‘Empyrean Isles’: How Herbie Hancock Charted New Territory In Jazz

From soul-jazz cuts to avant-garde explorations, ‘Empyrean Isles’ revealed that Herbie Hancock was a jazz icon in the making.

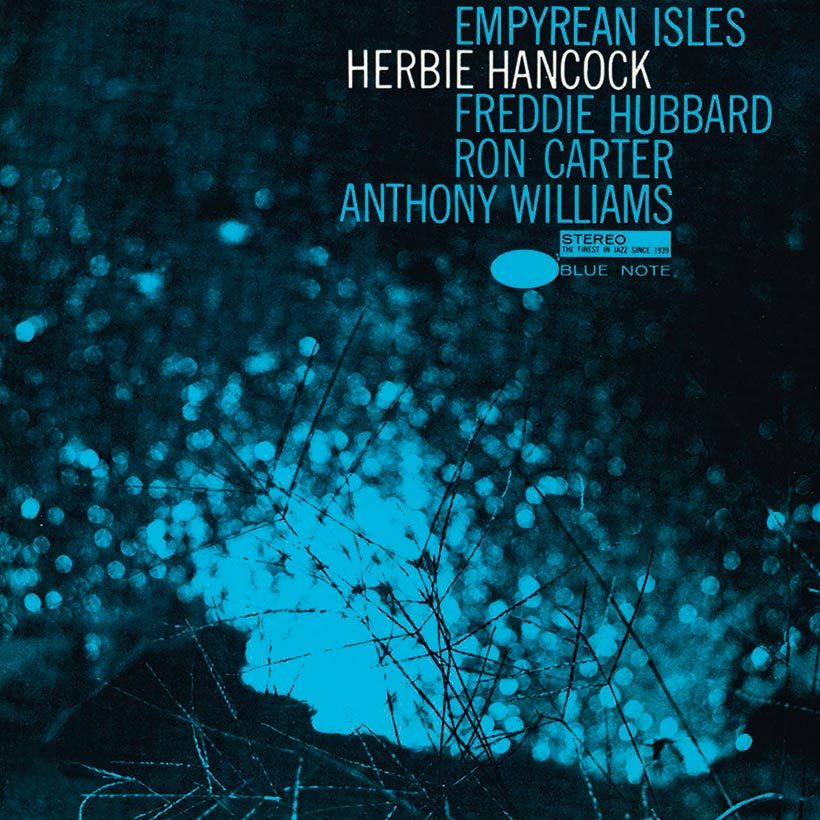

On Wednesday, June 17, 1964, pianist Herbie Hancock went into Van Gelder Studio, in New Jersey, to record what became Empyrean Isles, his fourth album for Blue Note Records.

By then, at the age of 24, the bespectacled, classically-trained Chicagoan was already a rising star in the jazz world. As well as being an integral member of Miles Davis’ groundbreaking quintet since 1963, his solo career was in the ascendant, propelled by “Watermelon Man,” the lead track from his 1962 debut album, Takin’ Off, which had been popularized thanks to a hit version by Latin percussionist Mongo Santamaria.

The concept

Given the simpatico he felt with fellow Miles Davis band members, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams, it was no surprise, perhaps, that Hancock elected to exploit their unique skills on Empyrean Isles, a concept album based on a mythical place, that consisted of four self-penned tracks expressing different facets of Hancock’s musical psyche.

Many jazz albums of the time used a two-horn front line, usually consisting of saxophone and trumpet, but on Empyrean Isles, Hancock, going against the grain – the pianist’s career-defining characteristic – used only a single horn: Freddie Hubbard on cornet. Hubbard, another young lion signed to Blue Note, was no stranger to Hancock’s music and had graced Takin’ Off with his virtuosic playing. But the concept behind Empyrean Isles was more advanced and exploratory than Hancock’s debut, and allowed its protagonists greater space, flexibility, and freedom in regard to improvisation.

The album

Structurally, Empyrean Isles’ opener, “One Finger Snap,” which begins with a fleeting unison theme on cornet and piano, before Hubbard breaks off for a solo, demonstrates Hancock’s propensity to take risks – something that he had learned from working with Miles Davis, who instilled in him the notion that there were no wrong notes or mistakes. Williams and Carter initiate a lightly swinging groove, over which Hubbard lets rip with molten cornet lines while Hancock supports him with subtle staccato punctuation. He picks up the baton from Hubbard, demonstrating his total mastery of the piano with a solo comprising fleet-fingered right-hand melodies. Hubbard returns a burning passage of improv before allowing the spotlight to fall on young Tony Williams, then just 18, who serves up a swirling hurricane of drums and cymbals. After that, the horn and piano return momentarily to state a brief closing motif.

Ron Carter’s elastic bassline propels the midtempo “Oliloqui Valley,” on which Hubbard’s cornet enunciates a short theme prior to a long solo from Hancock over a blithely swinging rhythmic undertow. Hubbard’s solo is incandescent, though the piece loses momentum to allow Ron Carter room for a spacious bass solo which not only underlines his dexterity but also his judicious use of dynamics and nuanced sense of feel.

“Cantaloupe Island” is one of Hancock’s most famous tunes, a jaunty soul-jazz groove with a relaxed vibe that is a companion piece to “Watermelon Man” – only catchier and even funkier, and on which Freddie Hubbard again excels as a soloist. With its blues-infused melody and danceable vamp, it’s undoubtedly the most down-to-earth cut on Empyrean Isles, showing that the pianist could write credible commercial material as well as more abstract, exploratory pieces. Hancock revisited the song, in 1976, on his Secrets album. The original Blue Note version – which the label also released as a single – was sampled by British hip-hop group Us3, in 1993, for their hit “Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia).”

The most radical cut on Empyrean Isles is its finale, “The Egg,” a desultory, avant-garde-style piece initially driven by Hancock’s repeated ostinato piano figure. Essentially, it’s an open-ended vehicle for improv but has a more abstract section in the middle, where the track’s rhythmic impetus dissolves and Ron Carter plays a bass solo with a bow. Hancock then plays a passage of unaccompanied piano, before Carter and Williams reinstate the groove.

The album’s legacy

With its blend of advanced bebop and modal jazz with funk and free improv – all convincingly rendered – Empyrean Isles offered ample evidence that Herbie Hancock was a jazz master in the making.

Revealing himself as a musical chameleon, Hancock would go on to record a welter of albums in an array of styles in the succeeding five decades, but this astounding album, recorded 54 years ago, remains one of the early high points in his long and illustrious career.