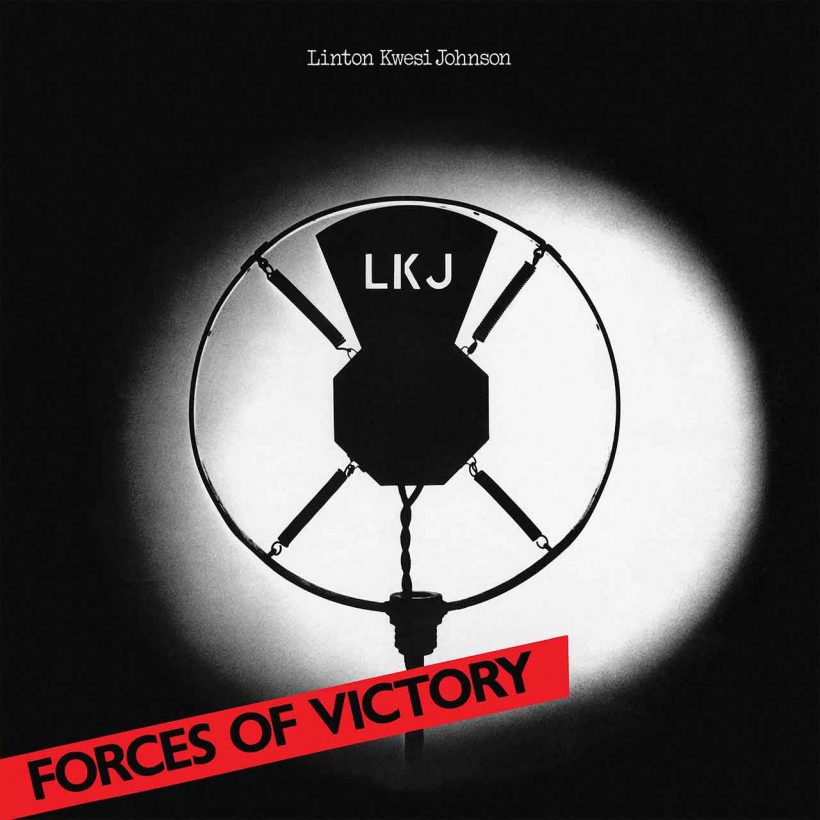

‘Forces Of Victory’: Linton Kwesi Johnson’s Radical Reggae Landmark

The album was hailed in 2003 by David Bowie as ‘one of the most important reggae records of all time.’

First impressing as the resonant-voiced frontman of Poet And The Roots on the 1978 album Dread Beat An’ Blood, political activist-turned-poet-and-essayist Linton Kwesi Johnson emerged as a solo artist a year later with Forces Of Victory, his debut for Chris Blackwell’s Island label. Hailed in 2003 by David Bowie as “one of the most important reggae records of all time,” Forces Of Victory is widely regarded as a landmark record, not only in the history of British Afro-Caribbean music but also in the reggae genre generally.

Born in Jamaica, Johnson moved to London’s Brixton area when he was 11. He began writing poetry at school in the late 60s around the same time he joined the British Black Panther movement. “I began to write verse, not only because I liked it, but because it was a way of expressing the anger, the passion of the youth of my generation in terms of our struggle against racial oppression,” Johnson later told The Guardian. “Poetry was a cultural weapon in the black liberation struggle, so that’s how it began.”

By the mid-70s, Johnson was a published poet; his second volume of verse, 1975’s Dread Beat An’ Blood became the basis of a same-titled album, made with the innovative Barbados-born sound engineer and producer Dennis “Blackbeard” Bovell, leader of the British reggae group Matumbi who was also the mastermind behind the Poet And The Roots’ project. Bovell’s skill in creating spacey dub mixes, defined by shifting textures, echoing sound effects, and fractured instrumental parts, seemed the ideal backdrop for Johnson’s sonorous monotone voice.

Delivering his words in a rich Jamaican patois, Johnson found the perfect foil in Bovell. Across eight mesmerizing tracks laced with horns, the pair created a series of immersive soundscapes on Forces Of Victory that drew the listener into a gritty world of social unrest, urban angst, and racial oppression. With his ear close to the street, Johnson vividly articulated the Black Afro-Caribbean experience in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, giving voice to both a disenfranchised and disillusioned generation.

The album’s keystone was the solemn and intensely powerful “Sonny’s Letter (Anti-Sus Poem),” where Johnson related the story of a young Black man writing to his mother from prison explaining how he killed a policeman in defense of his younger brother during an unprovoked attack by the police while waiting for a bus. The track protested against the “sus” law in the UK, often used to target racial minorities, which allowed the police to stop and search a person they suspected of wrongdoing.

Elsewhere on Forces Of Victory, Johnson espoused direct action against racist provocateurs in the shape of “Fite Dem Back” – distinguished by the memorable chorus line “We gonna smash their brains in” – and offered a riposte to those complaining about the antics of young people with “It Noh Funny,” which allowed Bovell to indulge his love of dubby sound textures.

The persistent “Independent Intavenshan” expressed Johnson’s sense of isolation as an Afro-Caribbean and found him despairing of Britain’s political parties, to whom he felt no allegiance. Forces Of Victory ended on an ominous note with the righteous “Time Come,” driven by insistent horn fanfares, which prophesied revenge on the oppressors. “It too late now,” declared Johnson, promising a day of reckoning. “I did warn yu.”

With its claustrophobic tales of inner-city tension, Forces Of Victory introduced a radical new voice – one that vividly brought alive the racial polarization of late 70s Britain, where simmering tensions would soon reach boiling point and spill over into riots and public disorder. The album was released by Island in the summer of 1979, earning widespread critical acclaim. Rave press reviews were quickly converted into impressive sales figures, helping the album to rise to No. 66 in the UK LPs chart.

Johnson would make four more albums for Island, two of which, 1980’s Bass Culture and 1984’s Making History, also tasted mainstream success. But for its ingenious marriage of words and rhythms, Forces of Victory represented the artistic pinnacle of his work for Chris Blackwell’s label. Though the record reverberated with perceptible echoes of Jamaica’s “toasting” tradition, when DJs would rap and chant over records, Johnson had created something deeply original and exciting. It was a record that fuelled the emergence of other dub poets, like Jamaica’s Mutabaruka, Mikey Smith, Oku Onuora, and Jean “Binta” Breeze, plus more recently, the British-Caribbean wordsmith Anthony Joseph.

“Linton’s fiercely articulate politicized commentaries formed an important link between the toasting of Big Youth and U-Roy and rap,” observed Chris Blackwell in his memoir The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond, acknowledging Johnson’s unique talent. “(His) records definitively proved that British Jamaican music was in no way inferior to the very best and most adventurous Jamaican reggae.”