Motown And Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have A Dream’ Speech

How the legendary soul imprint worked to make some of Martin Luther King Jr.’s most celebrated and inspiring speeches available on record.

It was perhaps inevitable that The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Motown Records would work together. As the premier figure in the Civil Rights movement of the 60s, Dr. King’s campaign for equality, justice, and liberation was exemplified in some ways by America’s No. 1 black-owned record label. Motown, an enterprise that primarily signed African-American artists, was well aware of Dr. King’s campaigning theology, even when the white teenage record buyers the company courted may not have been ready to embrace the cause of Civil Rights.

But while Motown’s links to Dr. King’s campaign may have been almost invisible to the outside world at times, there is no doubting the company’s commitment. From its artists to its founding father, Berry Gordy Jr., Motown celebrated Dr. King’s work wholeheartedly – with soul, you might say. It released albums of his most pivotal speeches, and their words, recorded for posterity by Motown, still resonate.

The company’s first two albums of King’s speeches rank among the most iconic images in Motown’s huge catalogue, but don’t contain a single element of the company’s trademark sound – apart from its sometimes underestimated Black consciousness. Motown was willing to subsume its corporate identity to a greater cause. These records were all about getting Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s message across.

Detroit and The Walk To Freedom

The first record captured Dr. King’s speech at 1963’s The Walk To Freedom in Detroit. For decades, Detroit had been the destination of preference for many African-Americans in the south who were longing for a better life in the north. Detroit was booming, with 10 major automobile manufacturing companies. Production-line work at General Motors, Ford, or Fruehauf trailers was hard, repetitive, and noisy, but compared to breaking your back to earn cents as a sharecropper or farm hand in the south, it was rewarding and regular. Not only that, but Detroit was seen as a model for race relations, and Black businesses were springing up to cater for the new population. Some would make an impact way beyond the city – none more so than Motown, the record label founded in 1959 that brought a new, arguably “industrialized,” soul sound to the world. Detroit’s reputation for integration, which attracted Dr. King, who believed in equality of opportunity rather than separate development, had an echo in the way that Motown was marketing Detroit’s music to the world. Motown was not selling out, it was buying into a bigger, wider audience.

It might seem strange that The Walk To Freedom, a protest march hailed as “the largest and greatest demonstration of freedom ever held in the United States,” should take place in a city where African-American people could thrive. This was a metropolis where powerful local politicians could take the stage alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr; the city Mayor could boast of racial progress, and its police chief would promise the Civil Rights figurehead there would be no dogs or water cannons turned on the marchers – unlike in Alabama, where the movement’s charismatic leader had been jailed for exercising his democratic right to protest.

But behind the gloss and boasts, Detroit was a divided city. Subtly so, perhaps, but unequal all the same. Housing policies that dated to the 30s had drawn lines on a map: Black residents here, white there. Facilities were likewise uneven, the suburbs were white and well-served, the inner-city housing projects accommodated Black people, had fewer amenities and were often in a poor condition. Even when an African-American managed to break into a middle-class earnings bracket, bank loans were denied to him (and it was a him – women were routinely refused) or granted only at a punitive interest rate.

It is no accident that Berry Gordy borrowed the few hundred dollars he needed to found his empire from his family, not a bank. Government-supported mortgage schemes supposedly meant for everyone were frequently blocked to Black people at a local level. The usual indicators of poverty, such as ill health and unemployment, ran higher in Black neighborhoods. A better life in Detroit than Alabama? Sure. But everything is relative. Dr. King knew there were still doors shut to his people.

On June 23, 1963, Dr. King led 150,000 marchers through Detroit to Cobo Hall, the three-year-old convention center named in unintended grim irony after Albert Cobo, the Republican mayor of Detroit for most of the 50s, who had fought against integrated neighborhoods and complained about a “negro invasion” of white districts. An audience of 14,000 was gripped by Dr. King’s address, which came to be known as The Great March To Freedom. It should have been remembered as one of the greatest speeches of the 20th Century – and would be more widely acclaimed as such had the great orator not delivered a similar message in Washington D.C. two months later.

The Great March On Washington

The Washington event drew history’s gaze more acutely because Dr. King was campaigning in the United States’ political epicenter. The world’s media was in permanent residence. Delivered a little over a mile from the White House, his words could hardly be ignored by President Kennedy, who was already sympathetic to the cause, though his Civil Rights Act was opposed in the Senate for 54 days solid and did not become law until nearly eight months after his assassination in November 1963.

While Washington’s establishment spoke grandly of The People, the city remained deeply segregated: some people were more People than others. It was seen as the powerbase of white America, but beyond the marble halls of the elite, African Americans nicknamed Washington Chocolate City, it was so Black. In 1960, nearly 54 per cent of the District of Columbia’s population was African American – it was the first predominantly Black major city in the US. But as elsewhere, the city’s facilities and wealth were chiefly distributed away from its Black districts. So the March On Washington’s primary focus was to protest economic inequality, and it sought to rebalance access to work, education and housing, among other demands.

The march drew 250,000 people to the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963, and it was here that many people believe Dr. King gave his first “I have a dream” speech. The great man did use those words, but in this form: “I still have a dream,” a direct reference to the fact he had revealed this hope at the earlier Detroit rally.

The Motown records

Dr. King’s dazzling and deeply moving words from both speeches were released on record – appropriately by Motown, which was starting to build the sort of global reputation for the city’s soul music that previously only its cars had enjoyed. Motown issued the album of the Detroit speech in August 1963, titling it The Great March To Freedom. The label had negotiated a 40-cents-per-copy royalty and a $400 advance for the album with Dr. King, a generous deal for a record with a wholesale price of $1.80. Dr King refused the royalties, instead asking for the payments to go to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Berry Gordy also made a $500 donation to the organization and Motown acts appeared at its fundraisers.

In the book Motown: The Sound Of Young America, company insider Barney Ales has admitted that distributors weren’t keen on The Great March To Freedom, being more au fait with promoting records that promised to liberate your feet and libidos than your oppressed souls. The company probably pressed 10,000 copies, with half of that number returned unsold. America’s record-buyers did not know what they were missing.

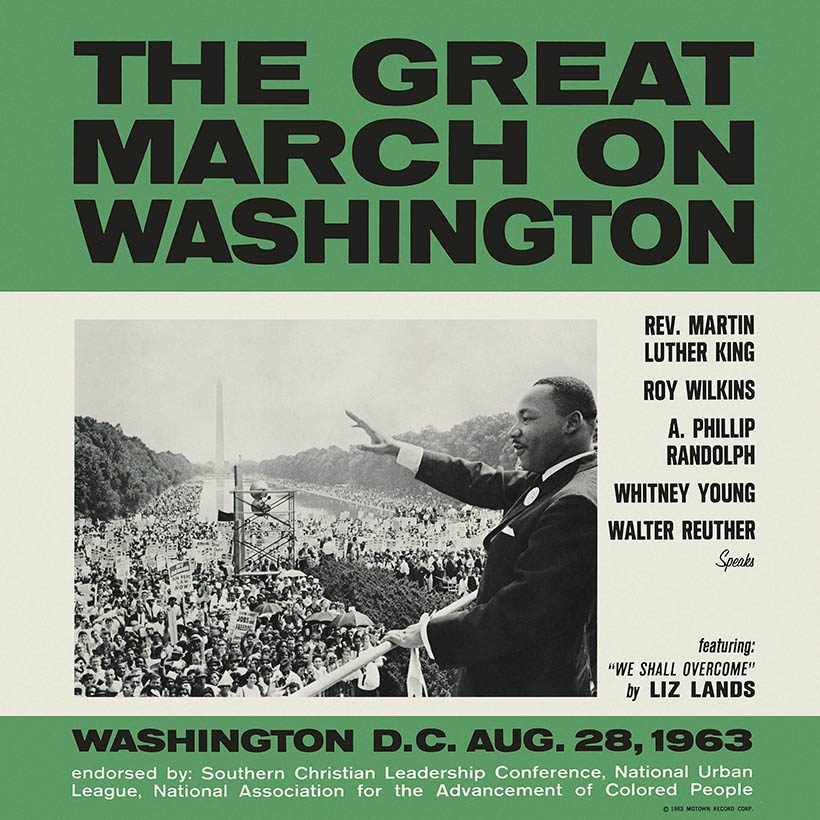

Undeterred, Gordy was not done with promoting Dr. King’s message, rightly believing these albums would earn their place in history. The Great March To Freedom was soon joined by a further set, The Great March On Washington. This made sense: the rally in the capital had quickly overshadowed the Detroit event, drawing far more publicity. The Great March On Washington also featured other speakers from the day, union leaders A. Phillip Randolph and Water Reuther, and Civil Rights campaign mainstays Roy Eilkins and Whitney Young, plus a rousing version of “We Shall Overcome” by Liz Lands, a gospel singer and aspiring R&B artist whose five-octave range won her a Motown contract that year.

Motown retained its interest in Martin Luther King and Berry Gordy Jr was a discreet financial contributor to the cause. Shortly after Dr. King’s shocking assassination in 1968, excerpts from the Detroit speech were issued as a single, “I Have A Dream.” The album Free At Last followed, while Motown’s Black Forum imprint, a label established to preserve and propagate the message of Black rights, issued the acclaimed Why I Oppose The War In Vietnam in 1970. It won the Grammy for Best Spoken Word Recording the following year. (It was only the second time the company had landed a Grammy, the first being The Temptations’ Best R&B Performance award in 1968 for “Cloud Nine.”)

Motown’s artists were inspired

Motown’s connections with Dr. King were more than just a business matter. Berry Gordy was among the inner circle who personally supported and advised Dr King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, following her husband’s cruel and untimely murder. More than this, Motown’s artists found inspiration in Dr. King’s life and work. Shorty Long’s elegant 1969 single “I Had A Dream” drew heavily on his words in Detroit. Stevie Wonder’s joyous 1980 tribute, “Happy Birthday,” which delivered unstoppable momentum to the campaign to create a national holiday in honor of the Civil Rights leader’s birthday, was pressed with excerpts from Dr. King’s speeches on the other side. Tom Clay, a Detroit DJ, created a remarkable cut-up single juxtaposing “What The World Needs Now Is Love” and Dick Holler’s protest ballad “Abraham, Martin And John” with excerpts of speeches from Dr. King and John F. and Bobby Kennedy, and it provided a much-needed and musically arresting No. 8 smash for Motown’s new subsidiary MoWest in 1971. The year before, Marvin Gaye had enjoyed a UK Top Ten hit with a beautiful cut of “Abraham, Martin And John” which carried more than a few hints of the new direction which would deliver his masterpiece, What’s Going On. Gaye was particularly affected by the killing of Dr. King, and stated: “I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.”

Diana Ross was aware that her fame could allow her to speak to a mainstream audience about Dr. King’s work which was perhaps indifferent or ignorant about his message. On the night of his assassination, The Supremes appeared on The Tonight Show, and Ross directly mentioned the tragedy. Seven months later, in November 1968, Ross again broached the subject while starring on a TV showbiz institution, speaking of Dr King during a monologue at London’s Royal Variety Performance. This was controversial issue in the UK as Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, and Princess Anne were in the audience, and the Royal Family is supposedly above potentially contentious political matters.

One of the greatest orators of the age

Motown released The Great March To Freedom and The Great March On Washington on its mainstream R&B subsidiary, Gordy. Their front sleeves did not bear the label’s logo, as would normally be the case. Instead, a dramatic, newsy-looking layout emphasized the import of their contents. The first of the two records was also in a gatefold sleeve – four years before this became a rock music “innovation” – featuring an impressive photo of the mass of protesters in Detroit. Motown, or more accurately recording engineer Milton Henry, captured the atmosphere beautifully. These releases are not hi-fi experiences, but they are real: you can hear the vastness of the crowds in Detroit and the capital, and the rapt attention the people gave Dr. King. It’s not hard to imagine the scene.

Needless to say, Dr. King’s words, which speak of peace, dignity, and freedom as well as the struggles ahead, became keystones of the Civil Rights era. His impeccable, perfectly paced, utterly measured delivery still sounds like the work of one of the greatest orators of the modern age. This is a voice that remains relevant, speaking of matters that remain unaddressed. Some of the terminology may have changed, but the power of Dr. King’s message is totally intact.

The legacy

While freedom still remains unattainable for so many, hope remains. Detroit has been struggling for years: its population has tumbled to less than a million, unthinkable when Dr. King spoke, and political power in Washington has fed on and even encouraged inequality in recent years. But the words Dr. King delivered on those two glorious days continue to resonate. Motown and especially Berry Gordy were highly prescient to realize the pivotal nature of Dr. King’s campaigns. In ensuring his words could be heard down the generations, these historic records of his work gave the Civil Rights trailblazer a platform that has lasted far beyond his all-too-short lifespan. Previous generations had not been able to hear their words of their leaders in the struggle. That had now changed: Motown made sure you could hear them in your own home as often as you needed to. These speeches helped provide inspiration for President Obama and the Black Lives Matter movement, both of which have updated and developed his mission by peaceful means. Though Dr. King’s dream remains some distance short of reality as yet, the Great March goes on.