‘The Road Back Home’

The Juno-award winning Canadian singer and composer reflects on her remarkable career.

Since self-releasing her first album Elemental back in 1985, Loreena McKennitt has done things her own way. Hers is a genuine grassroots success story, as her unique sound – a reflection of the multi-faceted music of the Celtic diaspora – won her a devoted fanbase, which grew with each release. 1991’s The Visit was her commercial breakthrough, which she followed with her biggest-selling albums The Mask And Mirror (1994) and The Book Of Secrets (1997). More recently, she was on the road, performing anniversary concerts for The Visit and The Mask And Mirror across Europe.

Her recent album, The Road Back Home, is a spontaneous live recording culled from a series of shows in 2023 in which McKennitt returned to the traditional songs that she busked as a musician finding her way. In a new interview, she reflected on a life in music.

How did your album, The Road Back Home, come about?

Essentially, it’s an accidental recording. We had intended to do a European tour last summer. But because the lead time of building these tours is about a year and I wasn’t sure which direction Covid was going, we postponed Europe until this summer.

So we had this empty summer, and I said to my colleagues, “I wonder if we got together with this local Celtic group, The Bookends, to work on a 60-minute set,” as some of the local folk festivals had been asking me to perform over the years and I hadn’t been able to. So we just put our musical minds together and came up with a set. Then I thought, ‘Maybe we should actually record these as well.’ In a way, it’s more of a field recording than a traditional live recording as we didn’t have control of many things. It happens, particularly with outdoor live performances. I have great respect for life and the world stepping in [laughs] and adding its own contributions, so long as it’s not too devastating.

Did that time away from touring give you a renewed appreciation of what the songs mean to you and your audience?

Yes, to some degree. It’s kind of like a racehorse, you’re built for something. And then, when you’re not running anymore, you think part of the fabric of who you are is missing. During Covid I was very lucky, we live on a farm and could get on with many other things. I was also heavily involved in a big civic episode here in Stratford, Ontario. The city was planning for a huge glass factory and I was a leading player in coordinating rallies and speeches and speakers. That was a big civic battle – which we won, I’m happy to say.

You’ve returned to “Bonny Portmore” on The Road Back Home. How important do you think songs are in keeping a sense of history alive?

I have such passion for the natural world and connecting the dots of the climate emergency that we’re in, that when I came across “Bonny Portmore”, I thought, ‘Wow, this is an important piece.’ Not just for the story of a handsome tree being taken down. The other verses were lamenting how many other trees may be taken down for shipbuilding purposes and the loss of habitat. So this is a hugely contemporary subject. And it has a Canadian dimension, because there were a lot of trees cut down here in Ontario and Quebec to support shipbuilding. So I feel it’s a real connection from the past to the present that still has incredible relevance, from the loss of the habitat to how that plays into biodiversity. So it’s one of those pieces I feel passionate about.

What role did music play during your formative years?

I started learning the piano at age five. My teacher made a prerequisite that all her students were part of her children’s choir. It was a very good one, and we competed in provincial competitions. So, before I could even read words or music, I was singing, and all those brain-ear synapses were being built. I still use a lot of my classical training in how I sing and protect my voice, but also the phrasing and the dynamics. So even though I’m not performing classical music, I’m still trading in it.

When did more traditional music begin to interest you?

When I lived in Winnipeg, I was introduced to more folk music and attended a club on the main street. We’d get together on Sunday nights in this woodwork shop, there would be people from Ireland, Scotland and England, and we’d bring in albums, swap them, and learn pieces. That’s when I became really inspired. It was like love at first listen.

Then I realized that it was impossible to appreciate folk music without taking into account the political, economic, and social circumstances from which it sprang. I took a course in Irish history, it was very important for me to get a deeper appreciation of Irish music, history, politics, and everything that went back to at least the Act of Union in 1800 and the shipbuilding industry which denuded the country.

Then, in 1991 I attended an exhibition in Venice (The Celts – The First Europe, held in the Palazzo Grassi on the Grand Canal) which was the most extensive ever assembled on the Celts. And I realized that they were this vast collection of tribes that had fanned out across Europe and into Asia Minor.

I looked around and thought, ‘Well, there’s a whole bunch of other musicians who are performing traditional music far better than I could, so I’m going to go and explore the history of the Celts, and maybe write some original material inspired by that.’ And that informed the greater part of my career to date. The Road Back Home really is like going back to Winnipeg in the 1970s, to that folk club in that time, and a few years after that, where I was busking on the streets of Toronto and Vancouver.

How valuable were those early years of busking in instilling a DIY ethos?

I’d like to say it was all planned but, of course, it wasn’t. It was more, “well, what can I do?” In 1985, I borrowed the money my family had saved for my university veterinarian studies, and I made my first recording. I ran off 30 cassettes, gave 15 of them away, and then didn’t know what to do with the rest, so went busking in the St Lawrence Market in Toronto.

I was poor as a pauper, still borrowing a bit of money from my parents, and I was already in my late 20s. It was quite humiliating in some ways to be defining myself in that way and going busking in Toronto, because so many people here saw that as a glorified way of begging. But it was a fascinating thing, because I would play these 20-minute sets – “Mary And The Soldier” was one song, “Sí Bheag, Sí Mhór “was another – and people would stop and listen. I’d chat with them, sell them my cassettes and raised enough money to make my second recording in ’87, then started going on tour. Stores would phone directory assistance for Stratford and say, “Do you have a phone number for Loreena McKennitt?” And they’d call me and say, “We’ve got people asking for your cassettes, would you sell us some or would you give us some on consignment?” So I learned that part of it. And I would go and ship my little cassette boxes off to various places that I would be travelling to, touring with my little harp across Canada. It was a real grassroots thing.

When you look back, is there anything you’d do differently?

I’m not sure I would, I was clearly listening to something very central in my being. As things evolved, I learned more about the music industry and how many factors contributed to success, in terms of business and promotion. During that whole grassroots effort from 1985 – particularly when I signed a licensing deal with the Warner Music Group in ’91 – I learned a lot just by rolling up my sleeves and doing it brick by brick. I developed the capacity to always finance my recordings. To this day, I never had to borrow money from the record company for the recordings or for touring or videos, I was always self-sustaining. I’d love to say I knew what I was doing, but I didn’t. I sometimes think it’s a very Celtic thing, a stubbornness, a bloody mindedness – you’re not going to be anybody’s baby, you’re going to work really hard doing your thing and hope it pays off.

As things took off, was writing your own material daunting?

It was. I still would still say I’m a very insecure writer. An example of that occurred when I was working on The Book Of Secrets at Real World, Peter Gabriel’s studio in Box, near Bath. I’d go into the studio and wouldn’t have always have all the material written. So I holed up and made a little writing corner in an isolation booth. I would set the engineer on some housekeeping tasks, and I would keep writing [laughs]. I was working on the beginnings of “The Mummer’s Dance” and I asked Hugh Marsh, the fiddler, “Hey Hugh, do you think I should even continue working on this piece?” “Well, yeah, I think you should keep working on it!” And it ended up being huge, for me anyway.

And how about balancing that with traditional material?

It was a gradual process. My third album, Parallel Dreams (1989) was really the first time where I thought, ‘OK, how much traditional material can or should I do? And what am I going to write about?’ So that was a very tenuous recording. The litmus test was – whether it was through busking or these grassroots performances I was doing across Canada – that I was selling quite a number of recordings, so there was clearly an appetite for the quirky thing that I was doing, which gave me more confidence.

And then later, working with a major record company with the deal structure I had meant they weren’t taking on a big risk, because I was always financing my own recordings. So no matter how quirky it was, they weren’t terribly worried. When I played them “The Lady Of Shalott” from The Visit, which is nearly 12 minutes long, I’m thinking well, they may think they’re absolutely out of their mind to sign someone like me!

The Visit also features an unusual take on “Greensleeves,” how did that come about?

The engineer was on the telephone having a chat. And I said to Brian [Hughes], “I wonder how Tom Waits would do ‘Greensleeves’?” We were just fooling around. And then the engineer got off the phone. And he said, as good engineers do, “That sounds interesting. Why don’t you try that all over again and I’ll just press record?”

How did the success of The Visit change things for you?

It was exciting, because I finally had a bit more money to be able to start painting creatively and exploring this fusion of uilleann pipes, udu drums, sitars and different combinations of things. After that exhibition in Venice, it became very clear in my mind what I needed to do. And that was to travel to as many of those geographical places that the Celts had been and learn about the history and the broader context of that. I didn’t feel like everything I wrote had to explicitly be directly connected to the Celts, but rather it’s like going on this road where you allow yourself to wander off it and explore and learn things then come back. Then I felt you can’t really appreciate Spain without taking into account Morocco.

Visiting Morocco must’ve been a memorable experience…

I’d never been to a Muslim country before and this was back in ’93, it was still a fairly raw place. I arrived on the evening of Ramadan. Everything I was seeing, hearing, smelling was so different. And then, of course, the aesthetic of going into the desert, and the sky and the sunrise over the dunes. We were there during daylight and met some people who were going to play music for us, we went back to the place we were staying and then tried to come back in the evening. But there was no road. We had to follow telephone lines and this light in the distance going back and forth. And they saw the headlights of the car kind of weaving around. And so, some of that imagery I wove into “The Mystic’s Dream”.

For probably every single song I’ve written and maybe even recorded, there’s a very particular picture in my mind’s eye that became like ballast in the studio. There are so many creative directions you can go in, but I’d say, “Oh no, I have to paint this picture.” And that would keep me anchored. I’m always thinking very cinematically; I’m trying to set the arrangement in a particular time and place. With “The Gates Of Istanbul” from An Ancient Muse I had a very particular picture in my mind and one element of that was a heat mirage. I said to Hugh Marsh in the studio, “Can we come up with a sound that emulates that that mirage?” And so he played around with some violin and added effects and I said, “Oh, that’s it right there. That’s the mirage that’s going above the sand.” It’s a crazy way to work.

Do you still see those visuals when you’re performing those songs on stage?

Often I draw upon them on stage to make sure that my mind doesn’t wander to some pragmatic thing. I worked in the theatre for long enough exploring acting and learned some of the discipline of what you have to do before you go on the stage. And that is losing yourself in the part. It’s too easy when the pieces become so familiar that you could do them with your eyes closed. You start thinking, ‘OK, what am I going to have for breakfast or what’s going on back home?’ I just won’t allow myself to do that. So being able to focus on the imagery, and get lost in that imagery and get inspired by the imagery over again is central to being able to perform in as fresh a way possible each night.

How much did you enjoy going back on the road for The Visit and The Mask And Mirror anniversary shows?

When you’ve become a deliverer of music, and you realize how much this means to other people, you realize that the whole experience isn’t complete until you’ve shared it. It is like making a meal – you can cook all you like at home, but if you don’t have somebody to serve it to, what’s the point? So we always feel very excited and grateful to get back together. And the musicians that I’m working with are just superb. I’ve worked with them for so many years, we all know each other, our creative instincts are aligned. And it’s always great meeting the audiences. I see touring as more of an athletic event than an artistic one. It’s endurance. And there are the mental things you have to deal with. Because you get exhausted mentally sometimes, and you just want to go home to your bed. But you have to work through all those things. It’s about being an adult, I’m sure many other people do it in their careers! [laughs]

And your shows end on a note of joyful communion…

At the very end, I say, “And now’s your turn. Some of you may know this, some of you may not. But it’s not very complicated. And if you can sing with me, it’ll be just a joyous thing.” Then I teach the crowd to sing “Wild Mountain Thyme”, I’ve printed the lyrics in the program. It’s a way to reclaim that exquisite feeling of sharing music together. And to remind people, music doesn’t have to be this spectator sport, where you are relegated as an audience member, and you sit there and you politely clap. Music is this incredible universal language, there’s nothing like it.

For me, the most glorious moment of the whole evening was hearing those people get out of their shyness or their reticence and communally sing. This is something we can actually all feel together. We’re not in our little cylinders of our smartphones and our social media and all that bullshit. It’s like, no, no, we’re going to find our common humanity here for just this brief moment!