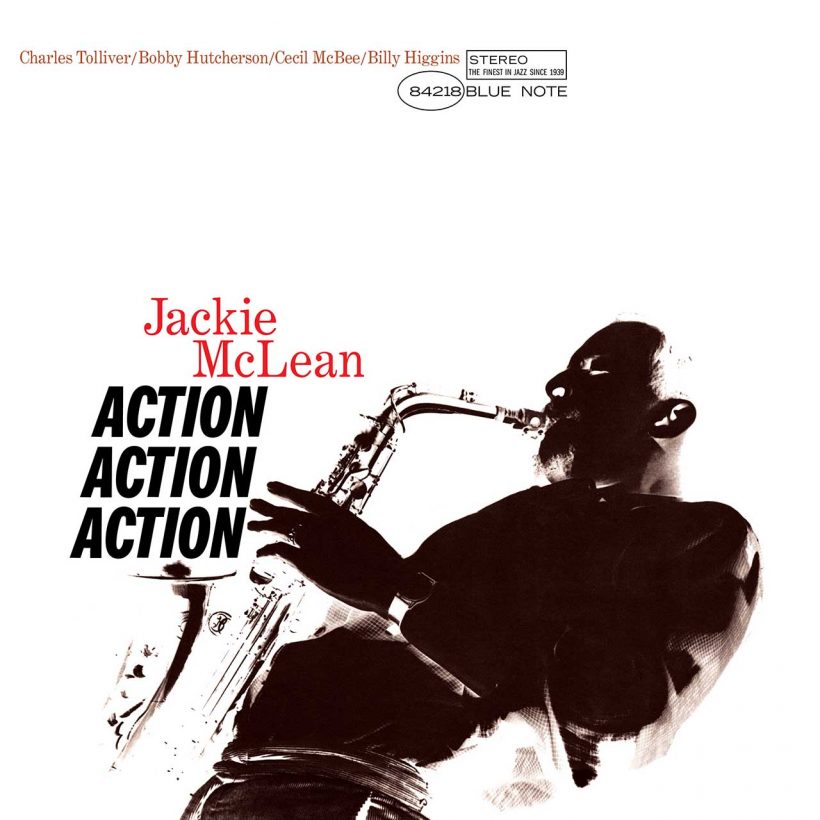

‘Action’: Jackie McLean’s Envelope Pushing Jazz Classic

The jazz saxophonist’s 1967 album bridged the space between hard bop and progressive music.

A disciple of bebop architect Charlie Parker, wunderkind alto saxophonist Jackie McLean was just twenty when he made his recording debut on Miles Davis’ 1951 album Dig. Born John Lenwood McLean in Harlem, McLean quickly lived up to his early promise. Following his 1954 debut LP Introducing…Jackie McLean: The New Tradition, he recorded a bunch of commendable hard bop-style solo albums for Prestige. In 1959, after a stint in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, his career gathered momentum when he joined Blue Note Records, widely considered jazz’s leading independent label. McLean’s musical development at Blue Note from 1962 onwards was astonishing, releasing a series of progressive albums that broke new ground while anchored, albeit loosely at times, to the jazz tradition. Of the 21 albums he recorded at Blue Note between 1959 and 1967, Action was one of his best.

No other saxophonist sounded like McLean. Steeped in blues and bebop, his horn possessed a tart, astringent tone, a characteristic that always gave his music a disquieting flavor. It wasn’t until his eighth Blue Note album, 1962’s Let Freedom Ring, that McLean showed how the “New Thing” – spearheaded by Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane – was beginning to impact his approach to jazz.

Listen to Jackie McLean’s Action now.

After Let Freedom Ring, McLean grew more audacious with a succession of envelope-pushing LPs in the next two years, including One Step Beyond, Destination … Out!, and It’s Time. The latter album introduced Charles Tolliver, a 24-year-old trumpeter who quit his job as a pharmacist to pursue jazz professionally. McLean was so impressed by his new protege that he featured two Tolliver tunes on his next album, Action, recorded in September 1964.

Besides Tolliver, Action featured musicians McLean was familiar with: Vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson – renowned for his ability to play straight-ahead jazz and more experimental music – bassist Cecil McBee, and drummer Billy Higgins. The album was cut at Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey, Blue Note’s preferred recording space run by pioneering sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder. In the producer’s chair was the label’s co-founder, Alfred Lion. “We would rehearse for a couple of days during which he would time everybody with a stopwatch and decide how many solos there’d be,” recalled Tolliver in 2020. “Then we’d go off to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio and the recording would be done inside of three hours.”

An almost ferocious sense of urgency propelled Action’s opening title cut, whose intro featured eerie harmonized horn motifs over martial drum rolls before exploding into a frantic groove driven by McBee’s galloping bass. “The way the melody moves is the sound of something happening,” said McLean, explaining the track to writer Nat Hentoff. “Once the solo improvisations start, there are no chord changes and no scales to follow.”

After “Action’s” relentless propulsion, “Plight” is slower and more mysterious, with Hutcherson’s glinting vibes adding an otherworldly quality. Tolliver, whose trumpet lines shimmer with a translucent beauty, wrote the track along with “Wrong Handle,” a carefully structured melancholic ballad with lyrical horn solos. In sharp contrast, the jazz standard “I Hear A Rhapsody” sees McLean fall back into a hard-bop comfort zone. “I never want to go ‘outside’ for too long a time without coming back ‘inside’ again,” he explained to writer Nat Hentoff. Action’s curtain closer was a driving bop-tinged original which McLean enigmatically described as “a blues without being a blues.”

Balancing his more progressive inclinations with deep bebop roots, Jackie McLean demonstrated with Action a dual musical personality that allowed him to probe and explore jazz’s outer limits without abandoning the music’s traditions. It proved one of the most satisfying and purposeful recordings of his career.