Billy Strayhorn’s Lush Life Beyond Duke Ellington

The composer and arranger is best known for his collaborations with Duke Ellington, but his immense talent and artistry shine on their own.

Billy Strayhorn is undoubtedly one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. While he may not be a household name, that in no way diminishes his tremendous impact.

Largely known for his nearly three-decade-long collaboration with Duke Ellington, much like Duke, Strayhorn exuded natural sophistication and style. This coupled with his talent for crafting some of the most beautiful songs should have easily positioned him alongside many of his white counterparts (Gershwin, Mercer, Berlin). Not only did the racism not deter him, he continued to flourish, living a full life without apology or compromise at a time when it simply was not a choice for an openly gay Black man. Strayhorn drew inspiration from his own life experiences, giving us compositions that were both deeply personal and ubiquitous all at once.

“Lush Life” is a prime example. I’d like to think that I always admired the song itself, full of vivid contrast (“Life is lonely again, / And only last year everything seemed so sure.”). However, I could never fully appreciate it until I finally experienced true love and heartache firsthand. As I learned more about the song’s origin — how he was a teenager when he started writing it in 1933, then living in one of the poorest sections of Pittsburgh — my admiration only grew over the years.

Written in D-flat major, the song was initially titled “Life is Lonely.” Strayhorn’s lyrics are juxtaposed against a backdrop of complex chord modulations for a love song, oscillating between ethereal and stark reality. Reportedly inspired by personal experience of unrequited love, with “Lush Life,” Strayhorn strikes a balance of vulnerability with style and sophistication, well beyond his years. Much like the Duke himself, Strayhorn would become a master at encapsulating life’s mundane and ordinary moments, later turning them into something worldly and timeless.

William Thomas Strayhorn was born in Dayton, Ohio, on November 29, 1915. His parents, James and Lillian, struggled to provide for their family, as the three of them once lived in a one-room boardinghouse on Norwood Avenue. With just an eighth-grade education, James ultimately found work as a wire-cutter and gas-maker. Strayhorn and his family later moved to Homewood, which was an integrated and diverse community in Pittsburgh. However, to shield him from his father’s drunken bouts, his mother Lillian would often send Strayhorn to stay at his grandparents’ home in Hillsborough, NC.

The history of his family in Hillsborough dates back nearly two centuries, as his great-grandmother worked as a cook for Confederate general Robert E. Lee. However, his grandmother Elizabeth Craig Strayhorn helped cultivate Strayhorn’s gift for music — from playing old records on her Victrola to eventually growing tall enough to reach the piano’s keys and playing hymns for the whole family.

Breaking the color barrier

Working odd jobs as a soda jerk and drugstore delivery boy by day to buy his first piano, Strayhorn took piano lessons from instructor Charlotte Enty Caitlin. He would often show up late for work because he spent most of his days playing the piano. He studied at Westinghouse High School, which many jazz artists attended, including Mary Lou Williams, Erroll Garner, and Ahmad Jamal. His father later enrolled Strayhorn in the Pittsburgh Musical Institute (PMI).

One of the top music schools in the nation, PMI was also one of the more progressive ones, breaking color barriers forced by Jim Crow-era laws to admit students of color, producing luminaries like Strayhorn and Jamal. While studying classical music, Strayhorn also formed a trio that played daily at a local radio station, regularly composed songs, even wrote the music and lyrics for a musical called Fantastic Rhythm in 1935, at just 19. The show featured the now-standard “My Little Brown Book.” While musical genius knew no bounds for Strayhorn, he had to face head-on the brutal reality of what life could be for an artist of color – especially as an openly gay Black man living in America.

For Strayhorn, there was no precedent for he pretty much lived just as he worked – on his own terms. It certainly did not affect his working relationship with Ellington. Many assumed that he was romantically linked with Lena Horne since their initial meeting in 1941, but they were, in fact, just very good friends. Leading a “double-life,” especially in that era of blatant discrimination and homophobia, would have been completely valid and understandable. For Strayhorn, however, that just was not an option.

Shut out from the classical music world, which was [and still remains] predominantly white, instead of shrinking, Strayhorn soon transitioned over into the world of jazz. Alongside fellow students drummer Mickey Scrima and guitarist Bill Esch, Strayhorn became part of a combo known as the Mad Hatters, who performed all over Pittsburgh. Two years later, he soon began writing arrangements for local acts like Buddy Malone’s Pittsburgh dance band.

A collaborative dynamic was born

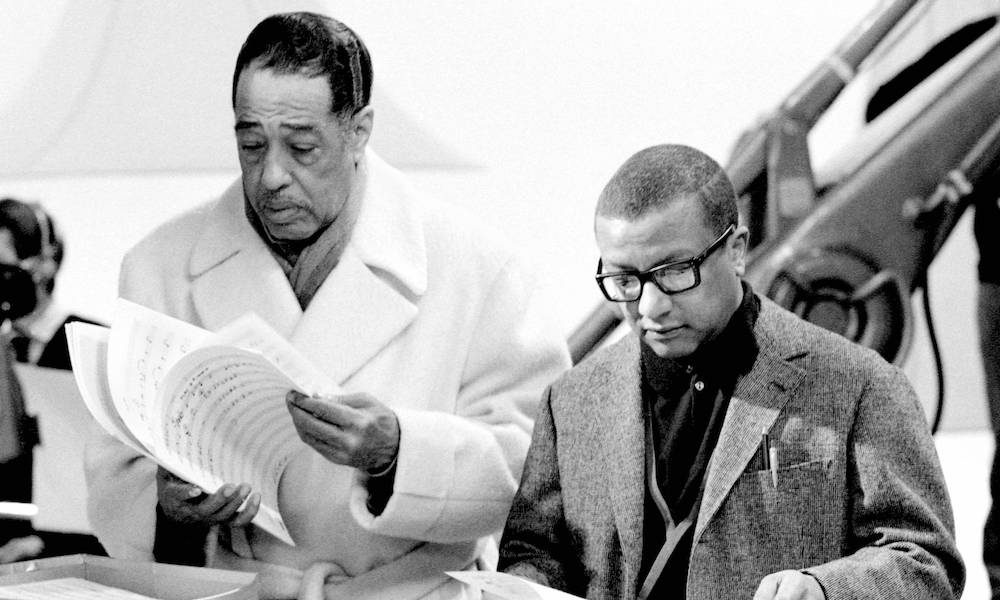

In 1938, Billy Strayhorn was introduced to his lifelong collaborator and creative partner, Duke Ellington, who asked the aspiring musician to play for him after the show. So, Strayhorn began to play “Sophisticated Lady,” at first, mimicking exactly how Duke performed it during his set. Then, he said, “Well, this is the way I would play it.” And so, their collaborative dynamic was born – taking what Ellington started and building off of that.

Great Times! highlights just some of Strayhorn’s 1,000+ songs, most of which were primarily for Ellington. Originally released in 1950 as Piano Duets, it features duet performances between Ellington and Strayhorn with some of their best-known collaborations, including the uber-classic “Take the ‘A’ Train,” which was the signature tune for the Duke Ellington Orchestra. After Ellington hired Strayhorn, he paid him money to travel from Pittsburgh to New York City. His written directions for Strayhorn to get to his house by subway, which began with “Take the A train,” would soon become the lyrics that Strayhorn reportedly wrote en route to Ellington’s home.

Capturing the vitality of the Black experience

We are all most likely familiar with the 1952 version, which features vocalist Betty Roche and a cacophony of horns inspired by Fletcher Henderson’s arrangements for trumpets, reeds, and trombones, coupled with Ellington’s prowess at writing for a musician within his band. Strayhorn and Ellington together not only captured the vitality of 1940s Harlem in its prime but, musically, it evoked a promise for upward mobility and progress for Black populations all over.

On Great Times!, songs like “Take the A train” get stripped bare. Backed only by a quintet that features Oscar Pettiford on cello and drummer Jo Jones, with Strayhorn on the celeste and pianist Ellington, you not only appreciate the song’s melodic structure, but it offers perhaps a glimpse at how rather seamlessly they worked in unison. Ellington once said that “Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine.”

While jazz has undoubtedly produced some of the world’s greatest voices, it has also been confining for artists like Ellington and Strayhorn, whose contributions go well and beyond the genre. Erroneously passed over for the Pulitzer Prize in 1965, Ellington reportedly said to Nat Hentoff that most Americans “still take it for granted that European music – classical music, if you will – is the only really respectable kind…jazz [is] like the kind of man you wouldn’t want your daughter to associate with.”

One example of this slight is evident with their film score for Anatomy of a Murder. Released as the film’s soundtrack on Columbia Records in 1959, Strayhorn and Ellington composed such evocative yet non-diegetic suites like “Such Sweet Thunder” and “The Far East Suite,” and the sultry tune “Flirtibird,” which famously features suggestive trills from alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges. A few years later, they would reunite to record Johnny Hodges with Billy Strayhorn and the Orchestra in 1962. While the soundtrack won three Grammy awards and is now regarded as groundbreaking for film scorers contributed by Black musicians, Anatomy of a Murder did not garner an Oscar nomination for Best Score the following year.

Strayhorn the activist

Though Strayhorn’s life alone was a testimony of courage and strength when Blacks had few options for a good life, he was a staunch supporter of civil rights. A good friend to Martin Luther King, Jr., Strayhorn arranged and conducted “King Fit the Battle of Alabama” for the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1963, part of the historical revue and album titled My People.

Billy Strayhorn left an indelible mark on those who encountered him. Lena Horne considered him to be the love of her life, even falsely believed to be at his side at the time of his death from esophageal cancer in 1967 (she was, in fact, in Europe at the time on tour). He found a modicum of love over the years through several partners, including musician Aaron Bridgers, with whom he lived for eight years until he moved to Paris in 1947, and Bill Grove, who was in fact with him at his deathbed. However, Strayhorn’s greatest and most consistent love affair was with song.

While in the hospital, Strayhorn handed over his final composition to Ellington entitled “Blood Count,” the third track to Ellington’s memorial album for Strayhorn, And His Mother Called Him Bill, which was recorded several months after Strayhorn’s death. The final number is a spontaneous piano solo of Strayhorn’s “Lotus Blossom.” As you hear the band packing up at the end of the recording session, Ellington continues playing for his longtime friend from Pittsburgh.