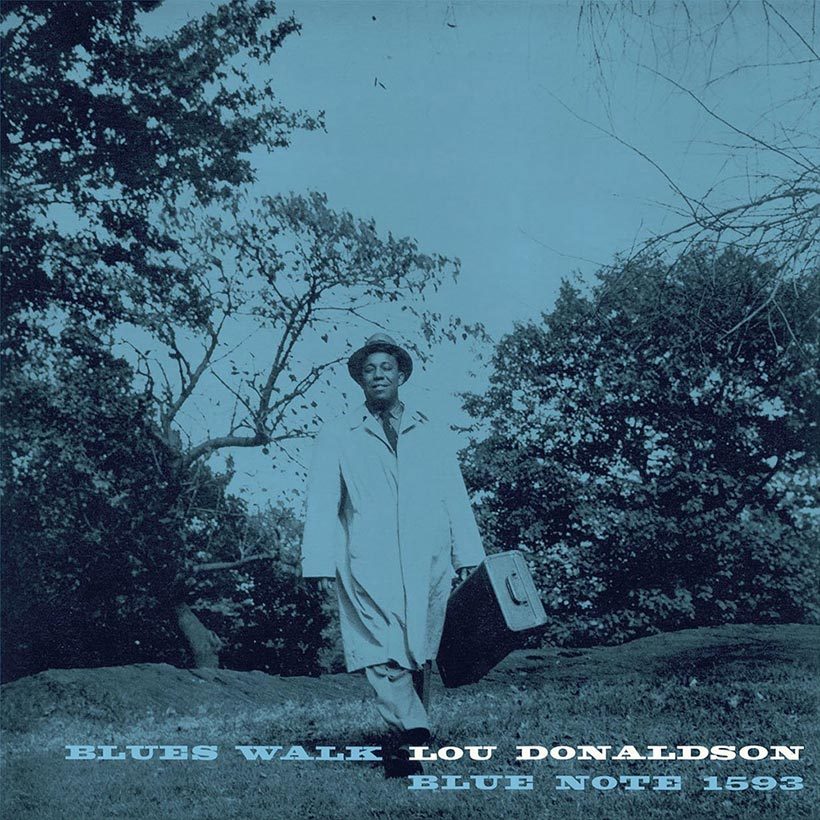

‘Blues Walk’: How Lou Donaldson Strode Towards Soul Jazz

‘Blues Walk’ helped to kick-start the soul-jazz movement of the 60s and remains the go-to album in saxophonist Lou Donaldson’s canon.

On July 28, 1958, a 31-year-old alto saxophonist called Lou Donaldson went into Van Gelder Studio, in New Jersey, to record Blues Walk, a six-track LP released by Blue Note Records that many now regard as his greatest album and definitive musical statement.

Originally from Baden, a small rural town in North Carolina, Donaldson was born into a musical family – his mother was a music teacher – and started playing clarinet when he was nine. As a teenager, he went to college in Greensboro, and was then drafted into the US Navy in 1944, where he played clarinet in a military band. “When I heard Charlie Parker, the clarinet was gone,” Donaldson told an interviewer in 2012, recalling the time when, hooked on the sound of bebop, he took up the alto saxophone, the instrument that he is most associated with. Though Donaldson was heavily influenced by Parker at first, he soon developed his own style.

On Dizzy Gillespie’s advice, Donaldson moved to New York in 1950 and quickly made his mark on the Big Apple jazz scene, where bebop was the hip currency. Blue Note’s boss, Alfred Lion, heard Donaldson playing in a Harlem club and invited him to sit in on a Milt Jackson session.

It wasn’t long before the impressive young altoist was making his own records and, in the early 50s, he became an architect of hard bop, a more R&B-oriented offshoot of bebop, usually led by a band with two horns and driven by a swinging groove. Donaldson’s 1953 joint collaboration with virtuoso trumpeter Clifford Brown, for the Blue Note LP New Faces, New Sounds, offers one of the earliest examples of hard bop, though drummer Art Blakey’s landmark 1954 album, A Night At Birdland, which Donaldson also played on, is widely acknowledged as the first bona fide hard bop record.

By 1958, despite only being in his early 30s, Donaldson, who acquired the nickname “Sweet Poppa Lou,” was a well-established figure on the American modern jazz scene. Blues Walk was his eighth album for Blue Note and was the follow-up to 1957’s Lou Takes Off, an LP on which the saxophonist started peppering his music with a more pronounced R&B feel, presaging a style that would be dubbed “soul jazz.”

For this particular session, Donaldson brought together pianist Herman Foster – a blind musician from Philadelphia who had played on a couple of previous sessions with the saxophonist – along with bassist and fellow Pennsylvanian “Peck” Morrison and drummer Dave Bailey (both Morrison and Bailey had previously played with “cool school” saxophonist Gerry Mulligan). To add extra spice and rhythmic heat, Latin percussion specialist Ray Barretto was brought in on congas.

With its strolling, easy-swinging gait, strong backbeat, and piquant blues inflections, the album’s opening title cut quickly became Lou Donaldson’s signature tune. Its main melodic theme, denoted by bittersweet cadences, is enunciated by Donaldson before he showcases his improv skills with an inventive solo. Foster takes the second solo and then there’s a drum and conga dialogue between Bailey and Barretta before Donaldson’s sax re-enters.

As its title suggests, “Move” is much livelier. Performed at breakneck speed, it’s Donaldson’s take on a bebop staple by jazz drummer Denzil Best. The tune was famously recorded by Miles Davis (a slightly slower tempo) on his 1949 session for Capitol Records, later released as an LP called Birth Of The Cool.

“The Masquerade Is Over,” a song written by Herb Magidson and Allie Wrubel, was first recorded by the Larry Clinton orchestra in 1939 and later, in the 50s, became a popular ballad with jazz singers (among those who recorded it were Sarah Vaughan, Helen Merrill, Abbey Lincoln, and Jimmy Scott). Donaldson reconfigures it as a breezy groove, though he plays the caressing main melody with a gilded lyricism.

Propelled by the perpetual motion of “Peck” Morrison’s walking bass, “Play Ray” is a simmering self-penned Donaldson number that’s steeped in the blues. Its title is presumably a reference to Ray Barretto, who takes a conga solo during the tune.

On the slow ballad “Autumn Nocturne,” Donaldson demonstrates his sensitivity with a sublime interpretation of a jazz standard penned by Joseph Myrow and Kim Gannon (those who had recorded it before Donaldson include the Claude Thornhill Orchestra, trumpeter Art Farmer and flautist Herbie Mann).

Blues Walk closes on a euphoric high with the sprightly “Callin’ All Cats,” a blues-infused Donaldson-penned swinger that oozes energy and effervescence.

Lou Donaldson recorded for Blue Note up until 1974, but he was never able to make another album as perfect as Blues Walk. A truly landmark session, it showed him stepping out of Charlie Parker’s shadow and finding his own, unique voice on the alto saxophone. But that wasn’t all. Blues Walk also helped to kick-start the soul-jazz movement of the early 60s. Decades later, it remains the go-to album of the saxophonist’s canon.

Geoffrey Whitlock

February 8, 2019 at 3:20 pm

The melody of Blues Walk was the very first jazz line I took down when I was a teenager beginning to learn clarinet, around mid-sixties. I wrote it out and proudly presented it to my teacher who had introduced me to Lou Donaldson’s playing on the Live at Birdland albums with Art Blakey and Clifford Brown. Like Lou, I discarded the clarinet in favour of a sax… though I never attained to anything like Lou’s level of playing…. at all.

The Blues Walk album is still one of my favourite albums; it sparkles. It also has by far the most beautiful reading of Autumn Nocturne I’ve ever heard. The whole album always puts me back in touch with how I felt when I was first discovering jazz.