Ice-T’s ‘Home Invasion’ Still Resonates As A Curious Document Of Protest

The rapper’s fifth album feels more relevant than ever.

At the very end of his fourth album, 1991’s O.G. Original Gangster, Ice-T offered a warning about the coming months: “This album was completed on January 15th, 1991. By now the war’s probably started, and a whole bunch of people have probably died out there in the desert over some bullshit. There’s a war going on right now in my neighborhood, but I can’t really determine which one’s worse.”

He couldn’t have been more dead-on with the timing. The day after the album wrapped, January 16th, the United States and its coalition partners began a bombing campaign of historic proportions, dropping nearly 90,000 tons – be honest: the number is so big you can’t even begin to wrap your brain around it – of explosives on Iraq. Officially, Operation Desert Storm lasted from the 17th through the end of February. All told, the Gulf War claimed the lives of 292 coalition soldiers, as many as 50,000 Iraqi soldiers, and thousands of civilians in Iraq and Kuwait. Hundreds of Kuwaiti men and women were found in mass graves in Iraq. For some reason, veterans of the war had children with abnormal rates of a certain heart valve defect.

Ice-T was uniquely qualified to compare the Gulf to his own blocks. After the New Jersey native lost both of his parents – each to a heart attack, several years apart – he moved to Southern California, and eventually to South Central Los Angeles. After his daughter’s birth, he joined the Army, where he served for four years with the 25th Infantry Division. It was in the Army that he first developed an interest in hip-hop. (Ice – he was still Tracy Marrow at this point – was also in the Army when he was introduced, in Hawaii, to a pimp who presumably lent some detail to Ice’s early rhymes.) So as the Clinton years began, and as cultural conservatives waged wars against black artists in the press and at absurd CD-crushing demonstrations, Ice-T took it upon himself to be a lightning rod.

Ice’s fifth album, Home Invasion, is a curious document of protest, one that was overshadowed in its time by the circumstances surrounding its release. But to properly understand it, you need to loop back to Ice-T’s earlier work to find where the threads of these arguments – that rap would never be properly understood by the American establishment – began.

Put simply, “6 in the Mornin’” is a masterpiece. Of the songs that followed in the immediate wake of Scholly D’s “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean?),” “6” had the most legs on the West Coast, and had the added benefit of introducing, in Ice, a rapper whose on-record persona was already fleshed out and endlessly colorful. Listen to it today: the peculiar shape to the vignettes, the wit, the worldview could all cut through today’s din, too. It’s a remarkable song, and one that helped codify gangsta rap into a subgenre that would soon barrel into the American mainstream.

Click to load video

Beyond that song, Ice’s debut album, Rhyme Pays, was largely a party record. But there’s groundwork being laid that would become important later. First, the record opens with Ice drawing an explicit line between art and street life – not as a question of an artist’s moral culpability, but as something that can occupy the time of a young person. More pointedly, Rhyme Pays ends with “Squeeze the Trigger,” a furious rebuke of those who call rap violent but uphold the police complex. (It also takes aim at the White House: “Ronald Reagan sends guns where they don’t belong.”)

Power, his classic from 1988, finds Ice more composed. His vocals are more assured, more direct. So is his writing. From “Radio Suckers”: “I thought you said this country was free?” Beginning with Power, there’s a shift in Ice’s writing; he moves away from primarily documenting South Central to grappling above all else with how hip-hop is perceived in America. “I’m Your Pusher,” the album’s instant-classic lead single, addresses this directly, likening Ice’s music to packaged narcotics. Power stayed on the Billboard 200 for 33 weeks. When it came time to do album number three, Ice doubled down on this approach: that record would be called The Iceberg/Freedom of Speech…Just Watch What You Say! It was informed by Ice’s experiences being censored on tour, and by the Tipper Gores of the world, and was punctuated by barbs like “I’m the one your parents hate.”

Nothing could have prepared him, though, for the avalanche of criticism that was coming. Just over six weeks after Ice recorded that warning about the coming wars, a man named Rodney King was brutally beaten by LAPD officers following a traffic stop. A year later, after three officers were acquitted – despite widely-seen video of the beating – riots erupted in Los Angeles. It was in the midst of this political climate that Ice-T released, with his metal band Body Count, a song called “Cop Killer.” Both George Bush and Dan Quayle – who would also take aim at 2Pac – decried the song, and pressured Warner Bros. to pull the release.

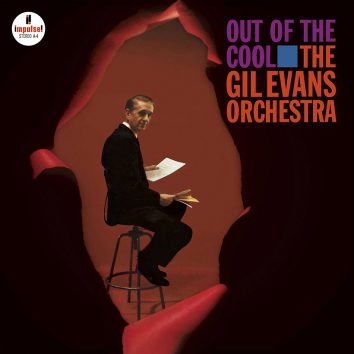

It was in this context that Ice-T wrote and recorded Home Invasion. The title track makes its metaphor just as clear as that of “I’m Your Pusher”: Ice is kicking in the door and headed straight for your children’s ears. This is mirrored on the album’s cover: a white teenager with African medallions, Ice Cube and Public Enemy tapes, and books by Iceberg Slim and Malcolm X.

Click to load video

That cover was initially a point of contention. Home Invasion was supposed to be released in November of 1992 – just days after the chaotic election that kicked George Bush out of office. Warner was under considerable pressure at the time (both from politicians and its own executives), and the album was delayed; a nixing of the cover art and a name change, to The Black Album, were floated. Dissatisfied that his work was under the same censorious thumb it was written to critique, he negotiated a release that would allow the album to be distributed, in its original form, by Priority.

Home Invasion is a relentlessly kinetic record, bright and in constant motion. Songs like “Race War” – where Ice shows solidarity with not only non-white Americans, but with marginalized peoples in Australia and beyond – mesh their pointed politics with quick-paced, upbeat production. After settling into a comfortable pocket on O.G., Ice here sounds animated and re-energized; see his tongue-in-cheek turn on “99 Problems,” which in 2003 Chris Rock would recommend to Jay-Z for a bit of an update.

But even with the minor victories – the Priority deal, his continued stardom – Ice-T kept his eye on the real fight. Tucked near the end of the album is a song called “Message to the Soldier,” where he relays what he’s learned about wars of any kind. The enemies are American politicians: the ones who orchestrated the crack epidemic, the ones who made sure black leaders like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. never saw middle age. Rap, Ice posits, is terrifying to the white establishment precisely because it embodies the voices of resistance that the government had worked for centuries to tamp down.

Click to load video

Stream Ice-T’s entire discography here.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in 2018.