Best Brian Eno Songs: 20 Essential Tracks

If Brian Eno’s name appears anywhere in an album’s credits, enlightened listeners will sit forward. uDiscover introduces the best Brian Eno songs.

It may seem delusional to presume that a figure of Brian Eno’s artistic heft could be adequately summarized in 20 songs. However, one of Eno’s most enviable accomplishments is to have become synonymous with the dissemination of inspiring, provocative, avant-garde ideas, bringing a playfully unfettered art sensibility to pop and rock music. If his name appears anywhere in an album’s credits, enlightened listeners will sit forward; the best Brian Eno songs remain visionary, thought-provoking and still signpost the future.

Listen to the best of Brian Eno on Apple Music and Spotify.

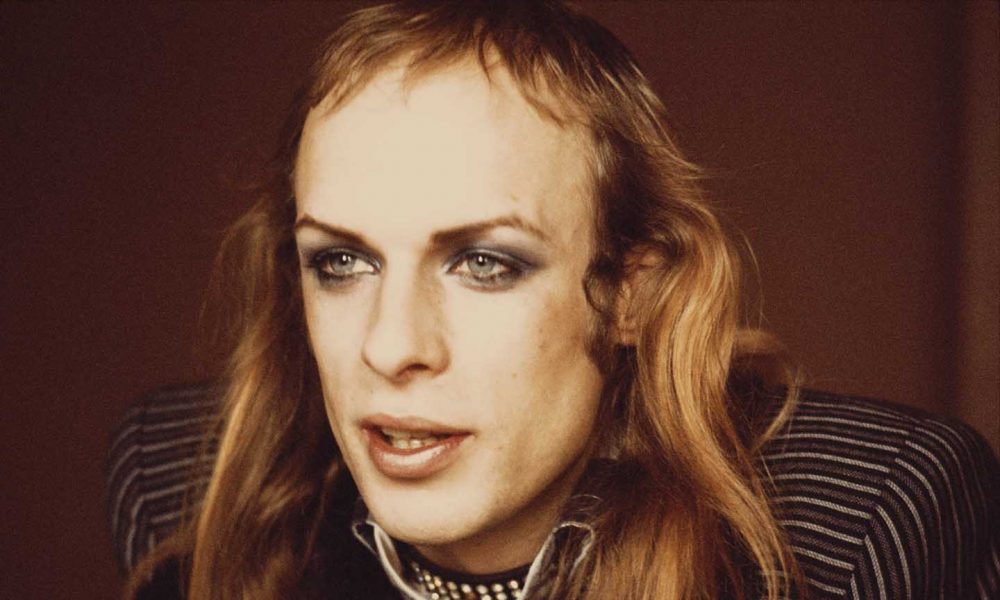

Most of us first encountered the erstwhile art student, born on 15 May 1948, when Roxy Music’s “Virginia Plain” strutted, jaw-droppingly, into the charts in the summer of 1972. It wasn’t so much that Roxy looked and sounded like they came from nowhere; more that they seemed to have evolved on a parallel earth that was somehow infinitely sexier, artier and more trashily magical than our damp and destitute domain. The blithely and defiantly non-musical Eno was tasked to lob glittery spanners into his bandmates’ path, destabilising an early VCS3 synth and getting right up musos’ flared nostrils: but a fork in the road wasn’t far away.

Eno and Roxy vocalist Bryan Ferry ultimately succumbed to time-honoured “artistic differences”; however, they proved a productive match while they were briefly on the same page: note the gibbering overlay which Eno smears onto “Re-make/Re-model” from the self-titled 1972 Roxy debut album, and Eno’s striking synth anti-solo on “Editions Of You” from the following year’s For Your Pleasure.

For someone who claimed no interest in the processes of stardom – and difficult as it is to reconcile the young peacock hedonist with the professorial polymath of later years – Eno would have made a terrific pop star, if only his perversely experimental soul had allowed it. His debut solo album, 1973’s Here Come The Warm Jets, contains several little pockets of raised-eyebrow avant-glam – but, tellingly, the tense and minimal “Baby’s On Fire,” one of the best Brian Eno songs from this period, comes with a haywire guitar solo that simultaneously exalts and parodies rock excess. Meanwhile, “Dead Finks Don’t Talk” appeared to be directed at his former bandmate.

Yet Eno had already outgrown all of this even as he was creating it, and, by the mid-70s, was aligning himself (and collaborating with) like-minded iconoclasts including redoubtable guitarist Robert Fripp of King Crimson, and the discreetly resolute German gentlemen who comprised the Cluster/Harmonia axis, namely Hans-Joachim Roedelius, Dieter Moebius and Michael Rother. Given that this characteristic kink in Eno’s career path signposted a desire to disengage from orthodoxy and mainstream acceptability, it’s of no little significance that the simple, elegiac, heart-tugging title track of 1975’s Another Green World should nevertheless end up encoded in the DNA of a generation as the evocative theme for the BBC’s long-running Arena programme.

Besotted with Cluster’s opaque, self-contained ethos, Eno travelled to Lower Saxony to meet and record with them – and their influence resonates all over the contemplative second side of 1977’s Before And After Science (Roedelius and Moebius themselves appear on the weightless still-life, “By This River”). Also well ahead of the curve in identifying and drawing upon Germany’s most fresh and least conventional rock music was David Bowie – as reflected in the exploratory boldness of his nominal “Berlin trilogy”: 1977’s Low and “Heroes”, and 1979’s Lodger. Eno was a key collaborator in this phase of Bowie’s career, his working methods combining serious intent with a liberating pursuance of happenstance. To this end, Eno had already devised a set of Oblique Strategies cards with artist Peter Schmidt, designed to overcome artistic stumbling blocks with phrases that stimulated new avenues of thought.

The consequent upending of procedures engendered an atmosphere of freely indulged (but never indulgent) ideas and initiatives. Between them, Bowie, Eno and co-producer Tony Visconti created a sonic context in which abstruse textures and abstract decisions contributed towards an overall lucidity. This resulted in some of Bowie’s most starkly beautiful work, not least Low’s dignified, emotive “Warszawa,” which Bowie intermittently used as a palliative concert opener, and “Moss Garden” from “Heroes”, with Bowie playing a Japanese koto. Lodger, meanwhile, includes the stomping, swaggering “Boys Keep Swinging,” a magnificently blowsy endeavour in which Bowie’s band were encouraged to swap instruments – the very definition of an obliquely strategic manoeuvre.

Yet while Eno’s production profile grew, not everyone took to the deployment of Oblique Strategies cards. Devo reportedly bridled at the prospect when Eno manned the board for 1978’s Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! – while, for his part, Eno felt creatively constrained by Devo’s reluctance to deviate from their original demos. Nevertheless, the band were impressed by Eno’s ability to seamlessly interweave a tape of “Balinese monkey chanters” into the startling “Jocko Homo.”

A more harmonious alliance was forged with Talking Heads – particularly on 1979’s unimpeachable Fear Of Music, in which Eno’s electronic treatments imparted a chilly frisson to the mixes. (To this writer’s ears, “Mind,” “Electric Guitar,” and “Drugs” still sound like the future.) Eno and Heads frontman David Byrne went on to release 1981’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, influentially implementing “found sounds” and samples as central components of the tracks (as in the turbulent “America Is Waiting”).

Concurrent with his comparatively high-profile production work, Eno had been pursuing a keen interest in ambient music – his term – for a number of years. The diffident, neutral soundscapes contained on albums such as 1978’s Ambient 1: Music For Airports were deliberately pitched so as to function on several levels: to reflect back the listener’s mood; to be as absorbing or subliminal as circumstances dictated. And sometimes, as with “An Ending (Ascent),” from 1982’s Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks, Eno captured something so ethereal and emotionally affecting that it seemed to be nothing less than music from the heavens.

In more recent years, Eno consolidated a long-running and rewardingly successful co-production role with U2 by fulfilling a similarly lucrative function for Coldplay. “One,” from U2’s 1991 album Achtung Baby (co-produced with Daniel Lanois), is a fittingly prime example of his unrivalled ability to constructively deconstruct a song, stripping away a thicket of overdubs to locate the fundamental meaning. Eno can also be credited with bringing a distinct Velvet Underground influence to bear on “Yes,” from Coldplay’s 2008 album Viva La Vida Or Death And All His Friends.

It’s tempting to surmise that, for all his creative wanderlust, Eno might not be averse to fondly raking over familiar ground. 2010’s Small Craft On A Milk Sea, recorded in collaboration with soundtrack supremos Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams, channelled ambient traces (“Calcium Needles”) with a subtly thematic thread; 2014’s Someday World, conceived with Karl Hyde of Underworld, wryly sported some distinctly 80s resonances (“Daddy’s Car”).

Meanwhile, Music For Installations scours three decades’ worth of Eno’s audio-visual experiments, presenting a collection of pieces recorded specifically for installations. “Kazakhstan” was created for the UK Pavilion at the Astana Expo 2017, held in Kazakhstan. The installation was a collaboration with architect Asif Kahn, and the track is a perfectly haunting piece of music.

The super deluxe 6CD Music For Installations box set can be bought here.

Garyously

December 2, 2016 at 5:31 pm

The song missing 4 me would be This from Another Day On Earth…

JimmyD

September 15, 2017 at 8:19 pm

No Spider and I? Oh dear…

peter f shelley

June 10, 2018 at 6:05 pm

What.. you don’t have “An Ending Ascent” you don’t know eno then. This is his #1 song..and may i say it being in a variety of movies..

ending for Traffic; 28 days; apollo only adds to it’s weight.

Kevin Grace

July 4, 2020 at 1:29 pm

First… you got his birth date wrong….

and to not mention “Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)?

Spend a little more money on people

who know what they’re talking about.

Jeeze…

Be safe.

Peace on earth…

Danny Smalle

October 6, 2022 at 7:33 am

Born in 1948, not 1958…

Todd Burns

October 11, 2022 at 10:02 pm

Thanks for the correction! We’ve fixed that now.