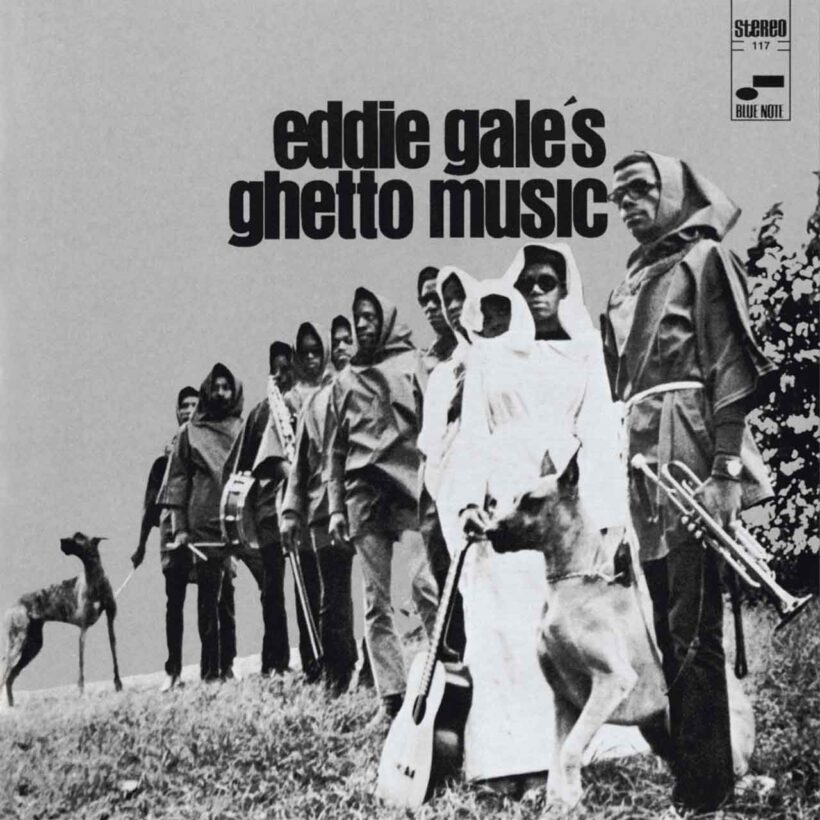

‘Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music’: Jazz Meeting The Moment

One of the most unique albums within the Blue Note catalog, it’s a fierce celebration of Black identity.

Turmoil fundamentally defined the American zeitgeist of 1968. But for Black Americans in particular that turmoil was nothing less than a deluge of violence: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the resulting riots that set Black communities across the country aflame; 17-year-old Black Panther Party member Bobby Hutton’s killing by Oakland police, which inaugurated a deadly cycle of BPP confrontations with law enforcement and its agents; the disproportionate deployment of Black soldiers as combat troops in Vietnam; even down to the workplace neglect that resulted in the deaths of two Black sanitation workers in Memphis, and a subsequent labor strike buoyed by a simple demand for equality and dignity, “I Am a Man.”

Listen to Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music now.

So when the eleven-piece Noble Gale Singers collectively urge, “Stop the rain!”, at the dramatic peak of Eddie Gale’s 1968 recording “The Rain,” it’s with the full weight of the moment behind them. It is an earned climax, both emotionally and musically, within a track that beautifully ebbs and flows from the plaintive solo acoustic guitar and vocals of Gale’s younger sister Joann to his band and auxiliary chorus’ explosions of urgently swinging gospel fervor. As the lead track on Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music, it also sets the tone for one of the most unique albums within the storied Blue Note Records jazz catalog – a powerful merging of “out” and traditional elements that remains a restorative work of healing and a fierce celebration of Black identity.

Click to load video

Gale – a trumpeter, bandleader, and composer – was ideally suited to craft such a statement. Brooklyn born and bred, he counted Cub Scout marching bands and church choirs amongst his formative musical experiences. By the mid-’60s, his compact but potent resumé as a trumpet sideman reflected his affinity for post-bebop progressivism (appearing on terrific recordings by Sun Ra and organist Larry Young, and pianist Cecil Taylor’s ferocious avant-garde opus, Unit Structures). With a dual-bassist/drummer sextet line-up for Ghetto Music that literally doubles-down on the rhythm section as the engine of his sound, Gale organically interweaves recurring calls-and-responses between his trumpet, Russell Lyle’s tenor saxophone, and the Noble Gale Singers’ largely wordless ensemble vocals to animate vignettes of ghetto life from within. “Fulton Street” bustles with activity apropos to the titular thoroughfare that bisects historically Black Brooklyn, while the elegiac “A Understanding” moves with the gravitas of a memorial. Its main theme supported by a military marching band rhythm, “A Walk With Thee” pulses with the mobilizing energy of activism – instilled in Gale via his parents – with Gale and Lyle virtually soloing in the cadence of rally speakers.

Click to load video

Ghetto Music’s most explicitly personal composition, “The Coming of Gwilu,” is also its most epic, a 13-minute ceremonial song of praise exalting the birth of Eddie’ son. Once again commencing sparingly, this time with Lyle’s bird whistle/flute and Gale’s African thumb piano, its momentum is fueled by the soaring lead vocals of Elaine Beener over layers of bubbling percussion, including steel drum – an intoxicating mix as deep as Brooklyn’s own pan-African/Afro-Caribbean heritage. For Gale and his collaborators, within the emotive breadth of these colliding, polyrhythmic, nuanced sonic strokes there is, and must be, hope. Gale, who passed away in 2020 at age 78 after a lengthy career in music and education, in fact originally conceived Ghetto Music as a full-on dramatic theatrical production. In lieu of its realization, it’s to his enduring credit that his tour de force still retains all of its power as a historical score and salve.