‘Etcetera’: Why This Unsung Wayne Shorter Album Deserves More Ears

An overlooked gem, ‘Etcetera’ only gets better with time.

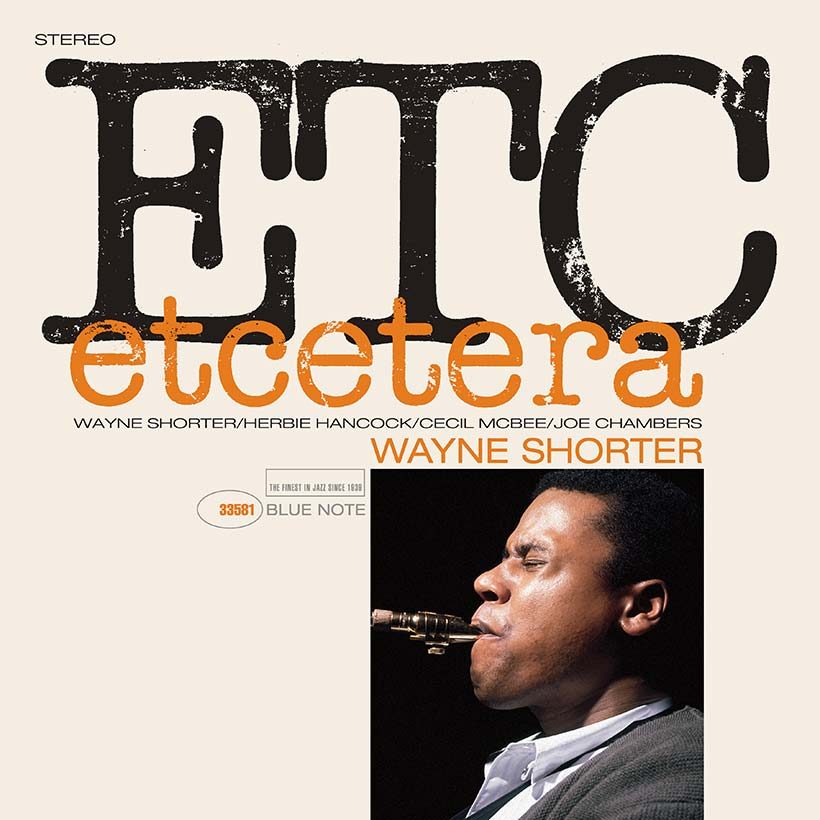

Saxophonist-composer Wayne Shorter recorded Etcetera, one of his most overlooked and underrated Blue Note albums, on Monday, June 14, 1965. Though recorded during a fertile period for both the saxophonist and the record label launched in 1939 by producer Alfred Lion, the five-song album didn’t surface for another 15 years, when, in 1980, producer Michael Cuscuna liberated it from the vaults to share it with the world. But even though Etcetera has been available for four decades, it has never received the exposure or attention it deserves.

Listen to Wayne Shorter’s Etcetera on Apple Music and Spotify.

The context

So why doesn’t Etcetera command the same reverence as other Wayne Shorter albums of the mid-60s, such as Speak No Evil and The All Seeing Eye? And why did it take so long to see the light of day? Such was Shorter’s creativity in the 18-month period between April 1964 and October 1965 – when he recorded six albums in quick succession – it’s possible that Blue Note couldn’t keep up with him. Rather than glut the market, perhaps Etcetera – which was a more low-key affair than some of Shorter’s other LPs from the period – was left on the shelf and then overlooked in favor of later sessions.

When he recorded Etcetera, New Jersey-born Shorter was 32 and a few months into his tenure with the famous Miles Davis Quintet, a pathfinding band for whom he would eventually go on to become the main composer. With Miles, Shorter had recorded the album ESP (composing its title track) in January 1965, and then in March of that year, he recorded a sextet album for Blue Note called The Soothsayer (which, like Etcetera, was shelved until a later date, surfacing in 1979).

For the Etcetera session, Shorter recruited fellow Miles Davis band member, pianist Herbie Hancock, along with bassist Cecil McBee (with whom the saxophonist had worked the previous year on trombonist Grachan Moncur’s Blue Note album Some Other Stuff) and drummer Joe Chambers, who would continue to work with Shorter on his next three albums (The All Seeing Eye, Adam’s Apple, and Schizophrenia).

The music

Stylistically, Etcetera’s opening title track inhabits the more abstract, post-bop landscape that Shorter was exploring with the Miles Davis Quintet during the same timeframe. It is distinguished by a yearning clarion call-like theme constructed from a set of repeated saxophone motifs. Following Shorter’s pithy solo, Hancock enters with something more discursive, avoiding blues and bop clichés in favor of melodic and harmonic surprises. Joe Chambers also has a spell in the spotlight near the end, blending kinetic power with rhythmic subtlety.

In sharp contrast, the ear-caressing “Penelope” – one of Shorter’s finest ballads – is calming and pensive. Its slowly uncoiling, serpentine melody is both beautiful and bewitching, stylistically recalling the earlier “Speak No Evil” and anticipating the later “Nefertiti,” recorded with Miles.

Exhibiting similar musical DNA is “Toy Tune,” a bittersweet, slightly subdued swinger driven by McBee’s walking bass and Chambers’ crisp drumming. After stating the main theme, Shorter takes a long solo but never deviates too far from the contours of his original melody. Herbie Hancock then steps out with a scintillating improvised passage that sparkles with melodic clarity and playful ingenuity.

Strummed chords from Cecil McBee’s bass open the album’s only cover, a retooling of noted composer/arranger Gil Evans’ tune “Barracudas” in 6/8 time (the composer had recorded it in 1964 as a large ensemble piece called “Time Of The Barracudas,” which appeared on his Verve album, The Individualism Of Gil Evans, and which also featured Wayne Shorter). Shorter’s version reimagines the tune in a quartet setting and features stunning solos from both himself and Herbie Hancock, while McBee and Chambers drive the tune forward with a maelstrom of polyrhythms.

Etcetera closes with its longest cut, the modal-flavored “Indian Song,” which is an original Shorter number delivered via a mesmeric loping groove in 5/4 time. Cecil McBee’s repeated ostinato bass motif establishes the mood and tempo before Chambers and Hancock enter, followed by Shorter, who enunciates a snaking Eastern-tinged melody three times before breaking off for an exploratory solo that sporadically keeps returning to the main theme. The rhythm beneath him ebbs and flows, mirroring the rise and fall of intensity in Shorter’s improvisations. Hancock takes the second solo, his foraging piano underpinned by excellent drum work from Chambers, while McBee keeps plucking the same bassline until, at around the nine-minute mark, he solos, roaming more freely before resuming the main groove that prompts a recap of the main theme.

The Tone Poet reissue of Wayne Shorter’s Etcetera can be bought here.