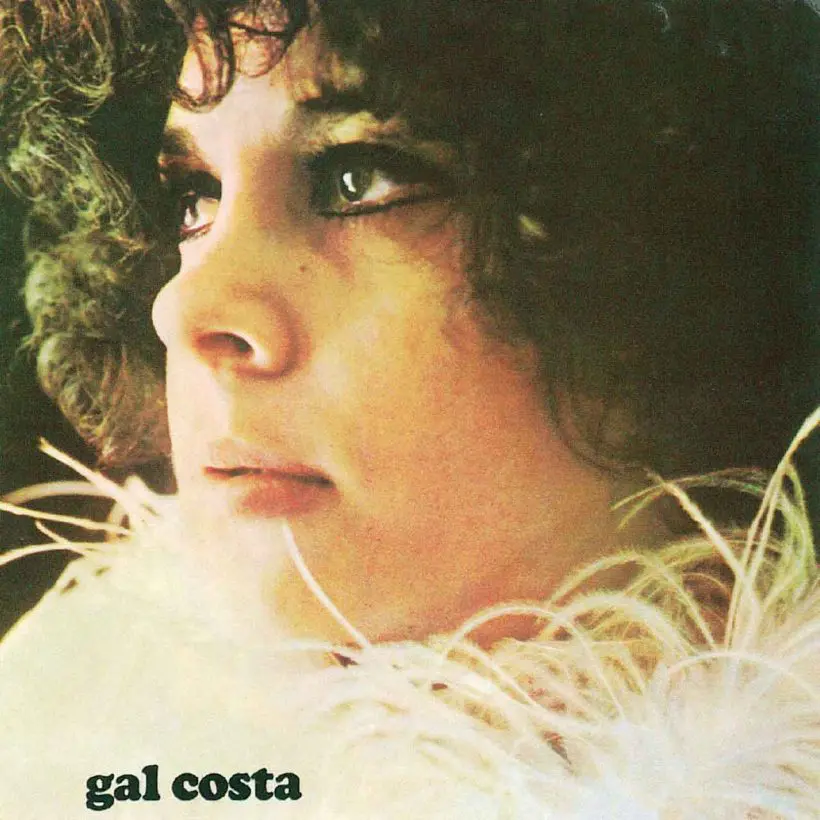

‘Gal Costa’: A Landmark Album Of Brazilian Tropicalia

Her 1969 self-titled album remains a landmark of Brazilian pop.

Following a US-backed military coup in 1964, many young artists in Brazil – disillusioned with the apolitical nature of bossa nova – searched for a music that would speak to their contemporary world. By the late 60s, a group would answer the call through a movement known as Tropicália. These artists – chiefly Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes, and Gal Costa – sought a “universal sound”; a merger of local and international styles that was both cosmopolitan and distinctly Brazilian. Their fusions of bossa nova, psychedelia, and rock ’n’ roll remain totally unique.

Among the most important works of this period was Gal Costa’s 1969 eponymous album. Costa began her career as a bossa nova singer before joining the “tropicalists” in 1968. From the first moment of this album, the transformation is clear. “Não Identificado” begins with harsh waves of static before fading into bright organs and swooning orchestral arrangements by Rogério Duprat.

Listen to Gal Costa’s 1969 self-titled album now.

Over the shifting rhythms and bombastic horn arrangements of “Lost in Paradise,” Veloso’s surreal lyrics reference cultural identity in post-colonial Brazil. “Se Você Pensa” and “Vou Recomeçar” delve into the psych-funk excursions of pop star Roberto Carlos. With fuzzed-out, wah-drenched guitars and tight percussion, the influence of James Brown is obvious here.

On the remarkable “Divino, Maravilhoso,” Costa is delightfully unhinged, channeling another of her American inspirations: Janis Joplin. Over a bustling arrangement by Veloso and Gilberto Gil, Costa details the threat of violence under the junta: “attention to the windows up high / attention when treading the asphalt, the mangrove / attention to the blood on the floor.”

“Que Pena (Ela Já Não Gosta De Mim),” sees Costa dueting with Veloso on a lilting tale of lost love; the political undertones of Tropicália substituted for the simple romance of bossa nova. “Baby,” meanwhile, remains the album’s most cherished hit. Atop soaring string arrangements, Costa’s voice holds a powerful tenderness. Depending on one’s interpretation, it’s either unashamedly sentimental and detached from its political context, or an intentionally saccharine, ironic rebuke to consumerist society. Veloso’s lyrics are typically oblique, allowing for either reading to make sense.

If there was one guiding principle of the Tropicália movement, it was the freedom to be many things at once. Their music was both popular and avant-garde, politically principled but undogmatic, distinctly Brazilian but syncretic, lyrically piercing but ambiguous. Gal Costa’s self-titled album remains a paragon of Tropicália and a landmark of Brazilian pop.