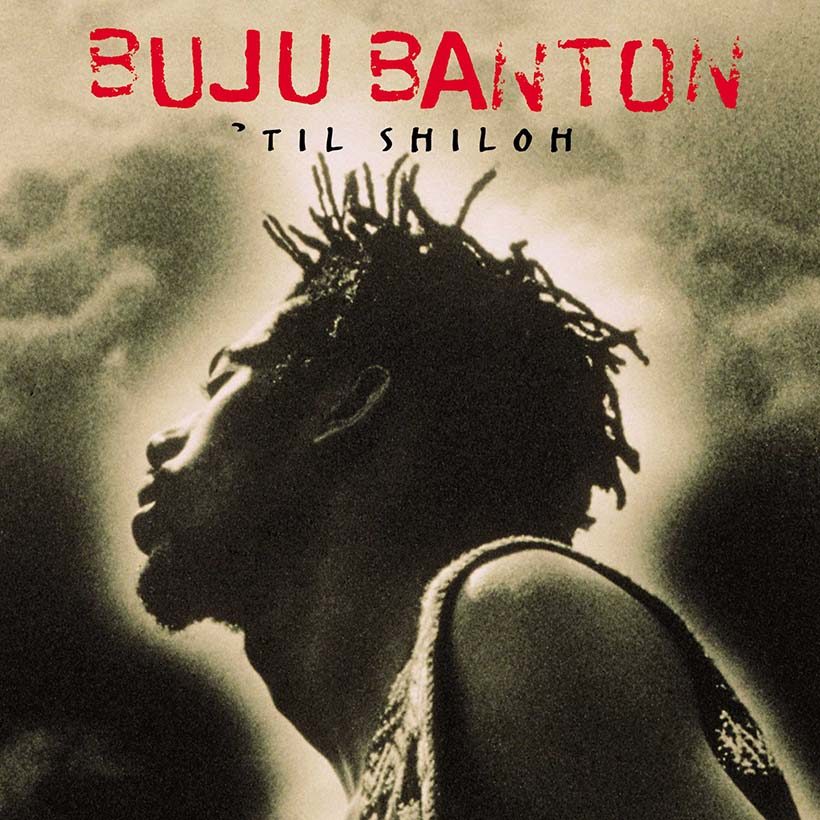

‘Til Shiloh’: Buju Banton’s Groundbreaking Album

It was an album that changed the trajectory of the dancehall artist’s career… and also transformed dancehall and reggae forever.

One cannot discuss the history of Jamaican music without Buju Banton. Born Mark Anthony Myrie, he grew from a lanky teen studying local Kingston deejays to an artist that propelled dancehall and reggae to international heights.

Banton emerged in 1987, and quickly became a leader in dancehall – a genre in its infancy in Jamaica. With albums like 1992’s Mr. Mention and 1993’s Voice of Jamaica, Banton created a “rude bwoy” persona laced with a raspy vocal tone and streetwise lyricism. By 1995, however, Banton was in search of something much bigger. He was in the process of converting to Rastafarianism. He began growing out his locs, studying the words of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I, and spiritually cleansed the hard edges that surrounded his previous music. The musical result? A melodic Rasta reggae classic called ‘Til Shiloh.

Listen to Buju Banton’s ‘Til Shiloh now.

With the assistance of local producers Donovan Germain, Lisa Cortes Bobby ‘Digital’ Dixon, Dave Kelly, Sylvester Gorton, and Steely & Clevie, Banton transformed the sound of dancehall with ‘Til Shiloh. As the genre entered the 90s, technology began to replace live recording. ‘Til Shiloh was a bridge: it combined digital programming with roots reggae-inspired instrumentation (like acoustic guitars and Nyabinghi drums specifically used by the Rastafari community) that calls back to the motherland that Banton was longing for. Crucially, it allowed for many to see that dancehall needn’t remain reggae’s rowdy, younger kin. ‘Til Shiloh proved that dancehall was an adaptable sound that could live in harmony with reggae.

The album was a moment of maturity for Banton, whose road to consciousness found him with a newfound sense of ancestral pride. During this time, Banton learned about his Maroon lineage that traces all the way back to 18th-century runaway slaves. And on ‘Til Shiloh, Banton combines social commentary while simultaneously blurring the lines between dancehall’s party-driven slackness and the political upheaval that anchored reggae music. You can hear it from the first track, “‘Till I’m Laid To Rest.” With straightforward production of an African choir and commanding percussion, Banton is weighed down by Western colonization. “I’m in bondage living is a mess/I’ve got to rise up and alleviate the stress,” he sings in a pained voice. “No longer will I expose my weakness.”

Banton’s spiritual awakening further distanced himself from the days of “Boom Bye Bye.” The single, recorded at age 16, caused enormous controversy over its lyrics. ‘Til Shiloh was a necessary rebirth that put him on a similar path to Bob Marley. And, like the reggae icon, Banton saw part of his mission as an educational one. For decades, Rastas were rejected from mainstream society due to their pan-African beliefs and heavy weed smoking. Bob Marley’s prominence went some way toward changing the perception of Rastas. But, as Banton put it in 2020 to The Guardian, there was still a long way to go. “We have shared our music with the world and we see many people wearing dreads, but they don’t understand the teachings.”

One of the most compelling moments of ‘Til Shiloh is “Untold Stories,” where Banton channels Marley’s spirit. Banton’s softer vocal is beautifully highlighted by the acoustic guitar. “It’s a competitive world for low budget people,” he intones, “spending a dime while earning a nickel.” Songs like “Complaint,” meanwhile, take aim at those that seek to keep those low budget people down. “Children arise from your sleep and slumber/Don’t come to bow, come to conquer,” Banton stresses in the first chorus. “Murderer” is a direct callout to Jamaica’s alleged corrupt government. A response to the murders of friends and fellow artists Panhead and Dirtsman, the song captures Banton’s anger with the gunmen who got away scot-free and the system’s mishandling of the island’s gun violence.

Along with the more serious tunes, there are glimpses of cheeky dancehall with “Only Man” on the Arab Attack riddim and the Steely & Clevie-produced “It’s All Over.” In a call back to Banton’s early Romeo days, “Wanna Be Loved” showed that Rastas could flirt just as passionately as they prayed to Jah.

Buju Banton’s Til Shiloh was a fearless record that laid a foundation for dancehall artists. Following its release, Capelton, Sizzla, Anthony B, Beenie Man, and more soon folded Rastafari beliefs into their own music. Today, a new generation of dancehall artists like Koffee, Chronixx, Chronic Law, Leno Banton, and Protoje are doing the same. ‘Til Shiloh remains a manifesto for those looking to explore the Rastafari faith and become closer to their ancestry. The album is named after a Jamaican saying that means “forever,” which is exactly how long Banton is hoping its impact will last.

Buju Banton’s ‘Til Shiloh has been re-released upon its 25th anniversary with plenty of extras. Listen to the album here.