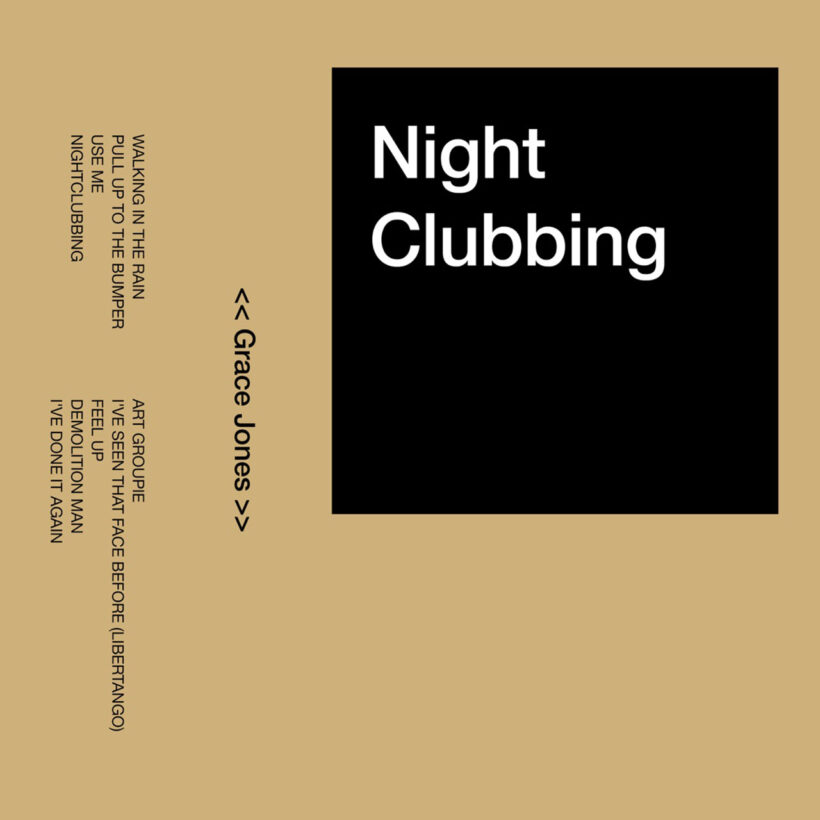

‘Nightclubbing’: Grace Jones Pulls Up To The Bumper

How the Jamaican-born singer embraced her roots and took control of her sound.

The fifth album by Grace Jones, 1981’s Nightclubbing, is a self-assured, uncompromising, and alluring classic – a fusion of Jamaican rhythms and musicality with European post-punk grit. It was held together by Jones’ unmistakable vocals, monotone one minute, flirtatious cackle the next. As the new decade kicked into gear, Jones was the full package, a pop sensation whose voice matched the strength of her image.

Jones began the previous decade by moving from New York to Paris, where she established herself as one of the planet’s most in-demand models. In 1977, she signed to Island Records, who paired her with disco godfather Tom Moulton, the producer credited for innovations including the remix and the 12” vinyl single format. Jones took singing lessons and embraced the disco scene, moving back to New York and becoming a regular on the Studio 54 dancefloor. Even so, the three albums she recorded with Moulton – Portfolio (1977), Fame (1978) and Muse (1979) – failed to truly break through and Jones was yearning for a change.

Listen to the Grace Jones album Nightclubbing now.

“Disco was squeezing me into a room that was looking tackier and tackier, and I was worried I was going to be trapped,” Jones wrote in her 2015 memoir, I’ll Never Write My Memoirs. “[The albums] were becoming his vision more than mine. They all followed the same formula – the thumping dance, the showboating Broadway, some inevitable French spice, the glossy, tightly arranged Philly frills. There were songs and medleys that were souvenirs of the Studio 54 era, and they had titles that referred to my modeling career and to my association with artists and photographers. I was becoming the decoration, and I was getting bored with that.”

Compass Point

Island Records boss Chris Blackwell was keenly aware of Jones’ potential, not to mention the changing musical landscape. Feeling that Jones had not truly found her voice, Blackwell hit upon the idea of returning the Jamaican-born artist to her roots. He persuaded Jones to record at Compass Point, his new studio complex in the Bahamas, where he would build a band around her.

“I wanted Jamaican music,” Blackwell told Hot Press in 2022. “I wanted Sly & Robbie, and the percussion [Uziah ‘Sticky’ Thompson]. I wanted rock guitar, which was Barry Reynolds, who’d played on Marianne Faithful’s Broken English, and [on keyboards] Wally Badarou… I invited them all down to meet at Compass Point and for the first couple of days it didn’t look like it was going to do too well. Sly & Robbie can be a bit rough and ready and Wally was this well-dressed gentleman. They didn’t really hit it off so I put up the photograph of Grace on the wall and told everyone that the records should sound like this photo. That gave some focus and two or three days later it was like a love affair between all these musicians from different parts of the world.”

In I’ll Never Write My Memoirs Jones credited Blackwell with helping her find the sound she’d been craving: “Chris took all my different worlds and stuck them all together to create the Compass Point All Stars – the erotic French side, the acid-tripping rock’n’roller, the Jamaican drum and bass, the androgynous, android electronics – it was magical, this assembly of pieces that fitted together.” Sessions began in early 1980 and were so productive that enough material was recorded for two albums, 1980’s Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing. With that massively blown-up photograph looming over them, the All Stars and Jones quickly established the kind of working relationship that Jones had been craving. “It was perfect for me, the groove they hit instantly, the mix of the organic and the electronic,” Jones revealed. “It fit me like a bloody glove. We fell into a pure, instinctive groove that didn’t need hours and hours of preparation. They set up the groove and worked out the beats, and I got in the chariot – but I was out front, leading the procession, behind when I needed to be, sometimes ahead, sometimes right on the moment.”

Pull Up To The Bumper

Nowhere was Jones’ new method of working more effective than on the spicy hit single “Pull Up To The Bumper.” The song started life as a colossally funky groove recorded by Sly & Robbie during those initial Compass Point sessions. Blackwell didn’t feel the track fit with Warm Leatherette’s vibe, deeming it “too R&B” and it ended up appearing as “Peanut Butter,” an instrumental B-side to “The Kick (Rock On),” a 1981 Junior Tucker single.

Jones was affronted by one of ‘her’ tracks being used elsewhere and, with a little help from a friend, wrote a lyric loaded with innuendo. “My friend Dana Mano came up with the idea of “pull up to the bumper, baby,” which sounded nicely naughty, and we started to write some silly stuff that sounded good to go with it. There was a double meaning to it, and I liked to write lyrics that had double meanings… So, we have a car, and it’s long, because it’s a limousine, speeding down a Manhattan avenue… and you want to keep it clean, so you wax it and rub it, giving it a shine, and it’s hard to park, because we’re in the city, and it’s so big, so you have to squeeze it into tight spaces… You make it fit, and it is such a great feeling… If you wanted, you could imagine that I’m not singing about a car at all. But that’s up to you. If you think the song is not about parking a car, shame on you.” However you choose to interpret it, the seductive and playful “Pull Up To The Bumper” hit a sweet spot on dancefloors and eventually became one of Jones’ signature songs, peaking at No. 12 in the UK and reaching No. 2 on the US Billboard Hot Dance Club songs chart.

Nightclubbing, the album

Nightclubbing’s title track showed an entirely different side of Jones. Written by David Bowie (music) and Iggy Pop (lyrics) and originally appearing on the latter’s 1977 classic The Idiot, “Nightclubbing” was transformed by Jones and the Compass Point All Stars from Pop’s doomy glam stomp into a chilling dub track. In keeping with the original, Jones’ deadpan rendition doesn’t suggest excitement at the prospect of a night on the tiles, but it does create an intoxicating ambiguity. It was an approach that set her apart, as she later explained, “After the disco albums, I had decided that I was going to sing in my way, not try and become a conventional pop singer. I had found my voice, and once I started singing along with the heavy bass and machine-gun drum of Sly and Robbie, it was actually an advantage that I had the voice that I did. There was no place for a standard soul or funk voice in that sound. My voice was perfect for it, somewhere between half-speaking and half-singing, between expressing emotion and not expressing anything, between telling a story and remembering a dream. It would be better for me to have a voice that suited my appearance, and once Chris had put together these musicians, I found my place. Now that I had lowered my voice, I didn’t need anything sweet around me. I could move into other spaces.”

Having given herself permission to explore the parameters of her artistry, Nightclubbing saw Jones genre-hop with abandon. “Walking In The Rain” may have been a cover of a track from Australian band Flash & The Pan’s eponymous 1979 debut album, but Jones performs it like it was written for her, provocatively purring “Feeling like a woman, looking like a man” over Robbie Shakespeare’s deep, exploratory bassline and Sly Dunbar’s insistent beats. The Jones original “Art Groupie” also nodded to her homeland, its Jamaican rhythm decorated with jaunty and infectious synth parts. Meanwhile, “I’ve Seen That Face Before” was an inspired reworking of “Libertango,” written by Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla in 1974, which the Compass Point All Stars performed as if at dub night at the Moulin Rouge, with Jones the provocative compere. Elsewhere, Bill Withers’ “Use Me” became a bass-heavy anthem of empowerment and “Feel Up” had a heady groove that worked wonders at the Paradise Garage when remixed by pioneering DJ Larry Levan.

While Warm Leatherette signified a startling change of direction for Jones, Nightclubbing captured an artist full of confidence and in total control. Nothing has sounded quite like it since.