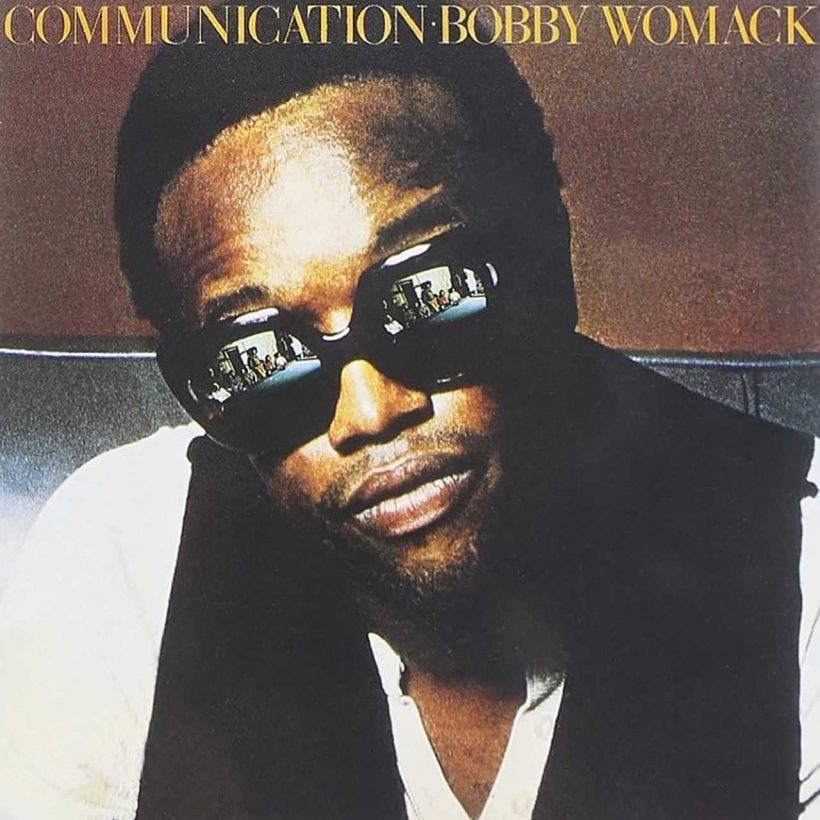

‘Communication’: Bobby Womack Balances Brawn And Balladry

On the 1971 album, he found the balance that would characterize the remainder of his career.

Bobby Womack was already an established talent by the time he embarked on his solo career in the late 1960s – having sang lead with his siblings’ gospel-turned-R&B quintet The Valentinos, and penned songs covered to huge success by the Rolling Stones (“It’s All Over Now”) and Wilson Pickett (“I’m in Love”). Possessed with a gruff baritone that blasted the polish off every syllable in its path, he could also sweetly unleash whoa-oa-oh’s in the crooning style of his mentor, Sam Cooke. The former tended to dominate his early individual recordings. However, with 1971’s Communication – his first in a series of winning efforts for United Artists – Womack found the balance of brawn and balladry that would characterize the remainder of his storied career.

Listen to Bobby Womack’s Communicator now.

More than simply a gifted vocalist and guitarist, Womack was above all a storyteller whose live shows featured extended monologues delivered as though from the pulpit (hence his nickname, “The Preacher”). On the album’s soul stirring centerpiece – an epic, 9-and-a-half-minute cover of the Carpenters’ pop hit “Close to You” – he delivers one such sermon: a confessional about his struggles within the music industry centered around the loaded term, commercial. “‘I like you, and I ain’t saying that you can’t sing,’” he recalls a particularly patronizing record exec telling him, “‘but you’re not commercial.’” To which he counters, “I can feel down in my heart, I don’t care what it is: if I can get into it, it’s commercial enough for me.” Whatever his intro leaves unsaid, Womack’s charismatic performance completes, transforming the Bacharach/David-composed tune into a soulful testimonial that set the baseline for interpretations by everyone from Gwen Guthrie to Frank Ocean.

The moral of Womack’s “Close to You” yarn – “I didn’t change my style because I still had the same heart” – is in evidence throughout the rest of Communication. He convincingly covers additional soft rock hits by Ray Stevens (“Everything Is Beautiful”) and James Taylor (“Fire and Rain”), recaptures the romantic lilt of his early ’60s beginnings (“Come L’Amore”), and revisits his church roots (“Yield Not to Temptation”). As new wrinkles go, the title cut’s pleas for better global understanding lean on a propulsive soul/funk rhythm abetted by the pulse of a Rhythm King drum machine on loan from Sly Stone – at whose Bel Air home studio much of Communication was recorded (as was Sly’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On, on which Womack also sang and played).

Like his close friend, Womack’s best material explores dichotomies. But rather than dabble in opaqueness a la Sly, Bobby can’t help but wear his emotions on his sleeve. “(If You Don’t Want My Love) Give It Back” is quintessential Womackian straight talk. And with “That’s the Way I Feel About ’Cha” he crafts his first sublime single of the ’70s. Over a plaintive guitar hook that practically weeps, Bobby quells his girl’s doubts about his intentions in terms both cocky (“You’re pushing my love a little bit too far… I don’t think you know how blessed you are”) and compassionate (“I know you been hurt and so has many others too / But that’s a sacrifice that life puts you through”). It’s this tension between bitter and sweet that helps his message land – something every great communicator understands.