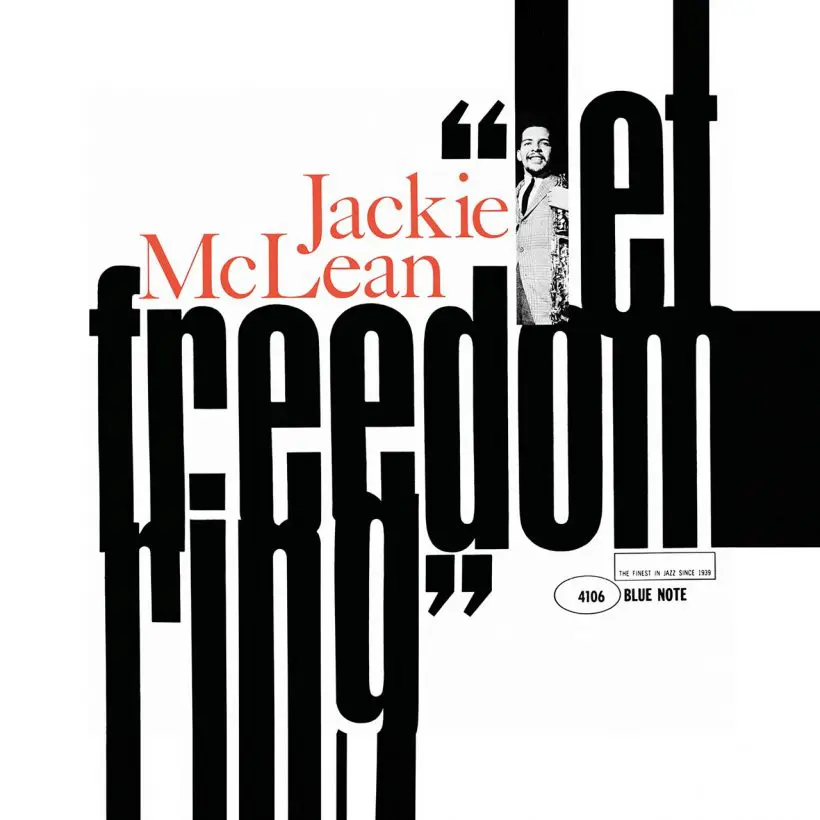

‘Let Freedom Ring’: How Jackie McLean Began To Break Free

The story behind the alto saxophonist’s 1962 manifesto for musical liberation.

Anyone who is familiar with Jackie McLean’s classic Blue Note album Let Freedom Ring will know that the alto saxophonist had one of the most distinctive sounds in jazz. His instrument’s intonation was always intentionally slightly sharp, which resulted in an acerbic tone that gave his music a cutting edge. It wasn’t to everyone’s taste, of course, and for some listeners, it was a sound as jarring as fingernails clawing a chalkboard. But for McLean, who once proudly declared, “I’m a sugar-free saxophonist,” his divisive sound mirrored his personal circumstances: “My life has been sweet and sour, bittersweet, and I’m interpreting my experience.”

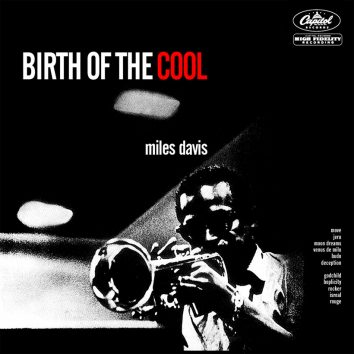

On the face of it, Let Freedom Ring appeared to be just another record date in a long line of sessions that the young alto saxophonist had recorded for Blue Note after joining the company in 1959. Before that, he had recorded several LPs for Prestige in the wake of his recording debut as a 20-year-old wunderkind on Miles Davis’ 1951 album Dig. Influenced by Davis along with Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, and Thelonious Monk, McLean gradually developed his own sound and became a committed disciple of hard bop, an earthy, blues and gospel-stained offshoot of bebop that had become jazz’s hottest currency in the 1950s. But like his early mentor, Miles Davis, McLean was a restlessly curious musician who grew averse to repeating himself. You can hear this loud and clear in Let Freedom Ring, a landmark album that marked a decisive inflection point in the saxophonist’s career.

Listen to Jackie McLean’s Let Freedom Ring now.

Like many jazz musicians working in the late 50s and early 60s, McLean had been deeply affected by the revolutionary approach of Ornette Coleman, who had thrown the musical equivalent of a hand grenade into the jazz world with his explosive 1959 album The Shape Of Jazz To Come. Jettisoning orthodox concepts of melody, harmony, structure, and rhythm, Coleman divided the jazz community. Some, like McLean, were hugely excited. McLean saw possible solutions to musical issues that he was grappling with around the same time.

Indeed, in his liner notes to Let Freedom Ring, McLean confesses that “getting away from the conventional and much-overused chord changes was my personal dilemma.” In other words, he was beginning to find that hard bop had become a musical cul-de-sac and was both restricting his creativity and taxing his imagination. But Coleman’s innovations offered a way out. “(He) has made me stop and think,” wrote McLean in Let Freedom Ring’s liner notes. “He has stood up under much criticism, yet he never gives up his cause, freedom of expression.”

Click to load video

Given his feelings at the time, it was no surprise to see McLean recruit Ornette Coleman’s drummer Billy Higgins to play at the recording session taped at Rudy Van Gelder’s famous studio in New Jersey. “I sure dig the groove Billy gets,” McLean said of the 26-year-old Los Angeles sticks man, who had appeared on The Shape Of Jazz To Come and several of the contentious saxophonist’s other groundbreaking late 50s/early 60s records. On bass, McLean brought in 21-year-old Herbie Lewis, who had played on several sessions by soul-jazz pianist Les McCann, and occupying the piano stool was 29-year-old Walter Davis Jr, who had cut his teeth with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Lewis and Bishop, with their receptive soul jazz and hard bop backgrounds, hardly seemed revolutionaries or musicians intent on pushing the jazz envelope but with their presence, McLean seemed to find a sense of musical balance – between hard bop and ultra-modernism – that shaped the unique character of Let Freedom Ring.

In fact, the album bore little resemblance to the sonic extremism of Ornette Coleman. By turns haunting and hard-swinging, “Melody for Melonae” – written for and dedicated to McLean’s then six-year-old daughter, Melonae – used the scale-based modal structures that Miles Davis helped pioneer on Kind Of Blue while “I’ll Keep Loving You,” was a cover of a Bud Powell ballad transformed by McLean’s eerie, high-pitched squeals. And the language of the blues was prominent in both “Rene,” named after McLean’s son, and “Omega,” written for his mother, Alpha Omega McLean.

Click to load video

Sonically, the music walked a tightrope between the conventional and unorthodox; a quality that would be further reflected in McLean’s work as the 1960s unfurled. Let Freedom Ring, however, is where it all started. Without Freedom’s emancipation from the jaded vocabulary of bebop, there would be no One Step Beyond and Destination…Out!, albums which firmly placed McLean firmly in the vanguard of improvised avant-garde music.