Interview: Cyril And Emily Roussos On Aphrodite’s Child’s Masterpiece ‘666’

The children of the late great Demis Roussos discuss the prog masterpiece their father made with Vangelis as part of Aphrodite’s Child.

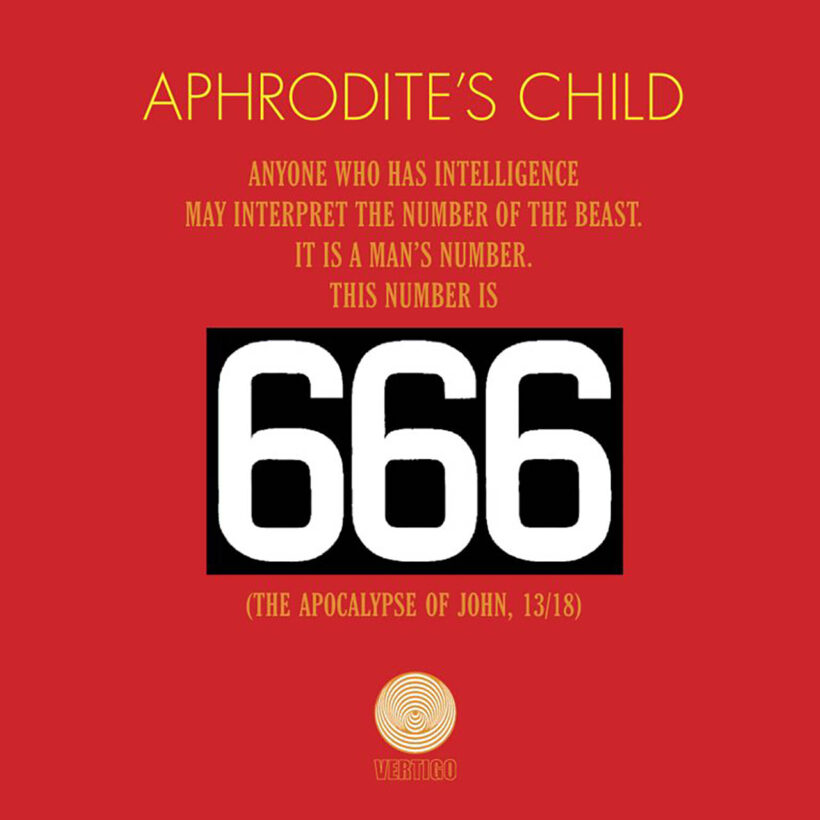

Released in 1972, 666 – The Apocalypse of John was the third and final album from Greek progressive rock greats Aphrodite’s Child. Formed in Athens in 1967 by Vangelis (keys, synths, flute), Demis Roussos (vocals, bass, guitar), Loukas Sideras (drums, vocals) and Silver Koulouris (guitar), the band decided to relocate the following year to escape the oppressive Regime of the Colonels, a right-wing Greek military junta that had taken control of the nation. It was a chaotic time across Europe. And complications with work permits meant that Aphrodite’s Child (minus Koulouris, who had been called up for national service) eventually made Paris, France, their home. Their second single, “Rain And Tears” was a massive hit all over Europe, selling over a million copies and their first two albums of psychedelic folk-pop and romantic ballads – End Of The World and It’s Five O’Clock established them as a force to be reckoned with. But nothing hinted at what was to come next.

Like Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys before him, Vangelis had quit the touring line-up of Aphrodite’s Child to concentrate on the studio and, along with outside lyricist Costas Ferris, started work on 666, an ambitious double concept album based on The Book Of Revelation, the final book of the New Testament. In late 1970, the band – restored to a four-piece after Koulouris’ return – entered the Europa Sonor studio in Paris to record Vangelis’ masterwork, a collection of anti-establishment songs that were heavier, wilder, and more experimental than anything they – or indeed, many other bands of the time – had previously attempted. Sessions took three months and cost the equivalent of $90,000. When the band’s label, Mercury, heard the tapes, they were surprised by the shift towards esoterica and heavy prog and took particular exception to the piece “∞”, which featured Greek actress Irene Papas moaning, seemingly in the throes of sexual ecstasy.

Order 666 – The Apocalypse Of John.

Mercury asked Vangelis to edit the album and he refused, resulting in a stand-off that lasted until June 1972, when 666 was finally released on the label’s prog offshoot, Vertigo. Since then, 666 has become recognized as one of the visionary rock albums of the early 1970s and launched the hugely successful solo careers of both Vangelis and Roussos.

A new super deluxe edition of the album features a full remaster of the original album, the rare 1974 Greek mix and a Blu-ray disc featuring a 96 kHz / 24-bit Atmos and 5.1 up mixes and stereo mix, all of which were overseen by Vangelis before his passing in 2022. We spoke to Demis Rossos’ children, Emily and Cyril – both of whom are musicians in their own right – about the box set, their father’s memories of his time in Aphrodite’s Child, and how much the music he made with Vangelis meant to him.

It must be an amazing experience to see this deluxe package come together, from the remastering of the album to uncovering previously unseen photographs of your father…

Emily Roussos: It’s been very emotional for both of us. Obviously, it would also have been emotional for our father because we know how much his work with Vangelis meant to him and how grateful he was for their relationship throughout his life. He said in the film I did with him [Journey With My Father] how much Vangelis had contributed to making his voice heard throughout the world. The work they did together in Aphrodite’s Child before getting back together in the early 1980s in London for the Blade Runner soundtrack was very, very important for him.

Cyril Roussos: What I think is significant is the fact that this is such an important album – it needs to be heard. If for no other reason than just to understand and experience what music can be when it’s conceptual and executed with surgical precision. The way that only Vangelis can put something together and present it. It’s a sensational feeling for me to see this album come back, and hopefully be discovered – by younger people perhaps, or somebody who never had a chance to hear it before who can say, ‘Oh yeah, I always wanted to check that out and now I can.’ That’s definitely cool, but what’s more important is that it is being recognized for what it is, which is one of the most seminal and greatest progressive rock albums ever put together.

Was this an album that you heard from an early age?

ER: Oh yes, of course, I heard it in my mother’s house and it was always part of our lives.

CR: I discovered 666 at the best possible time you can – years later as a teenager. I had long hair and spent most of my time in my room listening to The Dark Side of the Moon, 666 – these types of things. I just couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Man, it blew my little mind away! I actually remember going up to my father after hearing it for the first time, and saying, “Jesus Christ, you did this?!” Obviously, he laughed, he had a great sense of humor.

Even at that young age, I was so taken aback at the almost cinematic exploration the album took. I didn’t really understand what concept albums were at the time – sure, I would have heard them, but I certainly didn’t appreciate them in the way that I do today. But when I heard this, I was taken aback, I really remember the experience. It’s certainly not an album that you can just play one song from, you’ve got to hear the album entirely. And every time I’m blown away by it, by the detail of it.

Why do you think there was such a radical change from their early albums in terms of the sound and ambition?

ER: Vangelis was the creator of something that he had something very deep inside him, and wanted to do for years. So he had the artists around him that he believed in the most and Demis – obviously, since the beginning – was part of that, along with Loukas Sideras, Silver Koulouris, Irini Papas and many other artists. He wanted them to be part of that huge and important journey for him. So he was the beginner and the creator of that journey.

CR: Ultimately, they made 666 because they could. They had released pop-type albums with mainstream songs that could be played on the radio, which was a big deal, and they had established themselves well enough to be able to get away with, ‘Hey, you know what? We got this idea for an album.’ It was also a time when you could do that, they were given freedom to make whatever album they wanted. And they really took that to heart. We Greeks tend to be a little bit absurdist, whether it’s Yorgos Lanthimos films or whatever. I suppose that goes back to our ancient culture of creating myths, which, if you take at face value, are very absurd, but are just meant to be used as metaphors.

In the book that accompanies the set there’s an old interview in which Demis says, “When I was a child, I sang in churches. That’s why I totally feel this music, I can do it better than anyone.” How did them being exiles from Greece influence the music?

CR: There’s the culture of orthodoxy here in Greece, which used to be much more prevalent. The Byzantine sound of that religious music must have really influenced Vangelis and certainly influenced our father. He was very fortunate, because he grew up in Egypt, so he would hear the Byzantine music in the Orthodox Church, but he would also hear the Muslims on the other side every morning doing Amman prayers. That blend gave 666 a unique sound and perspective that could only come from Greek immigrants.

ER: We must not forget that these guys arrived from a Greece run by the Colonels. My father told me stories about him running along the streets followed by a Colonel or a cop who wanted to cut his long hair. They were not allowed to even sing in English. They escaped all of this when they moved to Paris. So this album is also a shout against that by artists who just wanted to be and create.

I think 666 is what the four of them had inside them as artists and is a reaction to the political condition of Greece at that moment, and what they escaped from. Vangelis probably wanted to end Aphrodite’s Child’s journey with the project that he had very deep inside, like a film director who is going to, at last, make the film that he’s had inside him for so long. Maybe it will be produced with more difficulties, because it’s less mainstream, but it’s going to be what he really has to say.

CR: I also think it was a bunch of very young, God bless them, very crazy young artists in what was undoubtedly the greatest era to be in rock’n’roll, going out of their way to create art through music. Also, I think that they knew that they were coming near the end, and it was like, ‘Hey, let’s go out with a bang’. That is such a young person’s mentality. When you’re older, you’re a bit more reserved, but when you’re young, you take those risks, and boy, did it pay off.

The sessions certainly look enjoyable from the photographs included in the box set. Your father has a huge smile on his face in so many of them…

ER: I think he was happy doing that type of music. He even said to me, a little time before he passed away, that Vangelis was one of the two musicians who actually heard his voice and knew how to write for him – along with Jeff Picci who he worked with on his last album, Demis, in 2009. So obviously, this very long and deep experience that was this album, which went on for months and months, I think it was very nourishing for both of them. Demis was truthfully a sunny person inside. He was a positive person. The smile you see in the photographs you’re talking about is a true smile.

CR: He certainly must have enjoyed himself on this album. My God, listen to “The Four Horsemen”. There are no limits to what he’s doing with his voice, there’s no actual control – just go free, go out, give me more. How rewarding that feels as a musical artist, when you’re not limited to, ‘Keep it in time. We want to keep it tight.’ You’re not being constricted. You can just be free to express yourself completely and entirely. Wow, what a wonderful emotion, what a wonderful feeling. This isn’t the type of work where, if it feels like work, it’s going well. No, if it feels like fun, then it’s going well. It needs to be like that because that’s what keeps those creative doors open. That’s what allows you to give 100%.

One of the stranger stories around 666 is the interest that Salvador Dali took in the album and the ‘happening’ that he hoped to stage around the release. Did your father have much to do with Dali?

ER: Our father used to tell us that Dali loved Aphrodite’s Child, and that he would arrive at all the concerts with a cabinet toilet that he would carry with him and sit on the cabinet for the concert.

That’s one way of avoiding queues. And how did your father feel about 666 being embraced by a younger generation?

CR: Oh, he was very proud. I’m around musicians all the time and the conversation is always, at some point, going to lean towards 666. It’s left such a mark on musicians, especially Greek rock musicians. It’s part of their skin now, their tattoos for life.

During his 2002 UK tour we were somewhere up north, I think it was in Scotland, and there were these kids in the audience. They couldn’t have been more than 20. It was such a surreal thing to see, because when you looked at the average Demis audience, they were of a certain age group. And in the middle of that, here are these three young guys in black with long hair, torn jeans, sticking out like a sore thumb. They walked up to my father after the show and just wanted to talk to him about 666, acting as if they had a God before them. From what I understood later on, they were a band themselves. I remember the glow that came out of Dennis, his smile lasted all freaking night long. He absolutely loved that this thing was still out there, circulating and being appreciated the way it was, especially by young people. He was very, very proud of that.

And do you each have favorite moments on 666?

ER: “The Four Horsemen”, definitely. I’ve been listening to it quite a lot again lately and it’s interesting – like with any piece of art actually, whether it’s a painting, a sculpture, or a film or music – when the more you hear it, the more you actually like it. And it’s totally another type of song but I like “Break” as well, I find it very beautiful.

CR: The remastering is amazing. The job they did is just phenomenal. They took very, very close care here to make sure that everything that was meant to stand out is heard. It’s almost like listening to a different album for someone like me, who has heard it so many times over the years. I had always heard details like, ‘Oh, there’s that little bell’, but now it’s clear. And it has a personality, and it changes your perception of the music enough to have a much wider vision for it. This is how you remaster an album.

But I do not have a favorite track, and I’ll tell you why – this is a concept album. It’s gotta be heard in its entirety man! This is a put it on, light it up, and wait till the end fricking experience! I mean, sure, there are probably things that stick out more and I certainly do like the songs that my sister mentioned. I also think “Babylon” is, you know, quite the slapper. But it’s meant to be seen as a whole. It’s meant to be experienced as a whole, and now it does that better than ever.