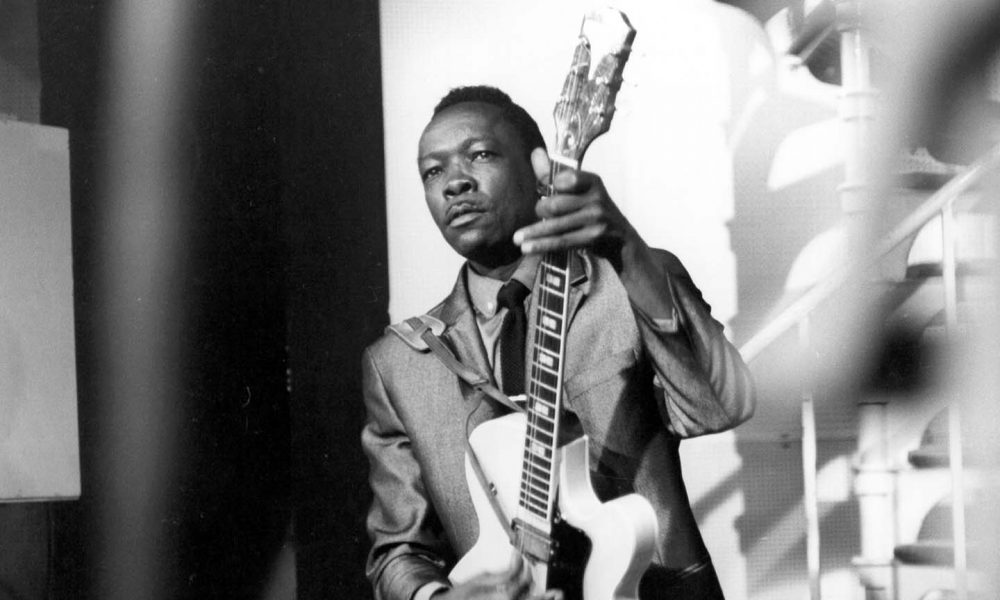

Best John Lee Hooker Songs: 20 Essential Tracks By The Blues Legend

The best John Lee Hooker songs find an imitiable groove to prove that the blues could make you feel, but it could also make you dance.

He couldn’t boast the effortless authority of Muddy Waters. He wasn’t an outlandish marketable character like Bo Diddley. He couldn’t terrify you from across the hall like Howlin’ Wolf. But John Lee Hooker was a blues survivor who’d rock you to the socks that were poking out of the hole in your soles; he was street-smart, adaptable, even crafty. And armed with nothing but a guitar and his dark, moody, mumblin’, barking voice, he’d make you dance: “Boogie Chillen,” as he once called it. And that’s where we’ll start our rundown of the best John Lee Hooker songs, because this was his debut single. This 1948 anthem is a call to get ya dance freak on. Oh, but isn’t the blues a noble cry of the poor African-American who is suffering? Hell yes, but Hooker’s telling us if you got feet, you can use them to beat the blues.

Listen to the best John Lee Hooker songs on Spotify.

Hooker, born on August 22, 1917, the youngest of 11 children to a sharecropping (a smallholding farmer) Baptist preacher in Mississippi, didn’t need lessons in being poor. He was raised to be God-fearing, but this changed when his parents split up in 1921, when he was nine (though accounts of Hooker’s birth date differ). His mother married again, to William Moore, a blues guitarist who handled his instrument in a droning, insistent style, which his stepson would adapt into a method he later half-parodied in his 1971 song “Endless Boogie, Parts 27 & 28” – though Hooker was anything but a musical stereotype, as we shall see. While John Lee was a juvenile, his sister took up with another bluesman, Tony Hollins, who gave him a guitar and taught him songs that would serve the kid all his days. Among them was an essential track for every John Lee Hooker playlist, ”Crawlin’ King Snake,” which Hooker first recorded in 1949 – and copyrighted. Hence when rock came along and the likes of The Doors covered it on LA Woman in 1971, John Lee Hooker done got paid. The same goes for the times he recorded it himself, of which there were many.

Hooker left home when he was 14, and never looked back. In fact he never came back, and never saw his ma and stepdad again. He turned up in Memphis, where he scuffled for a living and played at house parties by night. He joined the exodus of southern folk moving north in search of work, finding it at Ford in Detroit during the Second World War, his factory job bringing in enough bread to replace his acoustic guitar with an electric one. He was now loud enough to compete with city life, and became a regular performer in clubs on Detroit’s East Side. A demo made its way to Modern Records in LA, which released “Boogie Chillen.” It was an R&B chart No.1 and Hooker’s career was underway.

“Hobo Blues” followed, another R&B chart hit, and Hooker seemed determined to follow a nomadic path himself, drifting from record label to record label, depending on where the next cheque was most likely to come from. He worked for King out of Cincinnati as Texas Slim, Regent/Savoy as Delta John, and for smaller labels as Birmingham Sam and The Boogie Man; but you’d have to be deaf not to recognize him on these sides. The label-hopping went on: seems like everyone with a dollar to spare landed a Hooker record to release. Modern enjoyed another R&B chart-topper in 1951 with “I’m In The Mood” (a lewd ditty Hooker recorded eight times over the years and which tempted Bonnie Raitt into a duet with him decades later), and then he was off again, working with the Chicago label Chess, which got sued by Modern in 1952 over the single “Ground Hog Blues.” The thing is, John Lee was a star: his hard-rocking boogie style was hard to replicate, and that made him worth fighting over. Modern finally bowed out of his increasingly tangled career in 1955 with the single “I’m Ready.” If it had known what was around the corner, it might not have quit.

Signing to Vee-Jay, Hooker issued “Dimples” in 1956. By now he was recording with a full band and this easy-rolling hit about an attractive woman enjoyed an extended afterlife. In 1959, Vee-Jay realized the burgeoning folk boom in the US might provide Hooker with an opportunity, and also realized that it was not the label to facilitate it, so it licensed Hooker out to the New York company Riverside, which extended Hooker’s reach into a white audience through two albums, the first of which, The Country Blues Of, included another John Lee Hooker playlist staple, “Tupelo Blues”: a much-revisited song about a flood in the Mississippi town Elvis Presley had been born in. The song possessed a sense of history just like “Natchez Burning” had for Howlin’ Wolf, establishing Hooker as a man with roots.

Another notable Riverside session delivered “I’m Gonna Use My Rod,” later retitled “I’m Bad Like Jesse James” and “I’m Mad Again.” Hooker seemed fine with being portrayed as a folk singer, despite his gun-totin’ lyric, which was hardly peace and love. Was he gettin’ paid? Then call him what you like – he’d already changed his name numerous times on record. Should you be in any doubt as to his credibility with the folk crowd, Hooker played in New York in 1961 – and the support act was Bob Dylan, making his debut in the big city.

Folk was not the only new market opening up for Hooker. In London, rhythm’n’blues was rapidly becoming the sound of clubland, and his tunes soundtracked the fashionable dances performed by the original mods. The contemporary “Boom Boom” was certainly no folk ballad: this tough dancefloor-aimed I-fancy-you ditty made the lower reaches of the US pop chart as well as joining a revival of “Dimples” in the mod nightspots in the UK during ’64. The latter was a UK Top 30 hit, and he performed it on Ready Steady Go! on TV. Hooker was moving in soon-to-be-famous circles as he worked with various Supremes, Vandellas and other Motown musicians during ’63-64. Taking this John Lee Hooker playlist in a slightly different direction, ”Frisco Blues,” from an album that attempted to place him in yet another genre, The Big Soul Of John Lee Hooker, may have been a Detroit sound on a Chicago label (Vee-Jay), but the song was inspired by Tony Bennett’s “I Left My Heart In San Francisco.” It was an unlikely source for the blues, but Hooker was always unpredictable and was equally at home on his regretful classic “It Serves Me Right,” aka “It Serves You Right To Suffer,” from 1964.

In 1966, Chess again branded him a traditional artist on The Real Folk Blues, though Hooker was working with a bruising band. The album’s most famous tune, “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer,” has a history dating back to Amos Milburn’s early 50s version, though Hooker imbibed it as he saw fit. Some 18 months on, however, folk was erased from the drinks list and Hooker issued Urban Blues, which included “The Motor City Is Burning,” his comment on the Detroit riots of 1967. Delivering a lyric reflecting the confusion in the city, Hooker conjured up sirens, troops on the streets, snipers, and smoke. This was the blues in an utterly modern context.

By the late 60s, the hippie generation was returning to the roots of rock’n’roll, and Canned Heat, perhaps the band most steeped in Hooker’s boogie style, cut a double-LP with the singer, Hooker’n’Heat, the first of several they’d make together – and the first of his high-profile collaborations to feature on this John Lee Hooker playlist. It featured a fine version of “Whiskey And Wimmen.” To Hooker, it was Groundhog Day: he’d already recorded with white bands he’d inspired, having cut an album in London with The Groundhogs in ’64. They’d named themselves after his “Ground Hog Blues.”

A series of studio albums for ABC ended with Free Beer And Chicken in 1974, which placed Hooker in a funky context with self-explanatory songs such as “Make It Funky,” and the singer issued a slew of live records through to the 80s. His career narrowly missed a major shot in the arm when he appeared in The Blues Brothers (1980), but this version of “Boom Boom” somehow didn’t make the soundtrack album – perhaps there were fears its authenticity might make some of the other tracks look weak. Hooker would have to wait until 1988, when he was apparently 76, for a big revival thanks to The Healer, an album which featured rock stars queuing up to pay homage to their hero on vinyl. Its title track, featuring guitar star Carlos Santana, attracted attention and the record made the US album chart, setting Hooker up for a rewarding old age in both financial and artistic senses

Mr Lucky (1991), produced by Ry Cooder, repeated the trick, with Hooker joined by Keith Richards, Johnny Winter and long-term devotee and collaborator Van Morrison. Upright in suit, tie and hat as ever, the wrinkled Hooker was every bit as convincing as elder statesman as he was in his prime. The awards-laden Chill Out (1995) followed the same formula, with similar guests, but was more reflective, and is represented in this John Lee Hooker playlist with ”We’ll Meet Again” and a mournful version of his 60s song “Deep Blue Sea.”

Hooker’s final album before he passed away, in 2001, was Don’t Look Back, a moving affair that nonetheless still bore his boogie-and-coulda-bin trademarks. The title track might have been ironic, as Hooker was doubtless aware of his impending demise. And he was looking back: he’d recorded the song before, but it had never sounded like this. Now it was a spiritual affair and an apt finale to a unique career – and brings any John Lee Hooker playlist to a fitting close.

The career-spanning 5CD John Lee Hooker box set, King Of The Boogie , can be bought here.