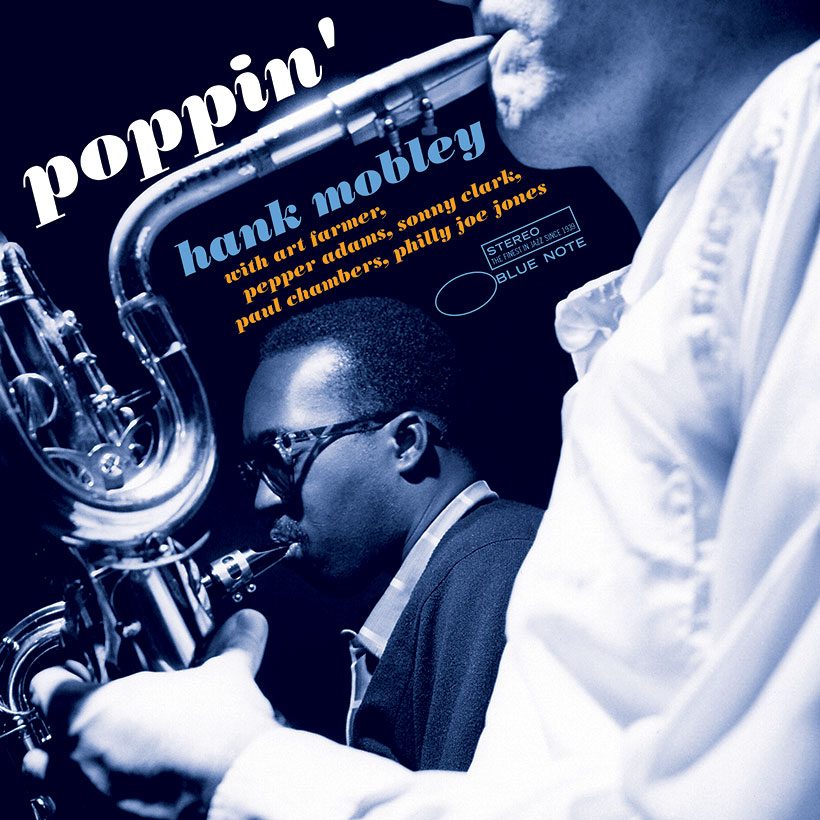

‘Poppin’’: Overlooked Hank Mobley Album Still Sounds Fresh Out The Box

Recorded in 1957 but not released for another 23 years, Hank Mobley’s ‘Poppin’’ is an exemplary slice of hard bop that deserves a far wider audience.

When the eminent jazz critic Leonard Feather described Hank Mobley (1930-1986) as “the middleweight champion of the tenor saxophone,” it was intended as a compliment. He aimed to differentiate the Georgia-born saxophonist’s mellower, softer sound from harder-hitting heavyweights such as John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. But for those who came to appreciate Mobley’s unique voice as a hard bop-era tenor player, it seemed as if Feather’s words damned the saxophonist with faint praise. Indeed, the critic’s boxing analogy stuck and became something of a curse. After that, Mobley was typecast, perennially labeled a second-tier musician, despite the evidence of Blue Note albums like 1960’s Soul Station (his finest moment on record) and the earlier and more obscure Poppin’, which deserves a far wider audience than it has.

Listen to Poppin’ on Apple Music and Spotify.

A leading exponent of hard bop

Mobley was 27 when he went into Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack studio on Sunday, October 20, 1957, to record what became Poppin’. By then the tenor saxophonist, who was a former Jazz Messenger, already had six albums under his belt for Alfred Lion’s Blue Note label. He had also established himself as one of the leading exponents of hard bop, a style that was less cerebral than bebop and drew heavily on blues and gospel elements. Lion recorded the saxophonist – whose sound, compositional skill, and ability to swing he admired – at almost every opportunity. That inevitably meant that some of his sessions were left on the shelf, but Mobley wasn’t alone in that respect. A great many Blue Note recording artists – including Grant Green, Stanley Turrentine, and Jimmy Smith – suffered the same fate.

So, Poppin’ – like Mobley’s previous session, Curtain Call, recorded a few months earlier – ended up being consigned to the vaults. Though we’ll never know why Blue Note shelved it, it’s an excellent album that showcases Mobley in a sextet setting alongside a stellar line-up of sidemen: trumpeter Art Farmer, baritone sax specialist Pepper Adams, pianist Sonny Clark, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones (the latter two both seconded from the then high-flying Miles Davis Sextet).

Spectacular results

Poppin’’s opening title song is the first of four Mobley originals. The horns combine to play the main theme over a lively, swinging groove before the soloists have space to shine. Sonny Clark is first out of the blocks, delivering an agile piece of right-hand piano work. Pepper Adams follows; his virile, baritone sax has a husky, resonant tone but is also very athletic. Then comes Art Farmer, whose horn playing, with its bright timbre, is distinguished by a sophisticated eloquence. Last to solo is Mobley, whose tenor saxophone, with its light but slightly rotund sound, flows effortlessly over Chambers’ and Jones’ driving groove. The latter also shows off his drum skills with a few choice breaks before the three horns lock in for a final statement of the snaking opening theme.

Mobley rarely played jazz standards, but when he did the results were spectacular. His rendition of Jimmy Van Heusen’s and Eddie DeLange’s popular 1939 tune “Darn That Dream” is particularly lovely: Mobley’s tone is mellow, plump, husky, and full of warm emotion on both the song’s first and last solos. In between, Farmer uses a muted trumpet on his solo, which imbues the music with a languorous, late-night feeling. Adams also succumbs to the song’s deliciously laidback mood, which is enhanced by Clark’s delicate piano runs and some subtle accompaniment by Chambers and Jones. Mobley’s closing unaccompanied cadenza is perfection itself.

Fuelled by Chambers’ and Jones’ propulsive rhythms, the toe-tapping “Gettin’ Into Something” picks up the pace. Clark plays a twisting bluesy run before teeing up the tune’s harmonized theme, stated by the three horns. Mobley takes the first solo. Inspired and flowing improvisations from Farmer (this time using an open trumpet), Adams and Clark follow him before the opening theme’s final return.

An opportunity to shine anew

“Tune Up,” a cracking version of a Miles Davis tune from 1956, keeps up the high tempo but is lighter and airier. Chambers’ speed-walking bass and Jones’ fizzing drums drive the rhythm section, over which the horns enunciate the smooth contours of the song’s main melody. Solos come from Farmer, Adams, Clark, Mobley, and Chambers (who bows his bass). Mobley picks up the baton again for a while until Philly Joe Jones delivers an impressive drum solo before cueing in the rest of the band to reprise the “head” theme.

Just as good – if not a shade better – is the Mobley-penned “East Of Brooklyn,” an archetypal hard bop swinger. The horn-played main theme rides on a groove that alternates between percussive, Latin-style syncopations and a straightahead swing style. Mobley, followed by Farmer, Adams, Clark, and Chambers, are all dependable as soloists, balancing technical expertise with emotional depth.

The Tone Poet Audiophile Vinyl Reissue Series edition of Poppin’ is out now.

Nikolai Grut

October 20, 2022 at 11:54 pm

Will we forever hear this myth about Leonard Feather qualifying Hank Mobley as a middleweight champion? The context was that Stan Getz in the same breath was qualified as the ‘lightweight champion of tenor saxophone’ and no one has complained about Getz being ‘underrated’. If you don’t like Mobley, power to you. That doesn’t take away from Mobley’s artistic qualities. Mobley got caught doing heroin and did several lengthy jail sentences. In 1962 rock had already deposed jazz as a commercial genre. One reason Coltrane became a household name and Mobley didn’t is Columbia’s marketing arm and that Coltrane died but Mobley stayed alive.