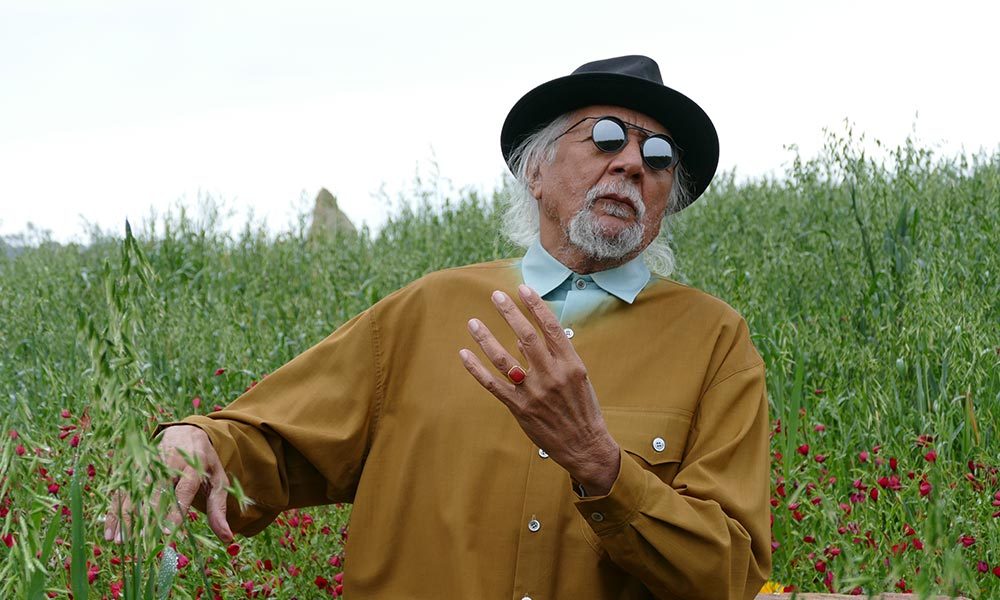

‘Vanished Gardens’ “Jumps Conventional Boundaries” Says Charles Lloyd

For ‘Vanished Gardens’, Charles Lloyd added Lucinda Williams to his acclaimed group The Marvels, resulting in an album for which “there is no precedent”.

“The recording is definitely a cross-pollination of different worlds,” says Charles Lloyd, reflecting on the unclassifiable but eminently accessible musical terrain of his fourth Blue Note album, Vanished Gardens, where jazz improv, blues, gospel and Americana are inextricably intertwined. “It’s not easy to give what we are doing a category,” he says, “but if it’s great, it doesn’t matter what genre it is identified by. Labels can be so misleading, anyway.”

Listen to Vanished Gardens right now.

Vanished Gardens is the 80-year-old saxophonist/flautist’s second album with The Marvels, a supergroup whose ranks feature noted guitar maestro Bill Frisell, a fretboard virtuoso long renowned for his musical shape-shifting. He’s joined by country-influenced pedal steel and dobro expert Greg Leisz, alongside a jazz rhythm section comprised of bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Eric Harland. It’s an unusual, multicultural and multi-genre mesh of talents but, as the group’s debut album, 2016’s I Long To See You, convincingly demonstrated, they sound like they’ve been playing together for years.

What’s different this time around is the presence of triple-Grammy-winning folk troubadour Lucinda Williams, whose weathered, smoky vocals grace five of Vanished Gardens’ ten tracks. “After we released I Long To See You, Lucinda came to one of our Marvels concerts in Santa Barbara,” says Lloyd, recalling how the singer-songwriter came on board. “She, Bill and Greg had known and worked together on several projects spanning a couple of decades. I knew of her from Car Wheels On A Gravel Road (her Grammy-winning album from 1999) and loved what she does. Following that meeting, she invited me to guest at her concert at UCLA a few months later, and I invited her to guest at one of my concerts. We then decided we should go into the studio to document what we were doing.”

“I don’t think there is a precedent for this recording”

The end result is a magical convergence of talents from different musical worlds: six musicians from diverse backgrounds who create alchemy together and take the listener on a journey into a new and hitherto undiscovered sonic landscape. “I don’t think there is a precedent for this recording,” says Lloyd. “Lucinda and I jumped into a river of music flowing toward the unknown. We found that the river widened with all of us in there: Lu, me, Bill, Greg, Reuben and Eric… all swimming in the same direction, but not necessarily the same stroke.”

“All swimming in the same direction, but not necessarily the same stroke.” From left to right: Greg Leisz, Lucinda Williams, Charles Lloyd, Eric Harland, Reuben Rogers, Bill Frissel. Photo: D Darr

They achieved a rare sense of musical communion on Vanished Gardens without sacrificing what makes them unique as musicians, which the veteran saxophonist is keen to emphasise. “Lucinda was not turning into a jazz singer and we were not transforming our approach to become country/Americana musicians,” he says.

Williams contributes four original songs to Vanished Gardens, all gems. Though pensive, they are deeply passionate explorations of the human psyche. ‘Dust’ is a solemn existential meditation, while ‘Ventura’, though lighter in tone, is a wry confessional in which the mundanity of life is juxtaposed with the elemental beauty of nature. Lloyd plays an eloquent, unaccompanied saxophone solo to introduce the slow, waltz-time ballad ‘We’ve Gone Too Far To Turn Around’, an anthem of perseverance in the face of adversity. The energetic ‘Unsuffer Me’ is more overtly optimistic, about finding redemption through love. “Lu is a great poet,” says Lloyd, eulogising the Louisiana-born singer-songwriter’s gift for marrying words and music. “Her imagery is visceral and visual – unexpected reflections into human emotions.”

The fifth Vanished Gardens song to feature Williams’ voice is the album’s closer, a unique take on Jimi Hendrix’s much-covered ballad ‘Angel’. “This was a song that Lucinda had picked out to sing,” explains Lloyd. “The session was over, everyone had left the studio except for Bill and me. She said, ‘I wish we had been able to record “Angel.”’ Bill and I agreed to give it a shot and we did it in one take.” Though extemporised at the last minute, the combination of Williams’ plaintive voice with Lloyd’s fluttering saxophone notes and Frisell’s skeletal guitar filigrees is magical. For Lloyd, the song also brings back vivid memories of his friendship with the song’s composer. “Jimi and I knew each other from our days in Greenwich Village,” he reveals. “We had spoken of doing something together, but time ran out.”

“The utopia of our dreams”

Central to The Marvels’ sound is Bill Frisell’s distinctive guitar, which is subtle and often understated but also powerfully magnetic. The 67-year-old Maryland musician plays in an eclectic yet singular style that references jazz and bebop but is also steeped in folk and Americana. “Bill is a wonder,” says Lloyd. “He is one of the most versatile and expansive musicians I know. He brings humour and depth to whatever he does. We have a deep simpatico on and off the stage.”

Frisell’s guitar, with its spidery, staccato notes, is a key component of the title song to Vanished Gardens: a meandering meditation on loss which ebbs and flows and whose title is an elegiac metaphor for the current state of the world. Lloyd, its composer, says, “‘Vanished Gardens’ refers to the utopia of our dreams, a garden of Eden, which, in the current political climate, is being eroded away like a garden with no attention to erosion control.”

The most jazz-influenced track on Vanished Gardens is an absorbing version of Thelonious Monk’s classic composition ‘Monk’s Mood’, which is reconfigured as a duo for Lloyd’s tenor saxophone and Frisell’s guitar. “Monk is the great architect of our music,” says Lloyd, who knew the idiosyncratic composer/pianist very well. “We used to play opposite each other at the Village Vanguard.”

Indelibly engraved in Lloyd’s mind is a curious incident that happened backstage at the Vanguard when he was on the same bill as Monk in the 60s. It still makes him smile and encapsulates both the mischievous and rebellious side of Monk’s personality. “I had a requirement on my rider that every night I had to have fresh orange juice in the dressing room which Monk and I shared,” recalls Lloyd. “He always had a glass when he came in each night, but one night the juice was not fresh, so when the Baroness [Pannonica de Koenigswarter, Monk’s patron] came in, I told her to ‘please tell Monk not to drink the juice tonight because it’s tainted.’” On Monk’s arrival, the Baroness warned him that the orange juice was off but that didn’t deter the pianist, who, according to Lloyd, “danced his way around the room to the pitcher of juice and picked it up”. What happened next stunned the saxophonist. “He then danced his way back to me, and while staring me in the eyes, drank the whole thing down. He said, ‘Tainted, huh?’ and danced off.” Lloyd still laughs at the recollection, which, he says, “reminded me of the Tibetan monk, Milarepa, who took poison and turned it into soma”.

“Rock groups wanted to be on our bill… we were opening the music up so much”

Like Thelonious Monk, Charles Lloyd is regarded as a mystical figure in jazz. He famously retreated from the music scene at the end of the 60s to live an ascetic, solitary life in Big Sur, California, and it was there that he immersed himself in the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment for many years. “My candle was burning from both ends and was about to meet in the middle,” the saxophonist admits; he says he stepped away from the jazz world in a bid for self-preservation and to heal himself.

His career, though, had begun so spectacularly. Originally from Memphis, Tennessee, Lloyd began playing the saxophone when he was nine, though the musician that had the most profound impact on him, he says, was a pianist, Phineas Newborn. “He was my earliest influence and mentor,” reveals Lloyd. “His affect has been lifelong. I attribute the seed he planted in me for being responsible for all of the great pianists I have worked with.”

In 1956, Lloyd left Bluff City for Los Angeles, and, in 1960, he joined drummer Chico Hamilton’s groundbreaking quintet, replacing the estimable Eric Dolphy. “[Saxophonist] Buddy Collette was responsible for that,” says Lloyd. “After I graduated from USC, I was teaching in LA. Buddy knew that I wanted to play, so when Eric left he called Chico and said, ‘I have just the right sax player for you.’ It was a great learning experience, especially after he made me music director. I was able to bring [guitarist] Gabor Szabo and [bassist] Albert Stenson to the band. It was a dream team for a while.”

Lloyd then joined Cannonball Adderley’s band before leaving, in 1965, to lead his own quartet with pianist Keith Jarrett, bassist Cecil McBee and drummer Jack DeJohnette. “We all loved exploring the unknown,” says Lloyd of a group that liked to travel to “far-out” musical destinations and yet still made accessible music. “We were young idealists and the timing was right for us to come together.”

The quartet became the darlings of the American counterculture scene in the late 60s and were the first jazz group to play alongside rock and blues acts at promoter Bill Graham’s legendary Fillmore West venue. “A San Francisco group called The Committee used to come hear me play,” says Lloyd, recalling how his quartet registered on Bill Graham’s radar. “They told me I should be playing at a place called The Fillmore where there were a lot of young people. When I asked who else played there they said Muddy Waters. I knew him so I said OK, and then Bill Graham booked me one afternoon for half an hour.”

The quartet went down so well with the hippies that they weren’t allowed to leave. “The audience kept us on stage for over an hour,” remembers Lloyd. “After that, the rock groups wanted to be on the bill with us because we were opening the music up so much and they wanted that experience, too.”

Firing arrows into infinity

After the highs of the late 60s, Lloyd, by his own admission, was burned out. The 70s found the saxophonist in a meditative frame of mind and, though he still recorded intermittently, the records he made were more New Age in style than jazz. That all changed in 1986, when, according to the saxophonist, “I nearly died.” Struck down with a serious intestinal disorder, he had to undergo emergency surgery. Understandably, the experience changed him and made him take stock of his life. “When I recovered, I decided to rededicate myself to this music called jazz,” says Lloyd. “I had been gone for so long they made me get at the back of the line. It was a long, slow, re-entry.”

But Charles Lloyd is nothing if not persistent. By dint of hard work and dedication to his art, he’s built up a large and impressive body of work during the last 30 years, ensuring that he’s now at the front of the line and rightly revered as a jazz elder. Though he turned 80 in March 2018, Vanished Gardens shows that his desire to create new music – what he calls “firing arrows into infinity” – is stronger than ever.

![Charles Lloyd And The Marvels with Lucinda Williams Vanished Gardens [02] web optimised 740](https://www.udiscovermusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/CharlesLloydTheMarvelsLucindaWilliams_2_byD-web-optimised-740.jpg)

Photo: D Darr

His closing concert at Newport, on Sunday, 5 August, is billed as Charles Lloyd And Friends With Lucinda Williams. Though Bill Frisell can’t make the gig, Williams’ presence means that the saxophone magus will play some of the material from Vanished Gardens, an album that articulates his desire to make music that, he says, “jumps boundaries of conventional labels”.

Vanished Gardens is out now and can be bought here.