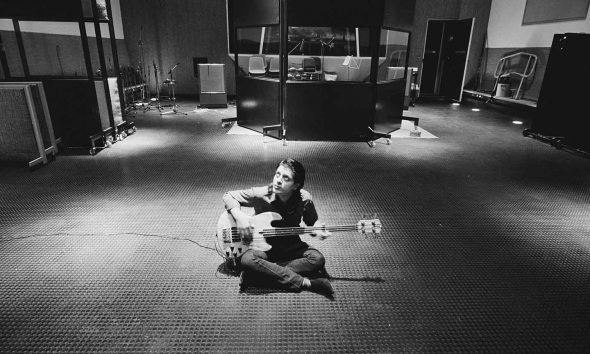

Eric Bell Interview: ‘Everything About Thin Lizzy Seemed To Be About Timing’

The Thin Lizzy co-founder and guitarist reflects on the early years of the legendary rockers.

Guitarist Eric Bell got his start musically in Van Morrison’s band, among periods playing with a host of Irish showbands (traditional/pop-orientated dance acts). But it wasn’t long before Bell followed his musical instincts in 1969 to form Thin Lizzy with Philip Lynott (vocals, bass) and Brian Downey (drums). Bell’s distinctive style was one of the things that set Lizzy apart from the early 70s set, complementing Lynott’s songs with lilting beauty (“Sarah,” “Little Girl In Bloom”) and thrilling riffs (“The Rocker,” “Mama Nature Said”). The strain of life on the road took its toll, however, and Bell left the band after their third album, 1973’s Vagabonds Of The Western World. Over 50 years later, Bell spoke to uDiscover about his time with the pioneering and beloved rockers.

Watch the official video for Thin Lizzy’s “Whiskey in the Jar.”

Before Lizzy you were playing in the popular Irish show band The Dreams, what made you leave them?

Before The Dreams I was living in Belfast, working during the day and playing the blues at night. I had about 14 jobs and I was fired from them all, apart from one at the shirt factory. I just couldn’t handle the nine to five, it wasn’t part of me at all.

The Dreams paid really good money, we stayed at the best hotels, everything was very professional. But I was Jekyll and Hyde. On my nights off, I’d be at home smoking a bit of dope, drinking cheap sherry, and listening to Hendrix, Cream, all that type of stuff. Then I’d be playing “Simple Simon Says” with this showband. I thought, “Man, I’ve gotta get out of here, I want to actually play.”

I was in the rehearsal room one day and Skid Row were practicing downstairs. They were playing this blinding music. Absolutely incredible. Gary [Moore, Skid Row and future Thin Lizzy guitarist] said, “What are you doing in a showband? Why don’t you get out and play?” It certainly helped me make up my mind.

The Dreams were good musicians, but they didn’t want me playing guitar as I wanted, they sort of kept me in a cage. I saved up money, because I knew that I was gonna leave at some point, but it took me a while to make up my mind. When I finally told the manager, he thought I was making a big mistake. It was probably the biggest risk I ever took in my life.

The next step was forming Thin Lizzy, how did that happen?

I was sitting at home thinking, “What am I gonna do? You’ve got to go out and hustle, look for musicians.” I used to get the bus into Dublin city centre and go into all the bars, just to see if there were any musicians about. It was crazy. I’d go into bars on Grafton Street, which is where the younger people would hang out. I’d walk over, butt into their conversations and say, “Oh, hello, I’m looking for a bass player and drummer.” I didn’t know what else to do. I still had a showband haircut and suit, so some of these guys thought I was from the drug squad, ’cos I looked so straight. It was soul destroying.

I knew Eric Wrixon a bit, we were both from Belfast, he played in the original Them with Van Morrison and was in a showband called The Trixons. One night, I’m in The Bailey just off Grafton Street when Wrixon walks in and says, “Hi, Eric, what are you up to?” I said, “I’ve just left The Dreams.” That’s funny,” he said, “I’m thinking of leaving the band. What are you doing tonight? The drinks are on me.” So we started there. Then the pubs started closing and he said, “Do you want to go to a club?”

There were seven good clubs in Dublin and for some reason – to this day, I don’t know why – we went to Countdown Club. Eric offered me a half tab of LSD, which I took. We were standing at the bar and things started getting a bit strange and this band came on, which was a real surprise to us. It was Orphanage and they were really good. Philip was the singer; he didn’t play the bass then. Brian Downey was on drums and just blew me away. I didn’t even look at Philip; I was watching Brian all night.

How did you approach them?

They took a break, so I went to the changing room and knocked on the door. It was only Philip and Brian; the bassist and guitarist had gone to the bar. They said, “Can we help you?” and I started giggling at everything. They said, “Are you OK?” I said, “Yeah, it’s my first trip on acid.” They looked at me in disbelief because I looked real straight.

I told them I was looking for a bass player and a drummer, and they suggested I go to The Zodiac, ’cos that’s where all the musicians hung out. I thanked them and was just walking out the door when Philip called me back.

This is where the whole thing started. He said, “Listen Brian, do you fancy forming a group with Eric?” Brian wasn’t into it: “Nah, we should stick with Orphanage, we’ve got a few gigs booked.” I said, “Well, fair enough.” And as I’m walking out the door, Philip stops me again and says, “Come on, man. Let’s form a group with Eric.” This time, Brian said, “OK, we’ll give it a go.”

What made you realise how talented Philip was?

He came to my flat with a tape of his songs, which were excellent. “Dublin” was on the tape, and “Chatting Today.” I immediately knew this guy was the real thing, there was no doubt about it. When I first heard his songs, I knew there was room for my playing because they were so melodic. In fact, Philip used to sometimes tell me, “You’re too friggin’ melodic.” Because I’d been with a showband, I had a lilt to my playing that a lot of rock guitar players didn’t have. I worked for three different showbands so spent about six years of my life playing Irish stuff. When I started playing blues and rock, a little bit of jazz, the showband was still in me, which gave my playing something different.

We started rehearsing and Eric Wrixon turned up with keyboards, though I wanted a three-piece band. Anyway, we started becoming quite popular very quickly around Dublin. We’d play a place one night and then, about six weeks later, we’d play it again, and there’d be a big crowd on the street.

Me and Philip got a house together in Castle Avenue, Clontarf. After that our girlfriends moved in, then Eric Wrixon – he’d left the band by that point. It was a really up-market area, so you can imagine the looks that we got. We could rehearse every day because we were living together. Well, Brian still lived at home. But he might as well have lived with us because he was over every day, working on songs.

Was Philip a good housemate?

He was a very gentle guy, easy to be with, but very determined, he had lots of energy. He would push it and push it. When people used to ask, “What do you want to be?” He’d say, “I want to be rich and famous.” That’s all he ever said, there was no discussion.

How did you start contributing to his songs?

I’d be sitting on the sofa and Philip’s bedroom was downstairs. Now and again, he’d stroll in, probably with a joint or a cup of tea. I’d be sitting playing acoustic guitar and he’d say, “Is that yours Eric?” I’d say, “No, it’s The Byrds or Deep Purple,” or whatever. If it was one of mine, he’d say, “Come on” and I’d go down to his bedroom. He’d have an acoustic guitar, I’d have mine, and we would sit there working on it, for quite a long time sometimes. He’d say, “I’ve got this riff, I’ve got these chords, but I don’t know how to go from here to there.” So I’d be racking my brains to try and come up with something. It was great because I had to think in an original way. I could put anything in there, as long as it fit. So that’s the way we worked on a song like “The Rocker.” I think one of the reasons we took off so quickly compared to other groups was that we were living together so we were working on our music every day.

We would play stuff like The Rolling Stones’ “Street Fighting Man,” and very slowly put original songs into our act. Then Philip started making shapes on stage. He’d have the bass pointing out to the crowd, and because he had these ridiculously long legs and skin-tight jeans, it was a striking look. Myself and Brian looked the part as well, I grew my hair long. Brian started wearing different clothes. All these changes were taking place.

Next came the move to London in 1971, was that an eye-opener?

It was mind blowing to say the least. I couldn’t handle London at that point – the crowds, the nightlife. I used to wish I was back in Ireland. Philip adjusted to London and so did Brian, better than me. The competition was incredible, there were so many groups there.

Our manager started getting us gigs as a support act with people like Rod Stewart, Status Quo, T. Rex. We were probably the top band in Ireland at that point. When we moved to London, nobody knew who we were, so we had to start all over again. Half the crowd would walk out when we came on because they wanted to see the main act, we had to live with that, but we became more confident on stage. Then we played in Germany, Japan, Sweden, Denmark, France – that was all completely new to us.

I was in a bad place at that point though, there were lots of things going on in my private life. Our management had us out all the time, playing some really poxy places. One night after a gig Philip threw his bass on the on the floor and sat there with his head between his knees. Our road manager came in and said, “Hey, man, what’s wrong with you?” Phil said, “How the f— do you get off this circuit? All we do is go up and down the motorways and half the clubs aren’t worth playing.” The guy said, “You need a hit record,” and walked out. We sat there going, how do we do that?

After two fine albums that didn’t sell, you got that hit record with “Whiskey In The Jar”…

It changed our life, there’s no doubt about it. Again, it was a fluke. Everything about Thin Lizzy seemed to be about timing. I could’ve kept walking the night I met Philip and Brian. There were these little moments.

One day, we were rehearsing in The Duke Of York, the pub we used once a week. We were trying out this song and it just wasn’t happening. We were gonna pack up and go home and Philip said, “No we’re paying for this place, we’re gonna get our money’s worth.” He started messing about, took off the bass, put on a guitar and started singing these corny songs just as a laugh. Then he started doing the Irish stuff, as sort of a send up.

I started playing guitar along with him and Brian came in on the drums. The next thing, the door opens and it’s Ted Carroll, our manager, he had a new guitar amplifier for me. So we’re talking about that, and all of a sudden he says, “By the way, what was that song you were playing just before I came in?” We’re just looking at the amp, not taking any notice of him.

“When are you recording your next single?” he said. “In about six weeks.” “Have you got an A-side?” “Yeah, ‘Black Boys On The Corner’.” “Have you got a B-side?” “We’re not too sure yet.” “What was that song you were playing?” Phil said, “For f—’s sake. Whiskey in the f—ing jar, we were only messing about.” Our manager says, “I think you should record that.” We were gonna throw him out the window. We left Ireland to get away from “Whiskey In The Jar” and he wants us to record it!

So what changed?

We ended up in the studio six weeks later and “Black Boys On The Corner” came out great. Then everybody’s going, right, what’s the B-side? When our manager suggested it again, we said, “OK, if you promise not to talk about it anymore, we’ll try it.” So me and and Philip went in with two acoustics, with Brian on the drums, Philip sang a rough vocal and it was recorded. We listened to it and everybody said we really had something. Philip said, “I have to put the bass guitar on yet.” And for some strange reason they said, “No, let’s leave it without the bass.”

I hadn’t a clue what to do about the lead guitar. I tried a few things and they were naff, so I took a cassette of it home and we went out gigging again. Three or four days passed and we’re on a long drive from Wales to London. Philip used to put on cassettes, all different types of stuff – rock, classical, blues, jazz. That night, he put on The Chieftans and I’m in the backseat, tired and stoned. I hear this music coming from the front of the car, I started really enjoying it. I thought maybe I’ll try and emulate the Irish pipes. That night at home, I started working on that A minor chord coming in and then the intro, it took me about an hour to come up with it. Then I had to come up with a riff.

Meanwhile, everybody’s waiting on me to come into the studio, they’re all giving me a hard time. So I put on my commercial head and started thinking, Beatles, Stones, Free, Deep Purple – they all use riffs, which repeat through the song [sings “Satisfaction” and “Day Tripper” riffs], I want to do that. I was usually into ad-libbing but I thought, No, I want to play the game. It took about another 10 days, but I eventually got it. The solo came reasonably easy after that. So they got me a car to the studios. I set up and just played it through.

What happened when it wasn’t initially a hit?

Philip was saying, “I f—in’ told you not to record that shite. ‘Black Boys On The Corner,’ that’s the A-side.” We thought it was a mistake and forgot about it, more or less.

We were in Germany and the gigs weren’t great, we were very tired, working all the time, the band was on the verge of splitting up. One morning we were in some hotel for breakfast and the manager comes in and says, “Good morning, boys, telegram from London.” We open it up and it says, “Congratulations boys. ‘Whiskey In The Jar’ is No 22 in the English charts, cancel all the gigs in Germany and get home.” A few weeks later, our management said you won’t believe it. You’re on Top Of The Pops. I said, “You’re not f—ing serious.” It was in the charts for 11 weeks or something and crept up to No 6 in the end,

What does that kind of success do to a band?

Oh my god, Philip was gone. He was away with the fairies; he couldn’t get enough. Brian loved it as well, but he was a bit cool about it all. I didn’t know what to think, I was going through this ridiculous depression. I’m on Top of The Pops. I should have been as high as a kite, and I was as miserable as sin.

Next came your classic third album, Vagabonds Of The Western World…

The first album was like the best kept secret of the year. We went back to Ireland to tour it and they didn’t have the album in the shops. Phil was going crazy, “We’re over here in Ireland doing a tour to promote the first album and it’s not in the shops.” Then we recorded Shades Of A Blue Orphanage and nobody seemed to like that either. Listening to them now, I think early Thin Lizzy was very original and there’s some good playing on those records, no doubt about it.

Then on Vagabonds, we really started getting our act together. Still, we couldn’t give it away, the English critics had no time for us. They’d say, “Irish three-piece band still don’t know what direction to go in, every track’s different,” and so on. “Maybe they’ll find their own style someday. Anyway, not a bad album, keep at it lads.” That type of attitude was surrounding us at that point.

Around this time you were beginning to grow in confidence as a live band, what changed?

Things started changing when we went on the tour with Slade and Suzie Quatro, that was the beginning of the end in a way. First gig of the tour we walked in and it was a town hall, it wasn’t a club that held 200 people, this place held three thousand, it was just enormous. We’d never played in a place like this ever. We get on stage and we’re checking out Slade’s equipment and thinking, “These guys mean business.” We thought it was a pop group we were on with. Then the first night we met them and they were really good guys.

The place was packed, absolutely stuffed. The crowd had their scarves out, singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone” and all this stuff. Me and Phil were in the corridor talking before we went on and the next minute, Suzi Quatro runs past in tears with her bass guitar. It was like Nero and the gladiators, I swear to God. We went on and we were doing the same show as we did in the small clubs, just standing there and playing. The crowd started booing us and throwing cans of beer and one of them hit Phil’s bass. He said, “For f—’s sake, we’re trying our best, give us a chance.” Then this chant started, “We want Slade.” They just kept chanting. We had to walk off; nobody wanted to know. We went into the changing room, we didn’t know what to say and at that moment, the door bangs open, it’s Chas Chadler, “What the f— was that about?” We were just absolutely speechless. “You’re on here to wake the crowd up, not to put them to sleep. If you don’t get it together, you’re off the tour.” And he slammed the door.

Philip had just been told by his hero Jimi Hendrix’s manager that we were a load of shite, so you can guess what that was like. When the tour started again, we were under this ridiculous pressure to try and put on a show, to throw out some of the slow numbers and pay more rock and all that. And that’s what happened.

What made you leave the band?

I was going through a deep depression. I was taking Librium, drinking whiskey and smoking cannabis – a bit of a combination. I started drinking more because I was depressed and it just escalated. Then I started smoking dope and I’d get paranoid, so I’d drink more. That’s what I was like and I couldn’t stop.

The last gig I did was at Queen’s University, Belfast, my hometown. I was completely out of my tree. One of the reasons being when I got to the venue, there was nobody there. Our equipment and roadies hadn’t arrived yet. This guy comes up to me and shows me to the changing room. Big mistake. There’s a sheet over this big table in the middle of the floor and, of course, I knew what was under it – every drink you could ever think of. I said to myself, Listen, you gotta just take this easy. Of course, an hour later I’m gone. So it’s time to go on and I don’t know who I am or what I’m playing, I walk on stage and I’m completely and totally zombiesville. We start playing, and I just can’t do it. I can’t remember the chorus. I can’t remember the lead work. I can’t remember if I already played the solo or which song we’re playing. There were 1,000 people watching us and this voice in my head says, You’ve gotta get out of here or you’re a dead man.

It went away, but the more I kept playing, the more it kept coming back. Eventually, I threw my guitar up in the air – God love it, I still play it, it’s forgiven me – then I kicked all the amps off the stage and staggered off. Underneath the stage were a load of gymnasium mats and I just collapsed on them. Our road manager Frank Murray crawled underneath the stage and said, “Get on that f—ing stage and finish the f—ing gig.” I said, “I’m gone man. That’s it. It’s over.” They got me under each arm, stood me up, walked me up the steps to the stage and put my guitar on, which was completely out of tune. It must have been horrendous. And I can’t remember anything else.

How do you feel about your time in Thin Lizzy now?

Looking back, obviously, I’ve learned to live with it and sorted it out in my own head. It was just the times that we were living in. One of the things that that you have to remember is that the music business can be a very frightening place. I’ve changed completely, there’s no way you can live like that as you get more mature. I can walk on stage now having just had a pint of Guinness and thoroughly enjoy it. I still love playing the guitar to people. Now, I just can’t believe it. Years later young people are starting to listen to the first three Lizzy albums. We’re getting very good comments about what we did and I think, “Damn right, that was a good little band.”

Watch the official video for Thin Lizzy’s “Whiskey in the Jar.”