Inca Records: A History Of The Puerto Rican Salsa Label

The launching pad for luminaries such as Tommy Olivencia and Willie Rosario, Inca Records brought a distinctly Puerto Rican sound to salsa.

When the Dominican music virtuoso Johnny Pacheco and the Brooklyn-born lawyer Jerry Masucci teamed up to form the inimitable salsa label Fania Records, the stars seemed to align. The duo captured the salsa phenomenon before it even had a name, and their efforts would help shoot the genre into the global spotlight. But Fania’s success wasn’t just a matter of fate. Pacheco and Masucci had two important qualities: sharp business acumen and an undeniable eye for talent. The combination explains, in part, why they began scooping up New York City labels such as Tico Records, Alegre Records, and Cotique Records in the early 1970s – acquisitions that shrunk their competition and expanded an already impressive roster of artists. Around this same time, they made one especially keen purchase: They added Inca Records in Puerto Rico to the Fania family.

Surprisingly little information exists about the origins of Inca Records, which started in 1965 through the efforts of Jorge Valdés, a Cuban transplant living in Puerto Rico. While his name might not be well known in the salsa pantheon, the acts his label convened became some of the most famous on the island. Inca Records was a launching pad for luminaries such as Tommy Olivencia, Willie Rosario, and La Sonora Ponceña, the beloved orchestra that Fania All-Star Papo Lucca began playing with at the age of five.

Inca Records released music as a Fania subsidiary until 1995, focusing its last years on a parade of Sonora Ponceña records. The label has slipped so tightly into the DNA of Fania that it often doesn’t get celebrated on its own. But its history deserves recognition for its distinctly Puerto Rican sound and some unforgettable talents.

Listen to the best of Inca Records on Apple Music and Spotify, and scroll down for our history of the label.

The foundations

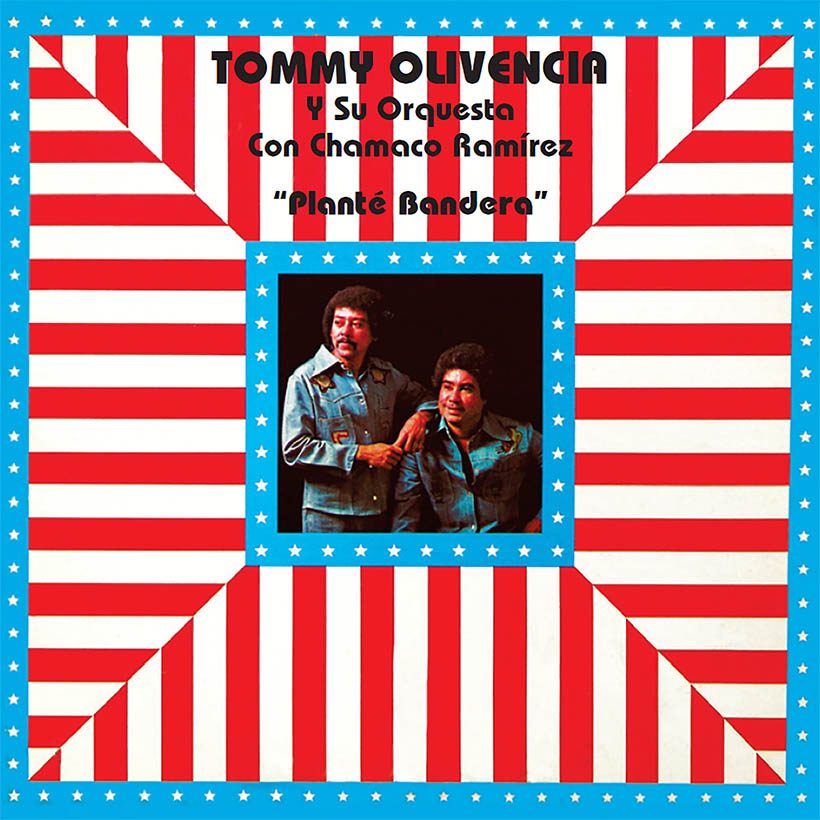

Tommy Olivencia was destined for music. The musician picked up the trumpet when he was a teenager and eventually formed the orchestra Tommy Olivencia y La Primerísima Orquesta de Puerto Rico – the first act signed by Inca. The group’s 1965 debut album, La Nueva Sensacion Musical De Puerto Rico, captured what a striking sensation they’d become, and included an early version of the salsa classic “Trucutu.” The recording featured Olivencia’s secret weapon, the sonero Chamaco Ramírez, who joined Olivencia when he was barely 16. Ramírez leads the song with his instantly recognizable, slightly nasal tenor, but his claim to the track is even greater: He wrote it, proving his skill as a composer.

The calypso-tinged anthem “Fire Fire In The Wire Wire,” released later in 1967, featured Ramírez singing alongside the silky crooner Paquito Guzmán, their two voices melding together over an ecstatic tangle of trumpets and rapid-fire percussion. Guzmán often sang for Olivencia and filled in for Ramírez; he launched several solo projects on Inca Records, including a 1972 self-titled debut and 1975’s Escucha Mi Canción. His style as a smooth balladeer helped herald the romantic chapter of salsa that found commercial success in the early 80s and 90s.

Meanwhile, by 1960, a Puerto Rican bandleader and multi-instrumentalist named Willie Rosario had already bounced around a couple of different labels. He’d had a stint with Alegre Records, performing on a few recordings by the Alegre All-Stars, and later made a boogaloo album on Atlantic Records. Because he’d moved to New York as a young man, Rosario was a fixture on the salsa scene and he’d made friends among musicians such as Bobby Valentín, who pointed him toward Inca Records. After signing to the label, Rosario released 1969’s El Bravo De Siempre, with a titular track that had success back on the island.

Although Olivencia and Rosario became venerated figures in salsa, Sonora Ponceña might be the contribution from Inca Records that had the biggest impact. The band formed in the mid-1950s through the efforts of Enrique “Quique” Lucca Caraballo, the original band director. His son, a child piano prodigy called Papo Lucca, eventually took the reins as director. But first, he played with the band for years, including as a 21-year-old on Sonora Ponceña’s first Inca Records release, Hacheros Pa’ Un Palo.

The hidden gems

Chamaco Ramírez recorded his only solo album, titled Alive And Kicking, after a period struggling with addiction and incarceration. His voice, a combination of force and vulnerability, shines on the sprightly “Kikiriki” as well as on the bolero-style “Cuando Manda El Corazon.” The record feels like it could have been the start of an exciting new career turn for Ramírez, but sadly he died less than four years after its release.

He’s remembered fondly among old-school salseros today. However, his memory is somewhat underappreciated in the mainstream world. The same goes for Leyo Peña and Monguito Santamaría, both who have been all but forgotten in music history. Peña was a bandleader who loved variety. Following his 1967 debut Feliz Yo Viviré, Peña’s group offered the salsa canon 1972’s Que Traigan El Son Cubano, which combined guaguancó, Cuban son, and cha-cha – “Guaguanco Borincano” is one example of how easily he melded these sounds. Monguito Santamaría was the son of the famed percussionist Mongo Santamaría, but his instrument was the piano. He showed off the breadth of his skill on En Una Nota! Songs such as “Devuélveme la Voz” feature sublime improvisations.

The Fania effect

Inca Records released one last album – Johnny Olivo’s Que Te Vas… – before it joined Fania. Masucci turned to Ray Barretto and Larry Harlow to help with production for the label’s newly acquired Puerto Rican artists. In liner notes written by Robbie Busch for Fania, Harlow remembered producing Sonora Ponceña’s third record, Algo de Locura. “That was one of my first productions,” he said, “And I was kind of assigned that by Jerry Masucci.” Although he didn’t know much about the band, he was able to bring out their bold, tight artistry. “They were a simple, easy band to produce, because it was just trumpets,” Harlow recalled. “They were a good band, very well-rehearsed, because they played every day in Puerto Rico and they had been playing those songs for a while before they went into the studio.” The fluidity of their partnership can be heard in songs such as “Acere Ko (Rumbon),” the first cut from the album.

Barretto, a relentless experimentalist, would also influence Inca’s direction. He looked after sessions with bands such as Orquesta Nater, which despite having one record on the label made an impression with the catchy “Vamos A Soñar.” Barretto also had an indirect hand in the formation of Típica 73: The band was made up of his former players, many of whom had an affinity for plush charanga rhythms. Típica 73’s lineup changed over the years, but its inclusion of both Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians was reflective of the ties between the two islands and how they informed the other’s salsa’s tradition. Their self-titled release on Inca Records was overseen by Johnny Pacheco himself and resulted in “Acere Bonco,” notable for its breakneck pace.

The classics

Inca Records has countless moments of sonic ingenuity. Many songs remain timeless, and contemporary artists have imbued several with new life. The reggaeton artist Tego Calderón borrowed the enthusiastic patriotism of Tommy Olivencia y La Primerísima Orquesta’s “Planté Bandera” for his rendition of the same name.

Sonora Ponceña is still active today and a version of their song “Jubileo” appears on records celebrating many of their anniversaries. Critics have called Sonora Ponceña’s “Fuego En El 23,” originally written by Arsenio Rodríguez, one of the greatest songs in salsa.