‘Home Cookin”: Jimmy Smith’s Soul Jazz Platter

The sonic equivalent of grits, greens, and gravy, the album confirmed the organist as a soul jazz master chef.

Jimmy Smith‘s ascent to the top of the jazz organ tree was spectacular and meteoric. In 1955, few who followed jazz knew who he was but a year later, after producer Alfred Lion, who was stunned by Smith in concert, had signed him to Blue Note Records, the 30-year-old Hammond B3 virtuoso’s name was on every modern jazz fans’ lips. With Blue Note issuing five LPs under Smith’s name in quick succession during 1956 alone, it was hard to escape the phenomenon that the mustachioed organ grinder from Norristown, Pennsylvania had rapidly become.

Blue Note knew they had a unique talent on their hands and, understandably, wanted to fully exploit his potential. But unlike Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nicholls, two singular keyboardists they’d previously signed but whose records didn’t sell well, Smith possessed huge commercial appeal and his records – infused with blues and gospel elements – were quickly devoured, mainly by a hungry African American audience.

Order Jimmy Smith’s Home Cookin’ on vinyl here.

Smith’s rise to fame continued unabated in 1957, when he released an astonishing seven LPs in a frenetic flurry of recording activity. Those trying to keep up with his prolific output would have breathed a bit easier in 1958 when the organist’s productivity began to slow down – but only a little; he still released three LPs that year, including the classic live album Groovin’ At Smalls’ Paradise. By the time he recorded Home Cookin’ in the summer of 1959, Blue Note had cut back on the number of his releases, perhaps wary that they were saturating the market. But at that point, Smith didn’t need to prove anything – he was a bonafide star whose infectious soul-jazz records were hands-down the best selling LPs in Blue Note’s catalogue.

The group and the recording

His sixteenth LP in just three years, Home Cookin’ followed in the wake of The Sermon!, released earlier in 1959. Only the Detroit guitarist, the exceptionally talented Kenny Burrell – who also had a Blue Note contract – survived from that session. Joining him were saxophonist Percy France – a freelance tenor player from Manhattan whose experience included playing with organist Bill Doggett in the first half of the 50s – along with Smith’s regular drummer, Donald Bailey. There was no bass player on the session, of course, as Smith played the music’s bass notes on his Hammond organ’s foot pedals.

Most Blue Note albums were cut in a single three-hour session but Home Cookin’ was a rare exception; a blend of two studio dates, from May and June 1959. All seven tracks were laid down at producer Alfred Lion’s favorite recording location, Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey; a state-of-the-art facility owned and run by the legendary audio engineer, Rudy Van Gelder, who played a key role in giving Blue Note Records its distinctive sound. (He was also regarded as the first man to bring proper audio expertise to jazz recording sessions and make musical instruments sound life-like).

For those familiar with Smith’s previous studio recordings, what’s striking about Home Cookin’ is that it’s a much more considered, laidback record, favoring simmering grooves over the organist’s customary dazzling keyboard pyrotechnics. The opening cut, a succulent soul-jazz take on Ma Rainey‘s “See See Rider,” is defined by organ licks that are so greasy, you can almost hear the fat dripping. It sets the tone for the rest of the album; though often performed as an upbeat blues shuffle by other performers, Smith slows the song down to a languorous tempo, allowing space and time for all the soloists to shine.

Elsewhere, Smith and Burrell each contribute a couple of songs alongside two notable covers; Ray Charles’ 1955 R&B hit “I Got A Woman” and organist Jimmy McGriff’s “Motorin’ Along,” which are both superbly reworked with a church revival feeling.

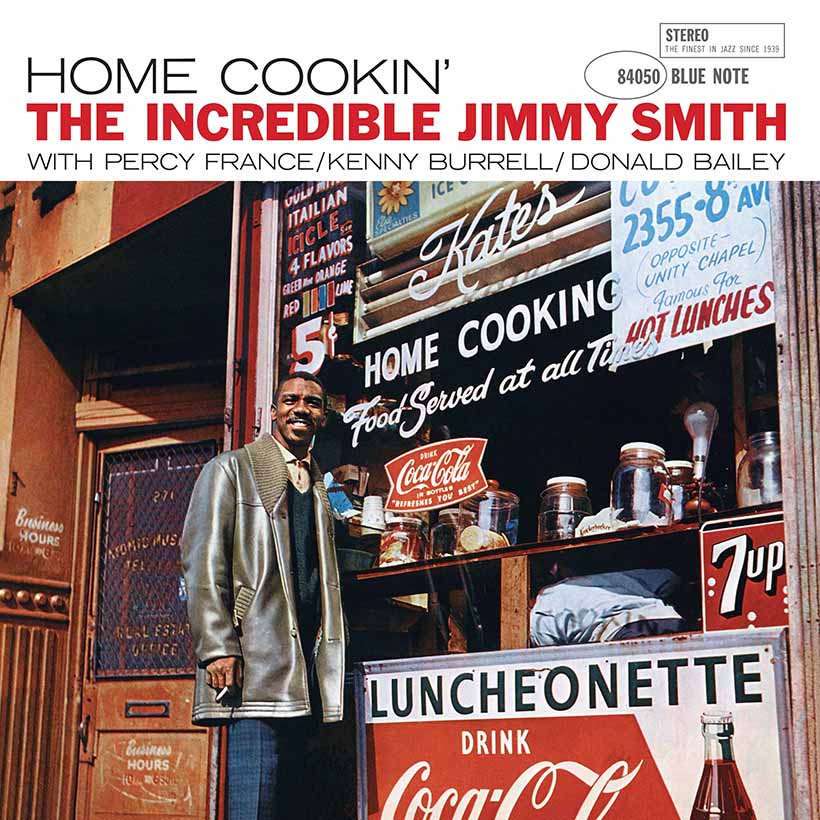

The album cover

Home Cookin’‘s eye-catching front cover is also worth a mention. By 1960, when the album was released, Blue Note’s LPs had become renowned for their stylized artwork, juxtaposing eye-catching typography with cropped black and white photos of the musicians. Up to that point, the label rarely used full-color shots of its artists, which is why Francis Wolff‘s vivid photo of Smith captured outside a Harlem soul food diner called Kate’s Home Cooking is so distinctive. The decision to photograph Smith there was not an arbitrary one – according to the album’s liner note writer Ira Gitler, Smith chose to dedicate the LP to the diner’s proprietor, Kate O. Bishop, whose establishment was just a stone’s throw from the stage door of the famed Apollo Theater. (Apparently, it was a magnet for musicians and performers who would often congregate there after shows).

The legacy of Jimmy Smith’s Home Cookin’

Home Cookin’ showed Smith maturing as an artist; toning down the flash solos he had built his fame on and instead, ramping up his music’s sense of soulful expression. Significantly, it was released at a time when jazz was beginning to experience an existential crisis. Ornette Coleman’s free jazz manifesto The Shape Of Jazz To Come had just come out and was sending seismic shock waves through the jazz world, causing the scene to splinter into factions. But while some jazz musicians were creating music that was overtly cerebral, Smith wanted to keep his music grounded and make it accessible for audiences who just wanted to have a good time; and with Home Cookin’, he skilfully combined blues and gospel ingredients with a soupcon of hard bop to create a delicious soul-jazz platter that still “tastes” good today.