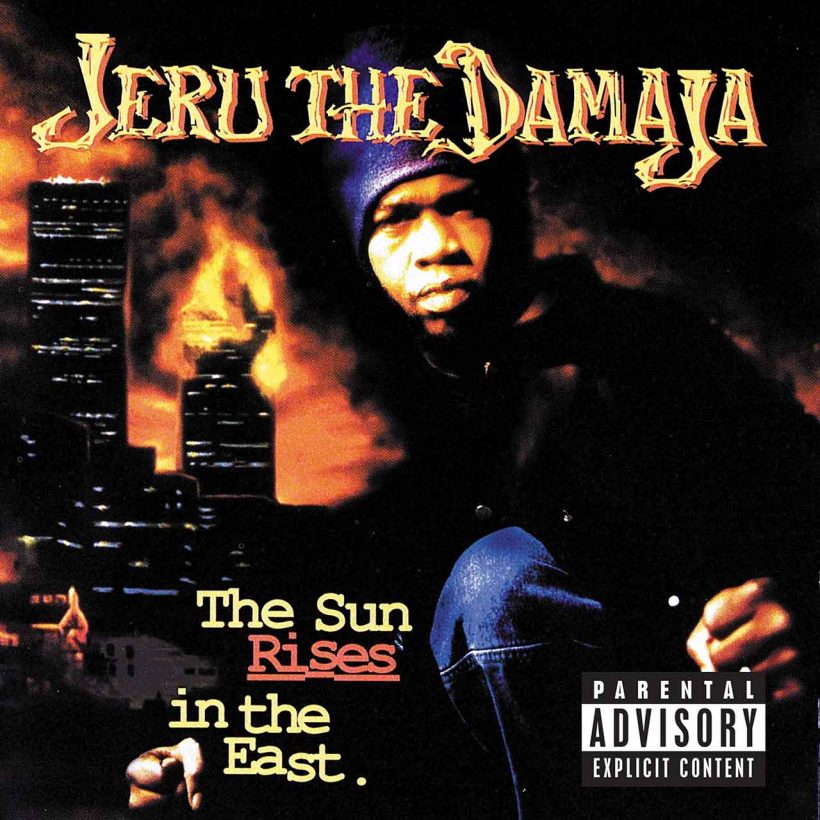

Jeru The Damaja Remembers His Classic Debut ‘The Sun Rises in the East’

Jeru The Damaja sheds light on ‘The Sun Rises in the East’ and his early days with Gang Starr, studio sessions with DJ Premier, and more.

“You wanna front, what? Jump up and get bucked / If you’re feeling lucky-duck then press ya luck…” Those are the immortal bars of Brooklyn’s own prophetic MC Jeru The Damaja, who helped change the landscape of rap in the early 90s with his DJ Premier-produced debut The Sun Rises in the East.

Straight outta East New York, Jeru The Damaja made his first appearance on wax alongside Guru and Lil’ Dap on Gang Starr’s Daily Operation posse cut “I’m The Man.” A year later, he linked up with Premier to put out his first single “Come Clean,” which quickly became a favorite among mixtape and radio DJs in the Big Apple, and led to Jeru inking a solo deal with Payday Records.

Listen to the expanded edition of Jeru The Damaja’s The Sun Rises in the East now.

From there, Jeru and Preemo got down to business, putting in work at the now historic D&D Studios to concoct a debut that would become one of the most defining LPs of the boom bap era. We spoke to the Dirty Rotten Scoundrel himself from his home in Berlin, Germany to reflect on his come-up with Gang Starr, working with DJ Premier in the lab, and so much more, including a breakdown of his relationships with fellow Class of ‘94 legends Nas and The Notorious B.I.G.

You came into the game under the guidance of Gang Starr. How did you initially link up with them?

Jeru: “It was through my high school friends. Gang Starr had a few different incarnations. It started out as Big Shug and Guru – that was the original Gang Starr. Big Shug got locked up, and then Premier came after. So I’ve been around Gang Starr since the beginning. I was in the ‘Manifest’ video.”

Do you remember the first time you ever rapped for them?

Jeru: “We was all homies, just rhyming, and the cypher just evolved. I was hanging out with Guru rhyming all the time. Premier actually gave me the money to put my first demo out. Actually, before that, I did a demo with Guru. We recorded like three songs. This is like ‘89, maybe like two years before I ever recorded anything with Gang Starr.

But the first time I ever really rhymed under the Gang Starr click was on Easter at The Apollo. It was Gang Starr, Rakim, Son of Bazerk, and Main Source. Easter at The Apollo in those days, it was the most ridiculous fashion show – anybody who was anybody was there. Everybody from every borough was at The Apollo on Easter. And I got a chance to spit my freestyle rhyme with them.

It was crazy – the whole Apollo was like, ‘Go Brooklyn, Go Brooklyn!’ I got back to the hood in East New York, and everybody was like, ‘Yo, we heard you killed it at The Apollo!’ That was my first shine on a big level.”

The first time I ever heard you was on “I’m The Man,” which was also your first appearance on a record. Do you remember that initial feeling of what it was like to be featured on a major rap release like that for the first time?

Jeru: “I used to sell books. It was me, the GZA from Wu-Tang Clan, True Master, Masta Killa, my man Afu – we used to sell books in the city. There’s a very famous spot on 6th Avenue in front of Urban Outfitters with a bunch of books out there. We had the very first book stand there on the weekends.

During the week, we’d set up in the Village on John Street. So I was out there one day, and some dude comes by and he’s singing my verse. I’m like, ‘Yo, what you listening to?’ And he’s like, ‘I’m listening to that new Gang Starr album. Some dude Jeru The Damaja. This shit is crazy!’ I’m like, ‘Word?! I gotta get that!’ [Laughs.] It felt good. That’s when I knew it was officially on.”

“Come Clean” was your first single. I love the story about that record – how it came from hearing Premier scratch that Onyx line up while you were on tour with Gang Starr. Can you tell me a little more about how that all came together?

Jeru: Once I got on the Daily Operation record, it was time to go on tour. We did a U.S. tour, and then we went to Europe. I’ll never forget it, because I live in Berlin now, but the first time I came here was December ‘92 with Guru and Premier. RIP Guru – I always gotta thank those brothers for expanding my vision of the world, and helping me to get out of the hood and the hood mentality.

Guru didn’t always go to soundcheck. You paid your dues back then – you’re not an instant superstar. And part of paying your dues was going and setting up. It’s funny because, we used to practice rapping like each other. Me, Guru, we used to have sessions for hours where we would just call out different MCs, and you had to rap like that person. So I’d fake the tonality of Guru’s voice and test the mics out.

So at soundcheck, Premier would always cut up, ‘Uh oh, heads up ‘cause we’re dropping some shit,’ because that Onyx joint had just dropped. And I was like, ‘Yo son, when we get back, we should make a record and use that as the hook.’ And he was like, ‘For real, word. When we get home, I’m gonna make a beat and we’re gonna get on that.'”

Were you already working on solo material with Premier at the time?

Jeru: “Nothing. That was the first song. And back then, everyone was more involved. It’s not like now, with people sending beats online. The way that happened was, Premier was like, ‘Look, I got this drum pattern. Come to my house and let’s figure out something to put on it.'”

And he had the hook, too.

Jeru: “Right. We went to Preem’s house. We listened to like 10, 15 records. And then we heard that Shelly Manne record. And we both looked at each other like, ‘Whoa. Those sounds sound crazy.’ And then Preem was like, ‘You want me to loop it like this, or like this?’ He looped it, he put it on a cassette, I threw it in my man’s truck on the way home, and that’s when I came up with the first line. I went home, wrote the rhyme, and we recorded it.”

So “Come Clean” blows up. Does that directly lead to you getting the deal with Payday?

Jeru: “We put the record out ourselves. Guru had his own label, Ill Kid Records. And he did a Gang Starr Foundation sampler. A lot of people talk about Gang Starr Foundation – that’s me, Shug, and Group Home. We made that name up. Because at the time, we went on tour with EPMD, and they had the Hit Squad. So we were like, ‘We gotta call ourselves something. We just can’t be the homies who’s hanging around.’

So we put that sampler out, and it had ‘Come Clean’ on it, a song by Big Shug called ‘Stripped and Pistol Whipped,’ and a song by Group Home called ‘So Called Friends.’ We paid the promo dude and he sent it out to all the DJs. So we’re chillin’ in the Village and I hear my song comin’ out a car. I said to my man, we getting high and shit, ‘Yo son, you hear that shit? I just heard ‘Come Clean’ coming out of a car.’ He’s like, ‘Yo son, you’re buggin’.’ And then three minutes later, it came out another car! But this time, the car stopped at the light and motherfuckers heard it. And they don’t got no tape, so it’s gotta be on the radio.

To be honest, I could’ve gotta deal on any record label at the time. They was all coming at me. I decided to go on Payday because Patrick [Moxey] was working with Guru and Premier, he was their manager. We was trying to keep it in-house.”

Payday had a pretty ill lineup. You, they had Jay for a second, Showbiz and A.G.

Jeru: “Yup, they had Jay-Z. They even had Mos Def when he was with Urban Thermo Dynamics.”

Was the plan from the beginning for Premier to produce the album entirely?

Jeru: “100%.”

Because other than a Gang Starr album, he had never produced a full project for anyone before that.

Jeru: “Right. But what people don’t understand is that other than those Gang Starr records, The Sun Rises in the East is what actually helped define Premier as that producer. That was the most different album he had ever done, soundwise. It was a different level.

It was our personalities that was going into these records. Guru had a different personality to me – that’s why Gang Starr albums sound different. Group Home – Mel and Dap – they got a different personality. So, it was a new time. It was like being born.”

I want to get into the making of the album, but before I lose the thought – the “Come Clean” soap.

Jeru: “[Laughs.] The black soap.”

That was a genius marketing tactic, early on. Do you remember the story behind that idea?

Jeru: “Of course. I said I wanted to use the black soap, because I was into natural shit. It was ‘Come Clean,’ so we used black soap because it was supposed to get you the cleanest. I used to go to this spot Medina in Brooklyn where I used to buy my incense, black soap, and all that. We just went there and bought mad black soap. It’s funny because the Medina label was damn near the same fluorescent green as our label. So we just put our label on top of that label. It was a promotional item. Industry people really got it. That’s when I started getting into the industry side of things. [Laughs.]”

Getting back to Premier. You guys had this crazy chemistry. What do you think it was that allowed you to work so well together, being that it was your first album? Did it stem back from you being friends and being around Gang Starr for so long, or was it something beyond that?

Jeru: “That’s really it. It was us being friends and we got chemistry. And I wasn’t the type of person to accept something I didn’t like. I gave him my feedback, and he would work around that. He’s like a tailor. It’s not like one suit fits all. He tailored it around my taste.”

And he was familiar with your taste. And there was a comfortability there where you could be honest with each other.

Jeru: “Right. That’s my man. We ain’t sensitive like millennials. [Laughs.] We ain’t even think no shit like that. Like, ‘Oh my God, he might take it the wrong way.’ We used to say whatever to each other anyway. That’s your brother. It wasn’t too many of those moments, though. And like I said, I loved the process of the studio. A lot of people don’t know this, but when Premier did the Illmatic album with Nas, I was in the studio for almost every session. I was the official blunt roller. It would be me, Premier and Nas in the studio – only.”

That’s incredible.

Jeru: “I loved the whole process. I loved to watch Premier work, to learn about all the machines, and how the samplers work, and what this and that did. I was, and still am, very curious. I loved every aspect of it. That’s why when I got my deal, I went and got an MPC3000, I started collecting records, I started learning how to make beats. Because I’m creative. I like to create. And that’s what it was with me and Premier. It was just two creative minds. You put two creative minds in their own space and just let them go.

And another glue that stuck us together is that, we’re not like these cats today. We wanted to burn everybody. It wasn’t just about getting some money. You wanna kill motherfuckers. We wanted to be the best. Because we’re fans. We’re listening to everything. Today, it’s different. It’s not to say that what they’re doing is wrong. But the vibe is different. Everybody’s happy, and everybody wants to be in the same space. Before, everyone wanted to carve out their own space. And, you wanted your space to be flyer than the next man. It was a friendly competition.”

When you were in the studio, were you guys making everything on the spot?

Jeru: “It depends on the day. Some days, we’d sit in there all day – he’s making drum patterns, we’re listening to records and records and records – and nothing would happen. And then there were those days, and we’d sit down, we’d be smoking and eating and whatever, and then, boom! It comes together. I’ll write the rhyme, and go record it – and we would do it in one take, or a few takes. There was no punching in or anything like that.”

Can you remember one beat on there that you particularly reacted to like, “Oh shit, this is crazy” when you first heard it?

Jeru: “All of them. ‘Can’t Stop The Prophet,’ ‘Ain’t The Devil Happy,’ ‘Da Bichez.’ That’s why I wrote to them.”

‘Statik’ was crazy. We had been talking about how we loved how samples sound, with the static and everything. And I was like, ‘Yo son, we should do a record with just static.’ That’s how our shit would come about. The next thing I know, he come with some static looped and he just grabs the basslines. Like I said, it was all organic.”

In terms of the whole album coming together, and the balancing of songs with themes and the straight emceeing and all the beats and sequencing, was that all natural too? Because for a debut, it’s impeccably put-together.

Jeru: “I give everything a name first. Then once it has a name, you know what’s gonna go in it. I already knew the title of the album before we even started working on it. Then once I get a beat, I give it a title. Or else I don’t know what I’m writing about. I’ll just be writing random shit.

I got some old rhyme books from like ‘83, ‘84. And I’d spend hours and hours just making up titles and names of stuff. It looks like an old Kung Fu manuscript, all rolled up with a string tied around it. I got it at my mom’s crib. I peeped it, and on the cover, it’s just mad titles. Because I was always good at giving thing names. Because the name is what it is. That’s why you’re supposed to be careful what you name your child. Because a name manifests what it is.”

It’s interesting that you say that, because I did a similar interview piece with Premier for Hard To Earn about five years ago when it had its 20th anniversary. And he told me that Guru used to give him a list of song titles, and he would make the beats based off those song titles.

Jeru: “Great minds think alike. I was a part of the process with some of those names. I’d be with Guru and they’d be going through it. Guru’s my dude like that. Me and him and Dap would sit down and talk about titles and subject matters and shit like that. A lot of shit on Gang Starr records I helped name. Like for instance, Guru has a record called Jazzmatazz.”

Of course. Classic.

Jeru: “I made that up. We got into an argument because he wanted to give me $50 for the name, and Premier made him give me $500.”

Because that became a brand.

Jeru: Exactly. But it’s just – great minds. You’re attracted to people that are similar to you. And Guru knew that as well, with the names. Everything starts with the name.

Was there anything from those Sun Rises in the East sessions that didn’t make the album, or that you saved for later?

Jeru: “Nah, everything went in.”

The Sun Rises In The East comes out May ‘94. Illmatic comes out April ‘94. Hard To Earn comes out March ‘94. You’re in the sessions for both those albums. What was the benefit for you from being around those other Premier-produced classics that were being made at the same time as you were working on your debut?

Jeru: “It’s like what would one Kung Fu practitioner get from being around other Kung Fu masters? Or a great chef around other great chefs. You get a peek into their process, and it inspires you even more. Because you’re like, ‘Wow, these motherf—ers are incredible. I gotta step my game up.’

It instills in you a greater work ethic. We’re talking about Nas and Guru. They’re getting their verses in on one take. You seeing master craftsman at work. So it inspires you to be a master of your craft. You see dudes sitting down, busting out a song right there. You’re like, ‘Oh word. I gotta be on my game.’ It keeps you sharper.

And then, there’s different levels of masters. Because Nas is new. Whereas Guru was a veteran. So there’s different things you get from them. I learned my work ethic from Guru. And from Nas, I observed the enthusiasm, and the ability to seamlessly create. These are my peers that I’m working around. It’s like, if you want to be a better basketball player, you don’t play the worst players. You play Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James. You don’t play the dudes that you can beat. These were dudes who I was like, ‘I don’t know if I can beat them, but I’m gonna try my best. Then when I score, I know I’m in good company.’

Is there one beat now off Hard To Earn or Illmatic, that you saw get made or became a fan of, that you would say, “Damn, I wish I could’ve had that for The Sun Rises in the East?”

Jeru: “Everything on the Livin’ Proof album! [Laughs.] Every beat. That album!? Whooooooo! I’m actually about to call Lil’ Dap after I get off the phone with you.”

I love that answer. “2 Thousand” is one of my favorite beats of all-time.

Jeru: “‘Two thousand is mines.’ Come on. ‘Up Against The Wall.'”

Both versions.

Jeru: “That’s what I’m saying! Everything on the Livin’ Proof album, yo.”

There were other guys coming out with their debut around this time in ‘94 besides Nas. You had guys like Method Man and O.C. and Biggie. I know you and Biggie went on to exchange subliminal blows on wax, but you were cool around this time, right?

Jeru: “Biggie was my man. The subliminal blows was at me. I never made any references to Biggie on my record. That’s a total misconception. Premier will tell you. I had a little problem with Puffy. I felt he offended me. I was a fragile, young individual. But I loved Biggie. A lot of people don’t know, but the ‘Ten Crack Commandments’ – I let Biggie have that beat. I did the Hot 9 at 9 promo for Angie Martinez, and B.I.G. asked for it.”

I remember seeing a picture of Biggie wearing a Jeru shirt with your logo on it.

Jeru: “Listen, Biggie was my man. Things got misconstrued, and then we never got a chance to talk because he got killed. But I mean, I love Biggie. And Premier will tell you. Cease, Kim – those are my people. I came at Puffy. And here’s the thing you gotta remember. I was saying motherf—ers’ names. If I had a problem with you, I said your name. And then this way, you could come see me.”

Did you and Biggie have a musical relationship, where you played each other stuff?

Jeru: “He was just my man. He was like, ‘If you ever do a video for ‘Brooklyn Took It,’ I just wanna stand right there.’ We never talked the whole time of that. I told Preem, ‘Next time you go to the studio [with Biggie], holler at me so I can go.’ But I think I was out of town when it happened. And Puffy, that was something I had against him. But it was childish, and I was a child. You’re in the hood, and you have a fragile ego. And I felt like he did something that bothered me, and I put it on blast.”

I’m glad we’re talking about it. Because as a hip-hop fan, it seemed like there were some misconceptions as to what it was.

Jeru: “This is what happened. Biggie had his release party at The Palladium. And we went to The Palladium, and they turned us away. Me, Premier and Method Man. Because we didn’t have suits and shit like that. They said we wasn’t dressed right. And that pissed me off. So we got into a little altercation. But then Puffy sent security to go to the back, and he let us in and apologized. I should’ve left it like that. But I was offended, like, ‘Ah man, n—-s is fucking up hip-hop. Makin’ it all jiggy. How Preem can’t get in and he produced a track on the album. How Method Man can’t get in and he’s on the album.’

But to be fair, Puffy sent security and he let us in, from the back. We had to come in like slaves. [Laughs.] But it’s really childish, to make a whole issue out of that. He came and apologized. And as a man, I should’ve left it at that. But I was a child, and it was principle. And principle meant everything. People have all these deep theories, but it was nothing. It was about that. Now me, I’m feeling self-righteous at the time. I’m hot. I’m Jeru The Damaja, the prophet. So let me use my prophetic ability to speak about the situation.

But this is the funny shit. If you look, everything I said now 25 years later is coming to pass. Look at how the industry is – the lack of creativity, all about money, over-feminized. I was saying the truth, but my motive was a little juvenile in the way I was saying it. I could’ve expressed it in a manner that would’ve been accepted more. But, you live and learn.”

I think something you showcase well on the album is not only your ability to rap at the highest level but your intelligence as a righteous young man. Is that something you specifically set out to do with your debut?

Jeru: “My mother told me, ‘Son. It’s rare that a young black man gets a platform to say something. So, say something.’ I’m from the street. I’m still from the hood and all that, and bust my guns or whatever. So I was talking in a language the streets could relate to. But I’m always saying something. I was born in the ‘70s and came up in the ‘80s, so we’re coming out of the Black Power movement and the Civil Rights movement. I still concerned to this day with the plight of the young black man, or woman, in America. I’m concerned with humanity as a whole. We talk about police brutality and all that – it’s still happening today, 25 years later.”

That’s right, you did have that song about the police – “Invasion.”

Jeru: “‘Invasion,’ ‘The Frustrated N—a.’ And I did that for the Black Panthers soundtrack. The social issues are still around. Hip-hop at the time was a growing, budding medium. But hip-hop done changed the whole world. I live in Berlin, Germany now because of hip-hop. It’s everything. When you speak of pop music, you’re talking about hip-hop, really. Hip-hop is the most popular style of music.

But now, if you look at it today, they’re saying less. But this is the difference between me now and then. Then, I thought people were obligated to do something. Now, I know understand the only obligation is my own, to do what I gotta do. And I still feel like it’s a powerful medium, so I’ma still do what I gotta do.”

Knowing how frequently you were in sessions with Nas and Gang Starr, I find it interesting that Afu-Ra is the only guest on the album. That was just a close friend of yours, right? He wasn’t necessarily pursuing a career as an artist?

Jeru: “He wasn’t even rapping at first. I taught him how to rap. I don’t even know why Guru wasn’t on the album, to be honest. But at that time, you didn’t just make records with everybody. It was just with certain people. Now, the whole album be features. Dudes probably write one verse for every song. But back then, it wasn’t like that. It was about showing your merit. It’s my album. And Afu was just my right-hand man, that’s all. He was my sidekick.”

I like how you bounced back and forth off each other. That’s something people don’t do much anymore.

Jeru: “I got that idea because one of my favorite groups ever is EPMD. And they used to bounce back and forth. I was like, ‘Yo, I wanna do something like that.'”

And all that scientific talk, was that stuff you were just into? I know you said you had a book stand, I assume you were a big reader.

Jeru: “I’m still into all that. I’m a scientist, to this day. [Laughs.]”

I always thought that was so cool, as a kid listening to you. Like, “He’s rapping about science and mathematics, but it doesn’t sound corny.” Not everyone can pull that off.

Jeru: “I’m a nerd. I’m just a tough nerd. [Laughs.] Math, science, literature. I’m a fan of learning. When computers came out, I put computers together, all types of shit. Any type of knowledge out there, I wanna know.”

That verse from “Mental Stamina” earned you Rhyme of the Month in The Source. As a teenage hip-hop fan, that was something I was checking for every month. But was that something that you as an MC, or artists at that time, were talking about?

Jeru: “To get the Rhyme of the Month in The Source?! Come on. That was props. It meant a lot. Every accolade I got meant a lot. As an MC, that’s what you wanted. The Source was the hip-hop bible. The Source meant more than Vibe and all that. If you had Rhyme of the Month in The Source, every MC, producer, record company person – they all knew about it.”

Obviously, you’re a man who cares about every bar. But is there another verse off that album that you thought was particularly dope, that maybe you would have personally chosen to be Rhyme of the Month?

Jeru: “Every verse. I think that was a good one, though. Because it was aggressive. It was lettin’ dudes know. ‘Pugilistic linguistics, check out the mystics, we’re fantistic / You mean fantastic, f— it, you’ll get your ass kicked – ”

“Challenge my verbal gymnastics.” I love that verse. Aside from The Source, another way for artists back then to get national exposure was through music videos. You had some classics. I can still picture myself as a kid watching the “D. Original” video on Yo! MTV Raps, with you rapping on the subway platform. But the one that was particularly dope was the “Can’t Stop The Prophet” video, with the animation.

Jeru: “It was the only video of its kind like that. You see that now, but we pioneered that. No one did that before we did that. Shout out to my man Daniel Hastings and Chris Cortez. After the first two videos, I always had a hand in my videos, and wrote the treatments. So me, Daniel and Chris, we came up with a whole storyline. Chris drew all the stuff, and Daniel directed it.

And all that stuff was physical. It’s not like the animation you see today. The subway train and all that shit you see moving, that was actually a physical 3D city that they built. That train was really moving. That train station was cutouts, all set up. There was some animation. But you gotta remember, at that time it cost so much money to do that. So we had to figure out a way to stay within budget, and still make it creative and ill.

Actually, this year I’m coming out with the ‘Can’t Stop The Prophet’ graphic novel. And I’m working with Daniel and Chris, the original creators. I got a lot of stuff coming out this year that I’m excited about.”

Daniel Hastings also did the art for the album cover. The Twin Towers are on fire on the cover.

Jeru: “That came from us sitting down and talking about the idea. So it was like, ‘Imagine if the sun was that close to the Earth. Because I’m the sun. So what would happen? It would cause all types of natural disasters – the Statue of Liberty is in the water, the Twin Towers is on fire. It’s also because I’m The Damaja – I’m bringing that wrath, that destruction, that lyrical fire.”

And then, of course, 9/11 happens.

Jeru: “I’m not gonna sit up here and say that I’m a prophet or something. It just so happens the things that I say are prophetic. I spoke about the situations happening in hip-hop, and now everyone’s complaining about the same things. Even Puffy is getting on there saying, ‘It’s too much.’ That’s 25 years later. So what does that tell you? I guess everybody got a gift in life. I just got vision – and I’m not saying that in a supernatural way.”

You mention “bringing that wrath,” which made me think of your sophomore album Wrath of the Math. And it’s also produced entirely by DJ Premier. How are the two albums different? And do you have a favorite of the two?

Jeru: “The Sun Rises in the East is my baby. And there will never be another one. It’s the purest album that I ever made, for that time period, until I make another with that same pure energy. Wrath of the Math, it was the sequel, but I like The Sun Rises in the East better. It was more creative. I had more of an agenda on Wrath of the Math. It was organic, but I still had an agenda.”

Decades later, when you think back about The Sun Rises in the East, how does it make you feel?

Jeru: “The genuine feeling that I have is that I’m truly blessed and thankful that I was able to create something that could sustain not only myself but different people over the years. I have people who write me and tell me how the album has helped them and changed their life. So I just feel really blessed, that I was able to put something in the universe that will be there forever. And it shows me how far I’ve grown. I’m grateful.

Also, in thinking back 25 years, I want to make sure I thank Guru – RIP – for giving me that chance. And also DJ Premier for being a part of the whole process, and everything. It’s just graciousness all around, 360 degrees.”

Listen to the expanded edition Jeru The Damaja’s The Sun Rises in the East now.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2019.

Y. Watts

March 28, 2023 at 5:50 am

Super dope read. First time I’ve seen Jeru talk about the beef with Puff & Big, and tell the entire story and give Puff props.