Don’t Dictate: How DIY Punk Changed Music

Defiantly anti-establishment, punk’s DIY stance shocked the music industry in the 70s, but its influence can still be felt today – as uDiscover reveals.

After the UK’s premier punks, Sex Pistols, lambasted presenter Bill Grundy during their expletive-stuffed slot on Thames TV’s Today show in December 1976, the music industry received a short – but very sharp – shock.

The immediate fallout was far-reaching. With the press having a field day, Sex Pistols became household names overnight, and the term “punk” (previously of cult-level interest) suddenly gained widespread exposure. Petrified promoters duly cancelled most of Sex Pistols’ scheduled Anarchy UK tour dates, and, early in January ’77, a beleaguered EMI eventually dropped the band from their roster, reputedly paying £40,000 for the privilege.

The immediate fallout was far-reaching. With the press having a field day, Sex Pistols became household names overnight, and the term “punk” (previously of cult-level interest) suddenly gained widespread exposure. Petrified promoters duly cancelled most of Sex Pistols’ scheduled Anarchy UK tour dates, and, early in January ’77, a beleaguered EMI eventually dropped the band from their roster, reputedly paying £40,000 for the privilege.

Suddenly, punk appeared too hot to handle. Yet while this defiant new genre’s very existence apparently posed a threat to the music industry’s established status quo, it ultimately dissipated with a whimper, rather than a bang. Having eventually signed to Virgin Records, Sex Pistols split in disarray in January ’78; their nearest rivals, The Clash, set their sights on America; by the turn of the 80s, “punk” had been neutered and hijacked by hordes of identikit, Mohican-sporting Exploited clones.

However, one aspect of punk’s anti-establishment ideology endures to this day: its inherent DIY ethos, most often identified with the quintessential punk commandment: “This is a chord, this is another, this is another… now form a band!” Incorrectly attributed to Mark Perry’s seminal punk fanzine Sniffin’ Glue (the quote actually appeared, along with the relevant chord shapes, in the January ’77 edition of punk ’zine, Sideburns), this impassioned plea to create – and promote – music independently is always associated with 1976, yet there are pre-punk precedents. In North America, for example, Californian power-pop label Beserkley had been operating outside of the mainstream since 1973, while Cleveland’s avant-garde pioneers Pere Ubu released their landmark debut single ‘30 Seconds Over Tokyo’ on their own Hearthan label in 1975.

However, one aspect of punk’s anti-establishment ideology endures to this day: its inherent DIY ethos, most often identified with the quintessential punk commandment: “This is a chord, this is another, this is another… now form a band!” Incorrectly attributed to Mark Perry’s seminal punk fanzine Sniffin’ Glue (the quote actually appeared, along with the relevant chord shapes, in the January ’77 edition of punk ’zine, Sideburns), this impassioned plea to create – and promote – music independently is always associated with 1976, yet there are pre-punk precedents. In North America, for example, Californian power-pop label Beserkley had been operating outside of the mainstream since 1973, while Cleveland’s avant-garde pioneers Pere Ubu released their landmark debut single ‘30 Seconds Over Tokyo’ on their own Hearthan label in 1975.

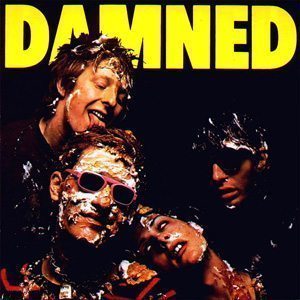

DIY, however, figured prominently in punk’s manifesto right from the start. Indeed, the UK’s first official “punk” 45, The Damned’s manic ‘New Rose’, appeared on the small (if upwardly mobile) independent imprint, Stiff Records, on 22 October 1976, beating Sex Pistols’ EMI-sponsored ‘Anarchy In The UK’ to the punch by five weeks.

The Damned also notched up another significant milestone on 18 February 1977, when Stiff issued their magnificently raw, Nick Lowe-produced debut album, Damned Damned Damned. The result of two frantic, cider- and speed-fuelled days at Islington’s tiny Pathway Studios, the record was rightly recognised as British punk’s first full-length LP, yet while Stiff were certainly independently minded, their two founding mavericks, Dave Robinson and future Elvis Costello manager Jake Riviera, were already well-known figures on London’s pub-rock circuit and their label was still broadly run from within the industry.

The Damned also notched up another significant milestone on 18 February 1977, when Stiff issued their magnificently raw, Nick Lowe-produced debut album, Damned Damned Damned. The result of two frantic, cider- and speed-fuelled days at Islington’s tiny Pathway Studios, the record was rightly recognised as British punk’s first full-length LP, yet while Stiff were certainly independently minded, their two founding mavericks, Dave Robinson and future Elvis Costello manager Jake Riviera, were already well-known figures on London’s pub-rock circuit and their label was still broadly run from within the industry.

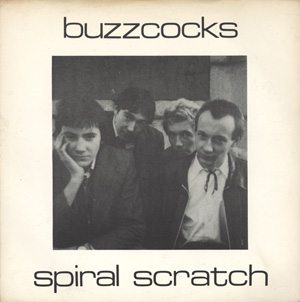

Not so the tiny New Hormones label, which was established specifically to release Mancunian punks Buzzcocks’ debut EP, Spiral Scratch, on 29 January 1977. Recorded and mixed in just five hours with future Joy Division producer Martin “Zero” Hannett at the controls, Spiral Scratch was entirely self-funded by the band (who borrowed around £500 to cover costs) and its release was a watershed in the history of independently released music: not least because it eventually sold out its original 1,000 pressing and then shifted a further 15,000 copies.

Arguably the most forward-thinking commercial outlet to sell Spiral Scratch was the Rough Trade shop, originally situated on London’s Kensington Park Road. Initially specialising in garage-rock and reggae, this remarkable operation, set up by founder Geoff Travis in February 1976 (and based upon San Francisco’s similarly “community-based” bookstore City Lights), stocked both Spiral Scratch and also May ’77’s Calling On Youth by Wimbledon trio The Outsiders. Though frequently overlooked in punk histories, this latter title was actually UK punk’s first truly independently issued LP, released through an imprint called Raw Edge, which had been set up by The Outsiders’ frontman Adrian Borland’s parents.

Arguably the most forward-thinking commercial outlet to sell Spiral Scratch was the Rough Trade shop, originally situated on London’s Kensington Park Road. Initially specialising in garage-rock and reggae, this remarkable operation, set up by founder Geoff Travis in February 1976 (and based upon San Francisco’s similarly “community-based” bookstore City Lights), stocked both Spiral Scratch and also May ’77’s Calling On Youth by Wimbledon trio The Outsiders. Though frequently overlooked in punk histories, this latter title was actually UK punk’s first truly independently issued LP, released through an imprint called Raw Edge, which had been set up by The Outsiders’ frontman Adrian Borland’s parents.

Suitably inspired, Rough Trade quickly established their own label, issuing their first 45, ‘Paris Maquis’, by French punks Metal Urbain, late in ’77. Taking a similar approach, a crop of newly established independent imprints then began to mushroom on both sides of the Atlantic.

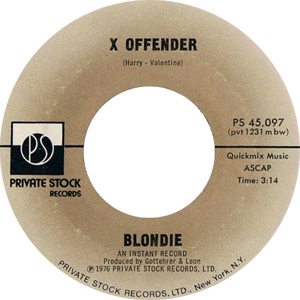

In the US, most of the essential NYC-based punk and proto-punks such as Ramones, Blondie, Television and Patti Smith signed with majors labels, but notable DIY labels, including the Akron, Ohio-based Clone, were simultaneously gaining ground in the Midwest, while in LA small but canny independent imprints, including Dangerhouse and What? (the latter responsible for the city’s first punk 7”, The Germs’ ‘Forming’) began to challenge the Hollywood hegemony during 1977 and ’78.

In the US, most of the essential NYC-based punk and proto-punks such as Ramones, Blondie, Television and Patti Smith signed with majors labels, but notable DIY labels, including the Akron, Ohio-based Clone, were simultaneously gaining ground in the Midwest, while in LA small but canny independent imprints, including Dangerhouse and What? (the latter responsible for the city’s first punk 7”, The Germs’ ‘Forming’) began to challenge the Hollywood hegemony during 1977 and ’78.

A similar pattern emerged in the UK, where Fulham-based record shop Beggars Banquet followed Rough Trade’s lead when they self-released West London punks The Lurkers’ first 45, ‘Shadow’, in July ’77. Over the next 18 months, the floodgates opened, with trailblazing provincial independent imprints such as Factory (Manchester), Zoo (Liverpool) and Edinburgh’s short-lived Fast Product joining the fray and releasing seminal early discs by now iconic punk and post-punk outfits including Joy Division, Teardrop Explodes and The Human League.

Rough Trade, however, took punk’s DIY self-sufficiency one step further during 1978 when they organised their own independent distribution network, dubbed “The Cartel”, which – through a series of like-minded UK shops – allowed them to sell their releases nationally. Many of these outlets also sold everything from self-released cassettes to fanzines and, in February 1979, Belfast punks Stiff Little Fingers’ incendiary, Rough Trade-sponsored debut, Inflammable Material, not only peaked at No.14 in the mainstream Top 40, but also became the first independently released LP to sell over 100,000 copies in the UK.

Rough Trade, however, took punk’s DIY self-sufficiency one step further during 1978 when they organised their own independent distribution network, dubbed “The Cartel”, which – through a series of like-minded UK shops – allowed them to sell their releases nationally. Many of these outlets also sold everything from self-released cassettes to fanzines and, in February 1979, Belfast punks Stiff Little Fingers’ incendiary, Rough Trade-sponsored debut, Inflammable Material, not only peaked at No.14 in the mainstream Top 40, but also became the first independently released LP to sell over 100,000 copies in the UK.

Such was the avalanche of independently released and distributed vinyl releases on the cusp of the 80s that the UK’s first weekly independent chart was published on 19 January 1980. That inaugural chart found Spizzenergi’s quirky, Rough Trade-sponsored ‘Where’s Captain Kirk?’ at No.1 in the singles listing and Adam & The Ants’ Dirk Wears White Sox topping the LP rundown.

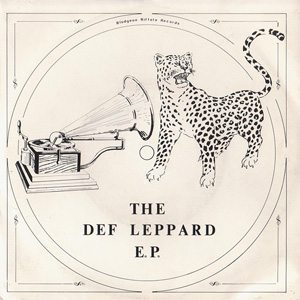

Other emerging genres of music also tapped into punk’s hardline DIY aesthetic. A whole new breed of British metal/hard rock bands had begun playing at grass-roots level parallel to punk, but their music was largely ignored by the press, save for Sounds’ hard rock correspondent Geoff Barton, whose review of a May 1979 London gig featuring Iron Maiden, Samson and Angel Witch appeared under the headline “New Wave Of British Heavy Metal”: a handy, catch-all term which eventually defined the entire movement.

Often abbreviated to the acronym “NWOBHM”, this highly competitive scene acted as the launch pad for future superstars Iron Maiden and Def Leppard, as well no less influential acts such as Diamond Head and Raven. Yet the music was initially built on punk’s DIY methodology of audio cassette demos, self-production and independently pressed singles released through small, hastily established labels, including Newcastle’s Neat imprint and Wolverhampton’s aptly titled Heavy Metal Records.

Often abbreviated to the acronym “NWOBHM”, this highly competitive scene acted as the launch pad for future superstars Iron Maiden and Def Leppard, as well no less influential acts such as Diamond Head and Raven. Yet the music was initially built on punk’s DIY methodology of audio cassette demos, self-production and independently pressed singles released through small, hastily established labels, including Newcastle’s Neat imprint and Wolverhampton’s aptly titled Heavy Metal Records.

Punk’s DIY aesthetic has since been detectable in much of the future-embracing music that’s been made over the past 35 years. This very self-sufficiency, for instance, was arguably the central tenet of fiercely independent imprints established during the 80s and 90s, among them anarcho-punk stronghold Crass and Washington, DC-based hardcore punk label Dischord, both of whom successfully produced all their own albums and sold them at discount prices without financial input from major distributors.

This same DIY passion was also a cornerstone of the best of the UK’s pre and post-C86 indie imprints such as Creation and Fire. Indeed, maverick Creation supremo Alan McGee’s punk-era education influenced virtually everything he did, from setting up his first London club night, The Living Room, through to the way his label marketed seismic, controversy-courting acts such as The Jesus & Mary Chain, Primal Scream and Oasis.

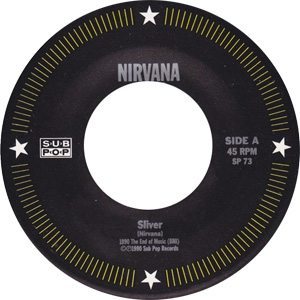

Elsewhere, landmark US independent labels such as Seattle’s Sub-Pop (initially the launch pad for grunge superstars Nirvana and Soundgarden) and Olympia’s K Records (one of the pioneers of the Riot Grrl movement) have openly confessed to the importance of punk’s DIY spirit to their development. Its handprint is also plain to see in histories of acid house, where the clandestine creativity required to set up the scene’s many (often illegal) all-nighters, such as the notorious Blackburn raves of the late 80s, is lifted straight from the pages of punk’s DIY manual.

Elsewhere, landmark US independent labels such as Seattle’s Sub-Pop (initially the launch pad for grunge superstars Nirvana and Soundgarden) and Olympia’s K Records (one of the pioneers of the Riot Grrl movement) have openly confessed to the importance of punk’s DIY spirit to their development. Its handprint is also plain to see in histories of acid house, where the clandestine creativity required to set up the scene’s many (often illegal) all-nighters, such as the notorious Blackburn raves of the late 80s, is lifted straight from the pages of punk’s DIY manual.

In the post-Y2K world, too, the DIY aesthetic is arguably more relevant than ever before. In 2007, Radiohead’s acclaimed In Rainbows made headline news around the world when the band released the album on a “pay what you want” basis via their website. With other global stars such as Nine Inch Nails (whose Ghosts I-IV was initially directly downloadable for just $5) since releasing records and circumventing the industry norm, it seems the pervasive DIY spirit of ’76 won’t go back into the bottle anytime soon.

Many of punk’s most notable DIY outings are featured on the compilation Punk: 40 Years Of Subversive Culture. Out now, it collects some of the landmark releases from punk’s upstart heroes, among them Buzzcocks’ ‘Time’s Up’, X-Ray Spex’s ‘Oh Bondage, Up Yours!’ and Blondie’s ‘Hanging On The Telephone’. You can purchase the compilation here:

Many of punk’s most notable DIY outings are featured on the compilation Punk: 40 Years Of Subversive Culture. Out now, it collects some of the landmark releases from punk’s upstart heroes, among them Buzzcocks’ ‘Time’s Up’, X-Ray Spex’s ‘Oh Bondage, Up Yours!’ and Blondie’s ‘Hanging On The Telephone’. You can purchase the compilation here: